If World War I radically transformed warfare and the experience of combat, it also changed the art commissioned to depict it.

When a squadron of artists was dispatched along with the troops for the first time to chronicle the American entry into the war a century ago, no longer would they stay home, rendering generals in heroic statues long after the fact.

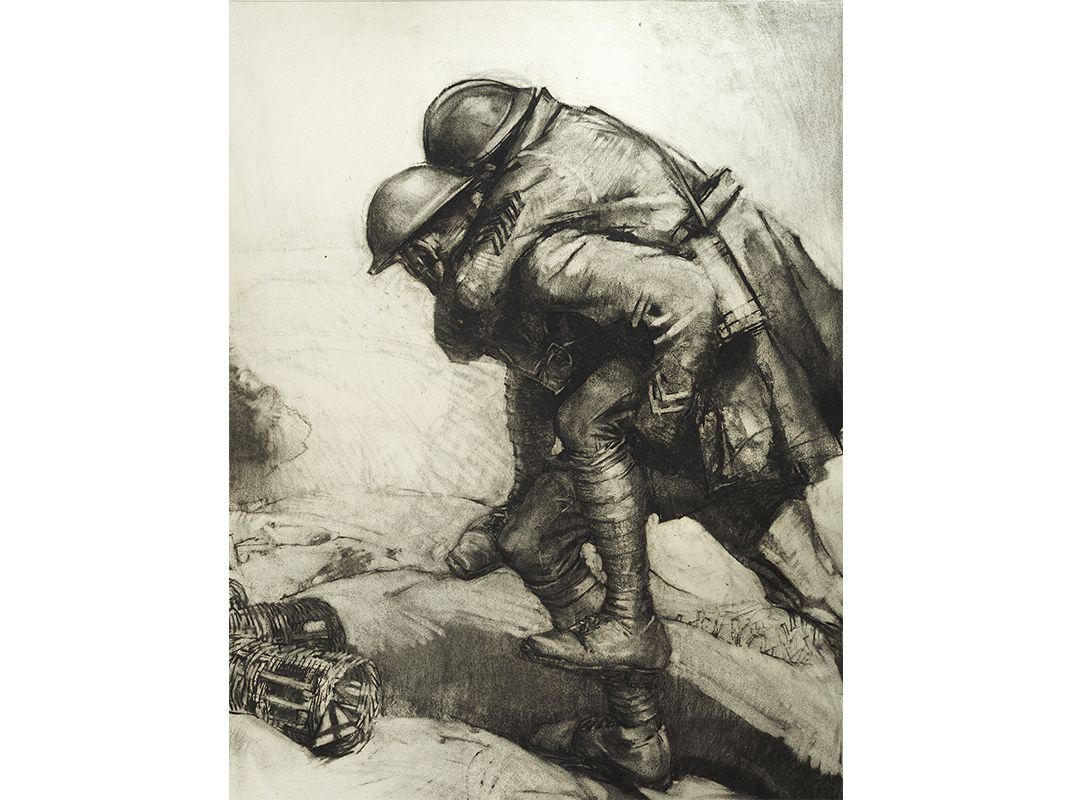

Instead, they depicted the lonely troops in real time, trudging to the next trench in the torn up countryside of an unfamiliar country.

These were the artists of the American Expeditionary Forces—eight professional illustrators commissioned as U.S. Army officers, embedded with the troops in France in early 1918. Some of the best of the work is being shown for the first time in 80 years as part of a two-pronged exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Entitled “Artist Soldiers: Artistic Expression in the First World War,” the show opened on the 100th anniversary of the U.S. declaring war on Germany.

Why the Air and Space museum? Well, airborne conflict was another first during the Great War. (Also, the Smithsonian’s other museums happen to be packed with a plethora of other World War I centennial exhibitions).

In addition to the more than 50 works by the professional AEF illustrators and artists on display—about a tenth of the holdings are from the collections of the National Museum of American History—the Air and Space exhibition also shows more than two dozen large format contemporary photographs of unusual carvings by soldiers left in large underground bunkers beneath the French countryside.

The series of images by photographer Jeff Gusky shows the wide variety of little known work carved by soldiers to mark their stay or while away time before battle. They include chiseled portraits, patriotic shields, religious icons and the usual array of girlie shots. They show an artistic expression different in skill than the professional embeds, but whose work is often just as evocative of their endeavor.

They were done as bombs exploded nearby, which was also the working conditions of the professionals, selected by a committee headed by Charles Dana Gibson, the famous illustrator behind the Gibson Girl drawings of the day.

“These were really the first true combat artists,” says Peter Jakab, chief curator at the Air and Space Museum who put the exhibition together. “This was the first time you had artists depicting war in the moment, giving a realistic impression of things, not just the heroic depiction of battle after the fact.”

Doughboys trudge by the smoke, fog and barbed wire in the oil on canvas On the Wire, by Harvey Thomas Dunn, who was one of the best known of the artists. A device he used on the field, in which he could make drawings on a scroll, is included as among the artifacts.

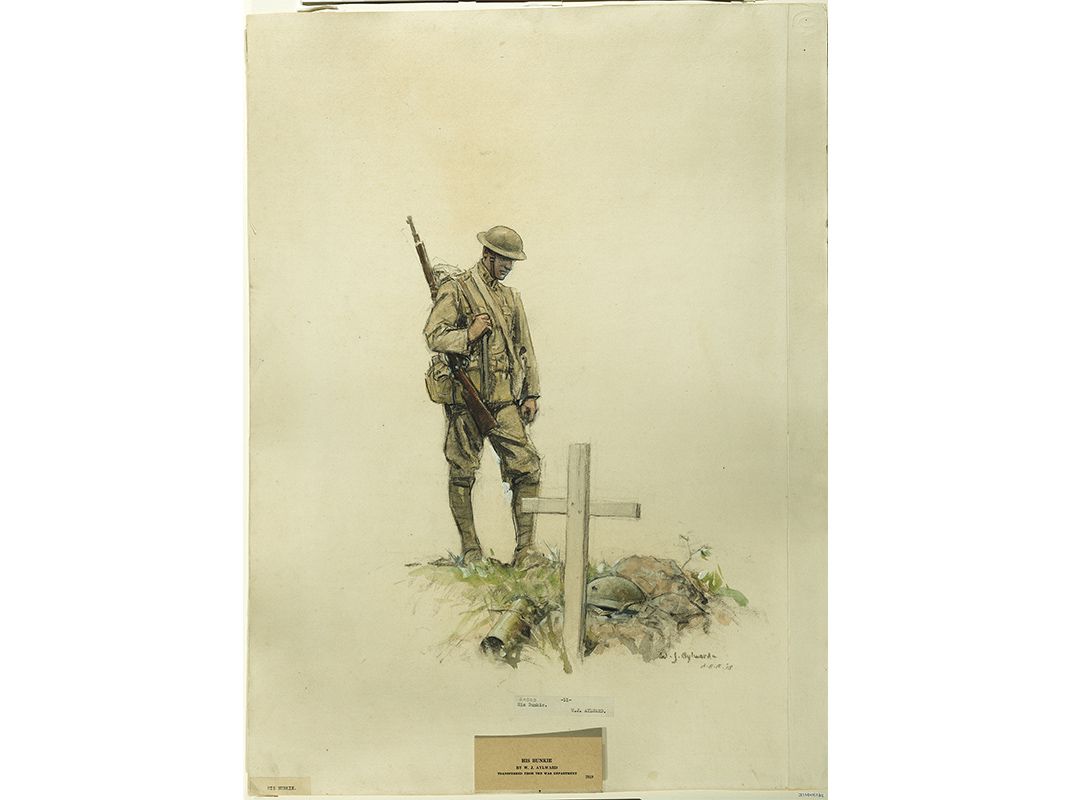

The work by Dunn and the rest of the artists— William James Aylward, Walter Jack Duncan, George Matthews Harding, Wallace Morgan, Ernest Clifford Peixotto, J. Andre Smith and Harry Everett Townsend—depicted many aspects of the first industrialized, highly mechanized war, from the ships and heavy artillery to gas masks and field telephones. Examples of the latter two objects are depicted in the show as well.

And an empty wheelchair from the period stands amid the work showing the human cost of the war.

“Great historical events happen because of individuals and individual stories,” Jakab says. “And I think the wheelchair is is a very powerful example of that.”

But in addition to the combat scenes, there are depictions of everyday life, starting with the months of planning and logistical build up. The artists, commissioned as U.S. Army officers, were with the Army Corps of Engineers as that extensive build-up began. Duncan’s work of pen and ink wash and charcoal on paper, Newly Arrived Troops Debarking at Brest, details the activity.

Aylward’s American Troops Supply Train places the activity amid the distinctive look of a French village.

Smith’s Band Concert at Neufchateau, Duncan’s Barber Shop and First Aid Station of the Red Cross at Essey and Morgan’s The Morning Washup, Neufmaison (the latter among horses) show familiar moments amid unfamiliar settings.

Smith’s A Cell in the Monastery at Rangeval and Dunn’s Off Duty show the interior life of the often dazed or exhausted-looking soldiers.

To these works, the show adds examples of unusual “trench art,” in which soldiers carved items out of spent shell casings and bullets. Also, there is a recent acquisition, the painted insignia of the 94th Aero Squadron, a “hat in the ring” symbol using Uncle Sam’s hat, from a flier who shot down three enemy aircraft and four observation balloons. His victories are depicted in iron crosses notched inside the brim of the hat.

The relative crudeness of the insignia, compared with the educated hand of the illustrators, is matched with the amateur carvings inside vast, little known interior caves that are shown in Gusky’s monumental photos.

“What these are are stone quarries, which were used for centuries to build cathedrals and castles,” Jakab says. “During the war, they were like little underground cities. There was electricity down there and living quarters, all the necessary requirements to house soldiers. This was a refuge from the shelling and the battle.”

The underground sites were not well known, then or now.

“Some of these, you walk into a forest, and there’s a hole, and you go into a shaft 50 feet and this just opens up below,” Jakab says. “These are all on privately held farmlands in the Picardy regions of France where the battles were. The local landowners and farmers are vary protective of these spaces.”

The photographer, Gusky, got to know the owners and gained their trust enough to go down and get a look at them,” Jakab says. “The ceilings and walls were all stone, and the soldiers created these stone carvings.”

Among them is a portrait of Paul von Hindenburg, chief of the German General Staff during the war; symbols of various units, religious references, remembrances of fallen comrades and some ominous images, such as a skull with a gas mask on.

One self-portrait is signed in pencil. “His name was Archie Sweetman. He lived a very long life—he lived to be 100 years old. And in 1993, at the age of 98, he graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art,” Jakab says.

Another carving had a Massachusetts connection and portended to the future: It was the score of a major league baseball game between the Red Sox and the Yankees in 1918. Not only did it mark a rivalry that would continue another century, it was played in the season Boston won its final World Series until 2004.

“Certainly the person who carved that didn’t know the Red Sox were going to be denied a championship for so many years,” Jakab says.

As rare as the carvings are, the professional work hasn’t been on display for several generations.

“The stone carvings are completely unknown and these are largely unknown,” Jakab says of the AEF art, “so most of the material you see in here has not been seen before.”

Together they create a very personal portrait of one of the deadliest conflicts in world history.

“Artist Soldiers: Artist Expression in the First World War” continues through Nov. 11, 2018 at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.