The AZ Museum of non-conformist art is celebrating its fifth anniversary with an exhibition dedicated to George Costakis, who was, without exaggeration, the savior of the early Russian avant-garde and post-war non-conformist art and artists. Called “Costakis’ Choice,” the show leads visitors through the life of this great collector, which is to say through the art he chose to collect — from icons and folk toys to 20th century Russian art.

Costakis’ Gift

George Costakis was born in Russia into a Greek family in 1913. Throughout his life he kept his Greek passport, which allowed him to work at the Greek and Canadian embassies — and provided him with diplomatic immunity from the strict laws governing the purchase of works of art.

Costakis did not have an education in the arts. He was, however, a born collector.

He began on the 1920s by buying porcelain and 16th and 17th century Dutch paintings — sold by former aristocrats and wealthy merchants in commission shops — before amassing a fine collection of icons and religious arts. A little later he bought an entire collection of Russian toys that had been gathered by the actor Nikolai Tsereteli.

And then he was hit by the lightning bolt of the Russian avant-garde art.

By the post-war years the only official style of art permitted in the Soviet Union was Socialist Realism. Works by the pre- and post-revolutionary avant-garde were banished from museums; avant-garde artists had emigrated, died, or gone underground, their art hidden away or sometimes destroyed.

But in 1946 among the stacks of paintings of peasants and workers, Costakis saw a painting by Olga Rozanova called “Green Stripe.” Later the family would quibble over the details — was it in someone’s home or in an antique shop? — but in any case, it changed his life. Not long before he died he said in an interview, “I brought it home to my flat, with the silver, the carpets and so forth, and I realized that I had lived until then with closed windows.”

Like a man possessed, Costakis searched out avant-garde art in antique shops, commission shops, in artists’ studios and apartments, and sometimes with the relatives of the artists’ heirs. In the country house of a descendent of Liubov Popova, he found one of her priceless paintings used to plug up a hole in the wooden fence around the property.

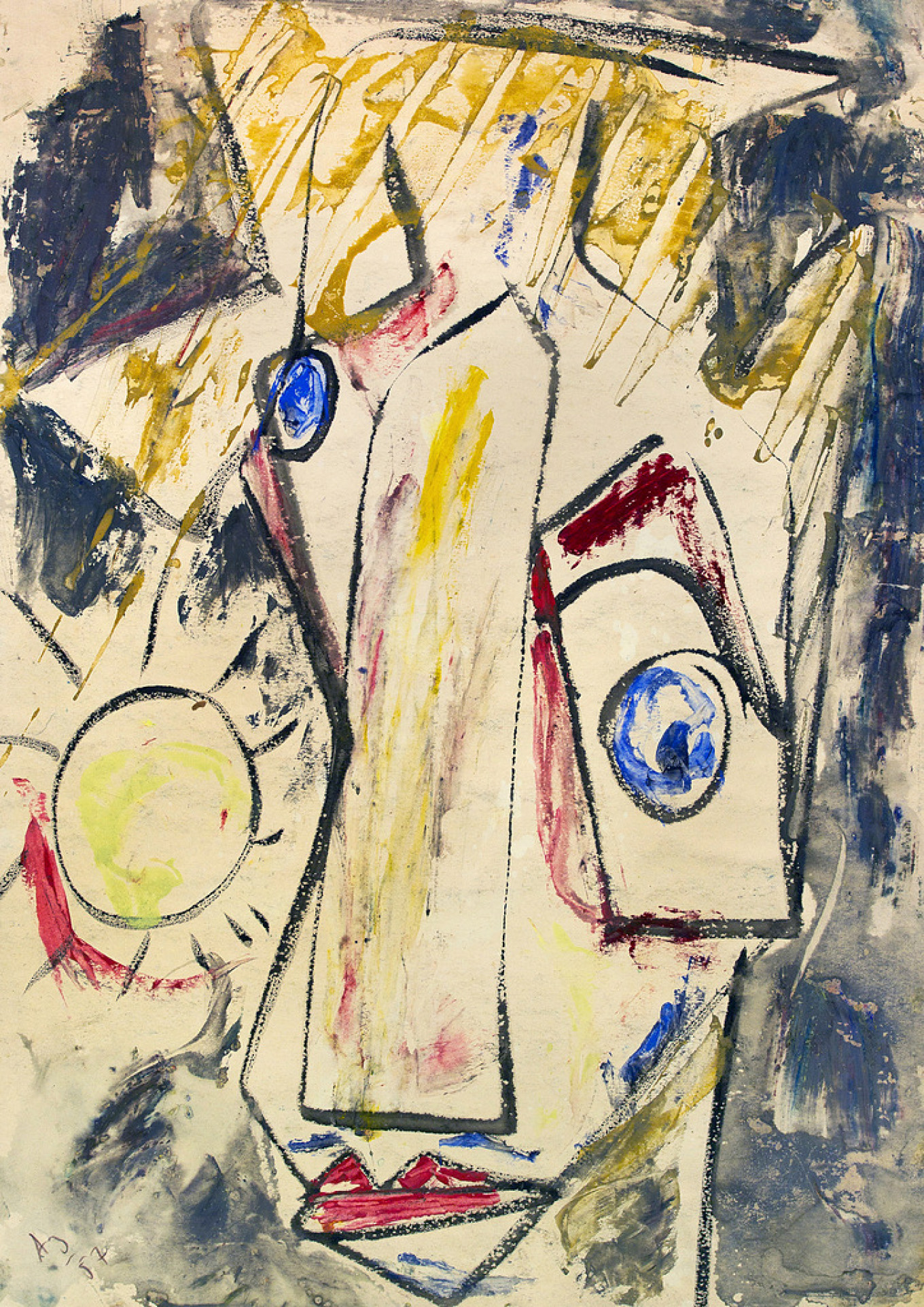

In 1954 Costakis met Anatoly Zverev, which was another turning point in his life and collection. Zverev, whom Costakis considered a genius, became almost a member of the Costakis family. Costakis bought hundreds of his works as well as a few paintings a year from the dozen or so other non-conformist artists he befriended. His collection expanded.

In 1965 Costakis used his privilege of Greek citizenship to fly to Paris, where he met Marc Chagall and the giants of the first avant-garde, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. In Moscow, his house — renowned for its hospitality — became a kind of private showroom of the early avant-garde and contemporary unofficial art. Diplomats, art specialists, museum curators, and even politicians like U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy flocked to the apartment on Prospekt Vernadskogo to see the art that the Soviet authorities scorned.

The situation, however, began to worsen. By 1976 there had been thefts and a fire at the Costakis dacha. The family decided that it was time to leave.

Costakis wanted to give his collection to the Soviet state for a museum. But after years of negotiation, there was still no firm commitment. In the end, Costakis made a deal with the Soviet government: he donated the icons and religious art to the Rublyov Museum, the folk art and toy collection to the Ministry of Culture (later made part of the Tsaritsyno Museum Reserve collection), and 80 percent of his avant-garde and non-conformist works to the State Tretyakov Gallery. In return, he was allowed to take out 1200 works, which became the basis of the Thessaloniki State Museum of Modern Art in Greece.

George Costakis emigrated with his family to Greece in 1977 and died in 1990 at the age of 77. In 2013 his daughter Alika gave more than 600 works from the family collection to the AZ Museum.

Costakis’ Choice

The show at the AZ Museum takes visitors through Costakis’ life, starting on the first floor with a biographical film called “Costakis’ Gift” (in Russian) by Yelena Lobachevskaya and interactive walls of photographs and information about his life and work. In the corner are two small but exquisite exhibits of Costakis’ earlier collections: three icons dating back to the 16th century and toy figures that were part of Nikolai Tsereteli’s collection.

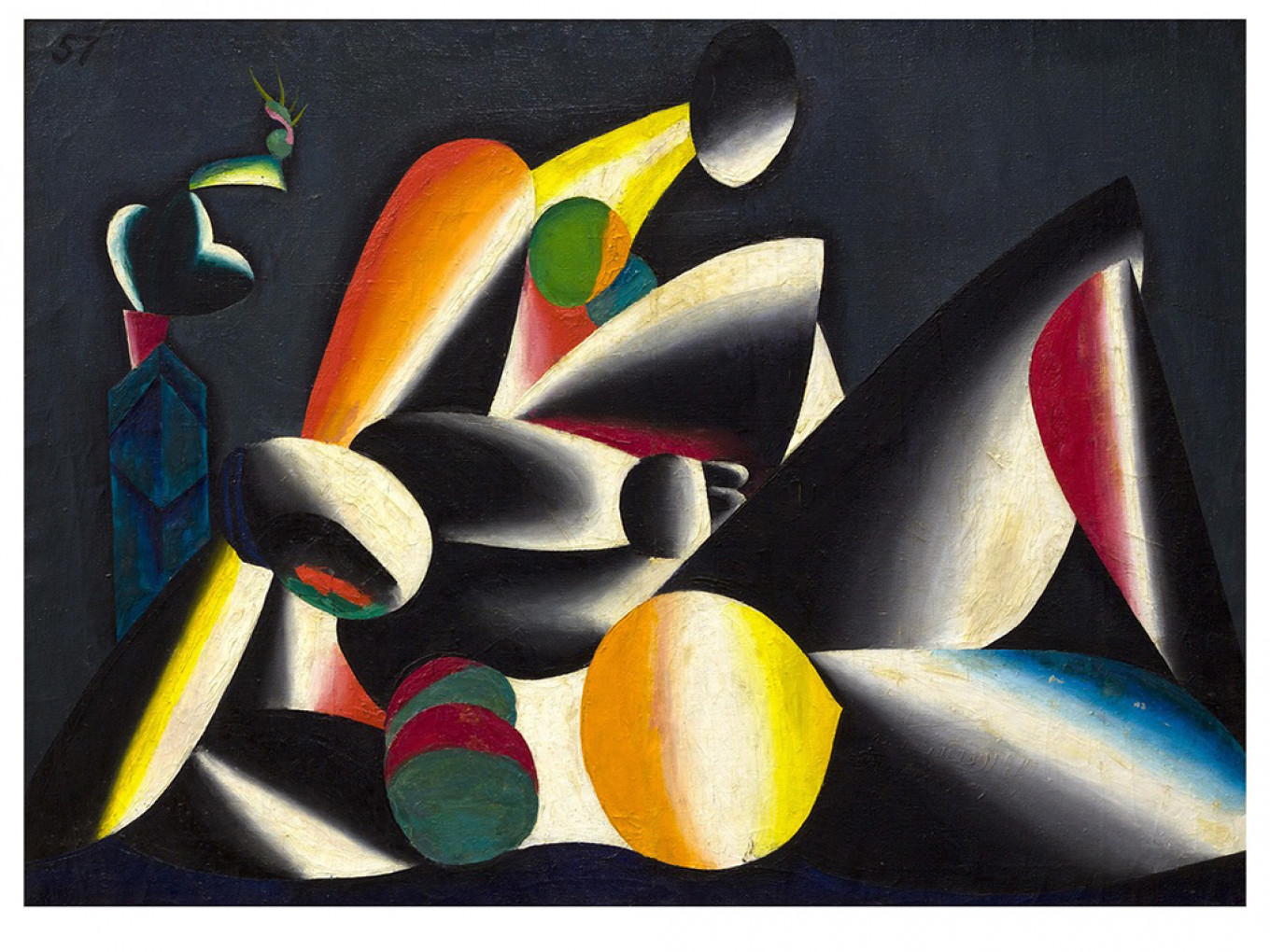

The second floor is dedicated to the early avant-garde: six masterpieces originally owned by Costakis on loan from the State Tretyakov Gallery, including one from his favorite painter, Liubov Popova, and a magnificent swirl of color and motion called “Red Square” painted by Wassily Kandinsky in 1916.

The third floor takes visitors ahead in time to the next generation, the non-conformist artists of the post-war period — what the AZ Museum calls the artists of the “Soviet Renaissance.” These were artists working in wildly different styles, united only by the fact that they did not conform to Soviet artistic dictates. You can see some of the best works by Francisco Infante, Anatoly Zverev, Vladimir Yakovlev, Dmitry Krasnopevtsev and many others.

There is one more turn to this generational spiral of art. On the second floor Platon Infante, the son of Fransisco Infante, has created an homage to the avant-garde and non-conformist works — a curved media installation that holds the avant-garde masterpieces across from it in a loose embrace of music and images that dance about the screen, disassemble, and recombine to form paintings. On the third floor, Infante has riffed off the set of 24 cubes with photographs of non-conformist artists that was done by photographer Igor Palmin for Costakis’ 40th wedding anniversary.

With this, the exhibition continues, as it were, with an artist working in a new medium in the third generation of art — a generation that could not have come to be without George Costakis, the man who saved 20th century Russian art.

Below: Fragment of Platon Infante’s Media Installation playing with the painting “Asters” by Aristarkh Lentulov, 1913, now in the State Tretyakov Gallery.

Leave a Reply