Moscow is full of Soviet-era institutions built on once-sacred ground. While passers-by might have little reason to notice these buildings, the Russian Orthodox Church is, in many cases, fighting legal battles to evict long-time tenants and claim valuable, centrally located real estate that was once appropriated by Soviet authorities.

Just this year, the Church has made claims upon the offices of the literary journal Novy Mir, which occupy part of the last surviving building of the demolished Strastnoi Monastery; a chapel and a morgue belonging to the Moscow City Scientific and Practical Center for Tuberculosis Control, which occupies a 19th-century almshouse (the morgue, a former church, is in a separate building); and the Andrei Rublyov Museum of Ancient Russian Art, which occupies the mediaeval Andronikov Monastery.

The Church is making its claims under Federal Law No. 327, “On the Transfer to Religious Organizations of Property of Religious Purpose in State or Municipal Ownership.”

Russia passed the law in 2010 as part of an ongoing effort—dating back to the 1990s—to reverse the legacy of the Bolsheviks’ nationalization of Church property following the Russian Revolution of 1917.

The anti-religious ethos of the late Soviet state left many famous Moscow churches with bizarre and traumatic histories of forced closure, desacralization, and re-use.

The Church of the Nativity at Putinki, for example, was once used for training circus animals; the Church of St. Nicholas the Miracleworker was half-destroyed, rebuilt with a Stalinist facade, and eventually used by the animation studio Soyuzmultfilm; St. Clement’s Church—one of Moscow’s largest—was turned into a book depository for the Lenin Library.

In the course of contemporary property battles, those who are keen to see real estate redeveloped by the Church sometimes invoke unhappy memories of the Soviet-era anti-religious project that was once championed by official propaganda organizations like the League of the Militant Godless and the Knowledge Society, and by illustrated anti-religious magazines like “Godless” and “Science and Religion.” The Church makes these accusations despite the lack of much obvious sympathy or nostalgia for Soviet atheism in modern-day Russia.

The specter of Soviet atheism haunted Russian politics this spring, for example, when protestors in Yekaterinburg demonstrated against the construction of a new church—and associated commercial ventures—in and around a popular park. While the dispute was largely about the accountability of local officials, Church representatives were quick to link the protestors with atheism, since the new building was intended to be a replica of St. Catherine’s Church, which communist authorities had destroyed in 1930.

Vakhtang Kipshidze, an Orthodox Church spokesman, said that the protests “could only have been organized by people with anti-religious motives.” Patriarch Kirill said, “Our people who have gone through years of atheism know that without God, nothing happens.” Even President Vladimir Putin inquired as to whether the protestors might have been “godless” before directing that public opinion be considered.

The project in Yekaterinburg, which has since gone back to the drawing board, had a precedent in Moscow’s controversial Cathedral of Christ the Savior, a 1990s replica of a grand 19th-century cathedral that Stalin’s henchmen demolished in 1931.

The replica building that now stands by the Moscow River—where it replaced the Khrushchev-era swimming pool called “Moscow”—is a commercial entity containing an auto service station, underground parking, a laundry, and even a jewelry dealership.

These commercial activities were among the reasons the feminist performance group Pussy Riot staged their “punk prayer” in the cathedral in 2012, before being arrested and charged with “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.”

Pussy Riot’s stunt was—consciously or otherwise—the most Bolshevistic challenge levelled at the Church since the end of Soviet rule, insofar as it evoked two Soviet propaganda themes: the Church’s oppression of women, and the greed of the clergy.

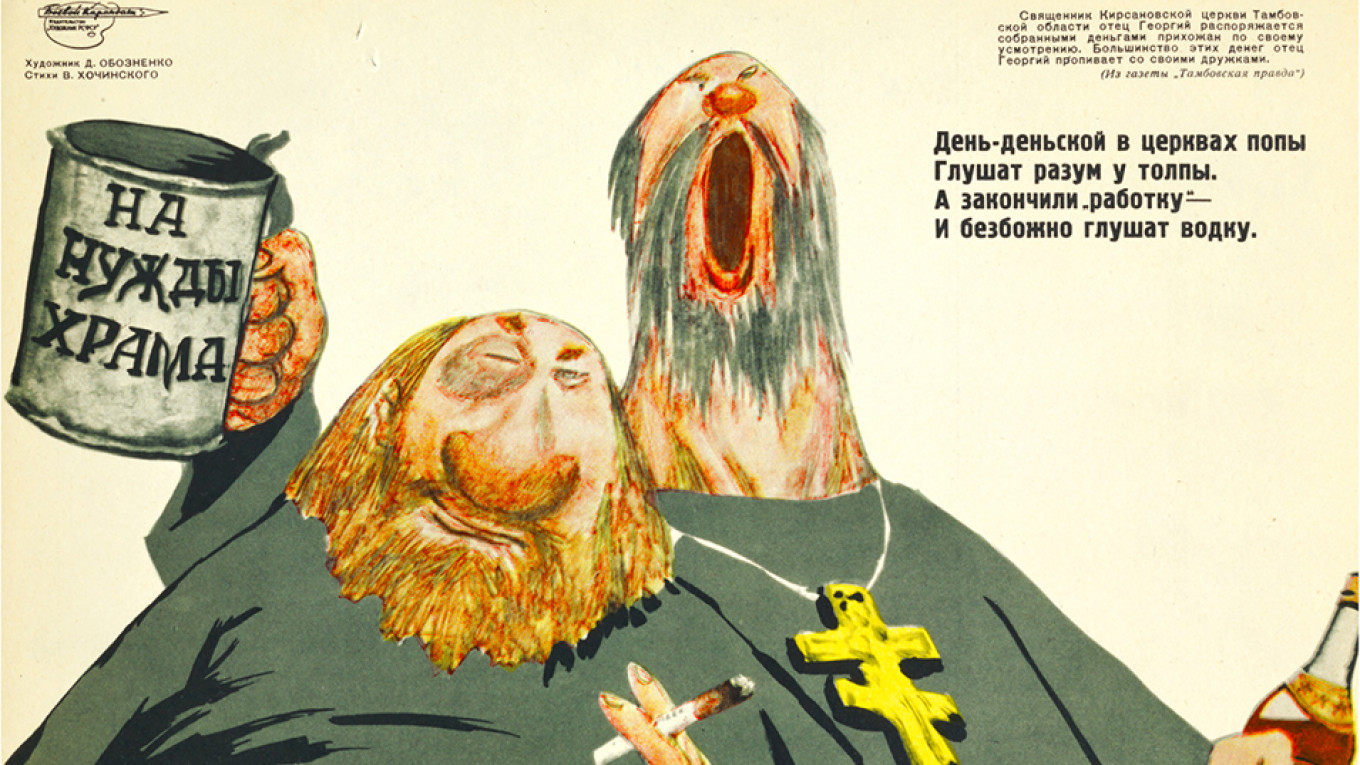

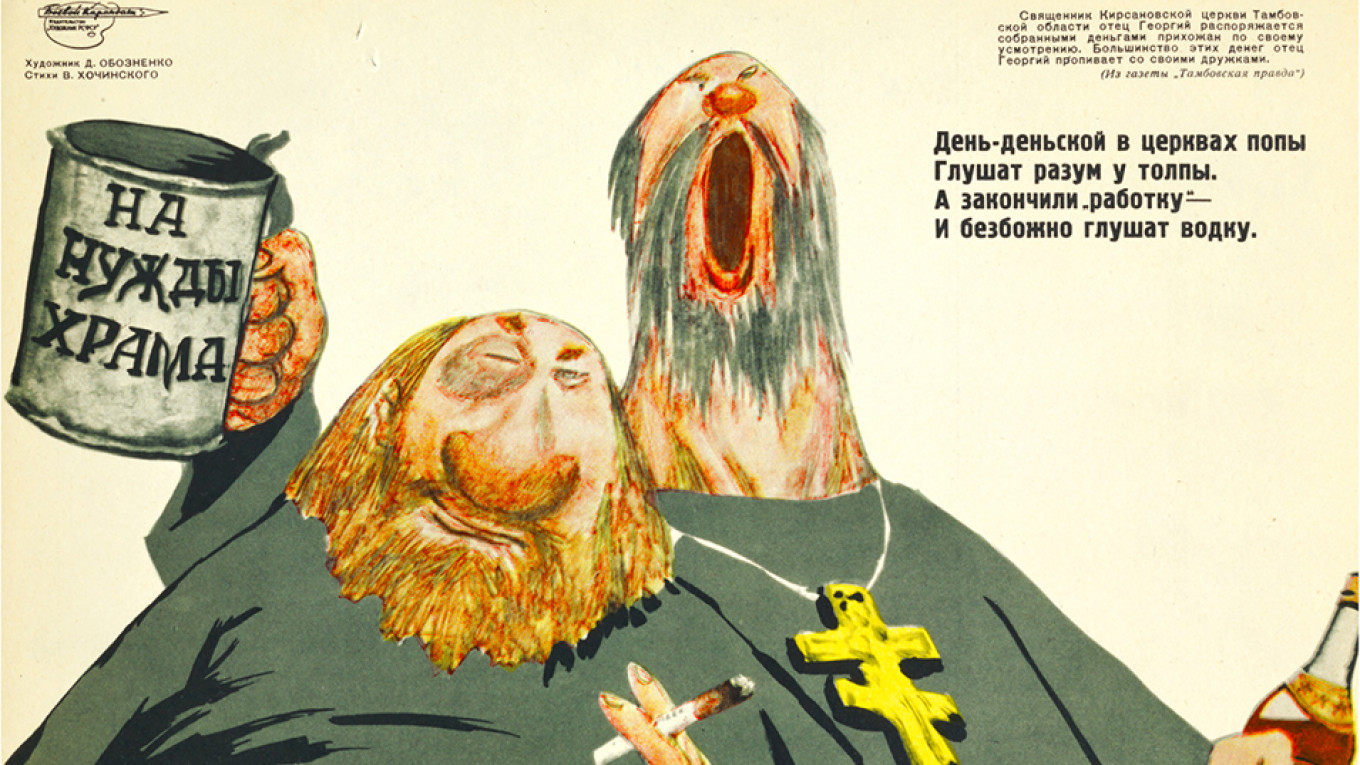

In Soviet political cartoons, illustrators frequently showed Russian clergy defrauding parishioners, ringing church bells till coins rained down, and, in one example, even milking a church like a cow’s udder for money. Others showed village priests squandering their gains on booze and lechery, and foreign priests taking money from the CIA in exchange for their “lies” about religious persecution in the USSR.

The mass political repression the clergy faced under Soviet rule, along with the widespread vandalism authorities visited on its historic buildings, have brought the institution much sympathy. Even Novy Mir editor Andrei Vasilevsky, faced with losing his offices, told Novaya Gazeta that the law on Church property was “historically […] a very good and correct law”—despite his objections pertaining to his own case.

And yet, the type of claims the Church is now making—upon a tuberculosis clinic or a popular museum that carefully preserved Russia’s religious heritage from the late Stalin era to the present day—suggest its leaders believe they have sympathy to burn.

To the extent that Muscovites’ sympathies begin to wane, it will likely not be because they are, as American Cold War propagandists once had it, “godless communists”.

Leave a Reply