There is an old Russian joke that goes like this: Two friends are talking. One says, “Everyone is always sighing: ‘Caruso! Caruso!’ But I listened, and it was nothing special.” “You listened to Caruso?!” his friend asked. “Nah. Rabinovich sang it to me.”

It’s actually more sad than funny. You might be able to describe music to another person. But imagine trying to “sing” what something tastes like.

A few years ago, the European Court of Justice made an important decision. It refused to recognize the taste of food as something that could be copyrighted. The reasoning for this was simple: the taste of dishes and products cannot be protected by law in the same way as the works of writers, artists or composers, because it is impossible to describe it objectively.

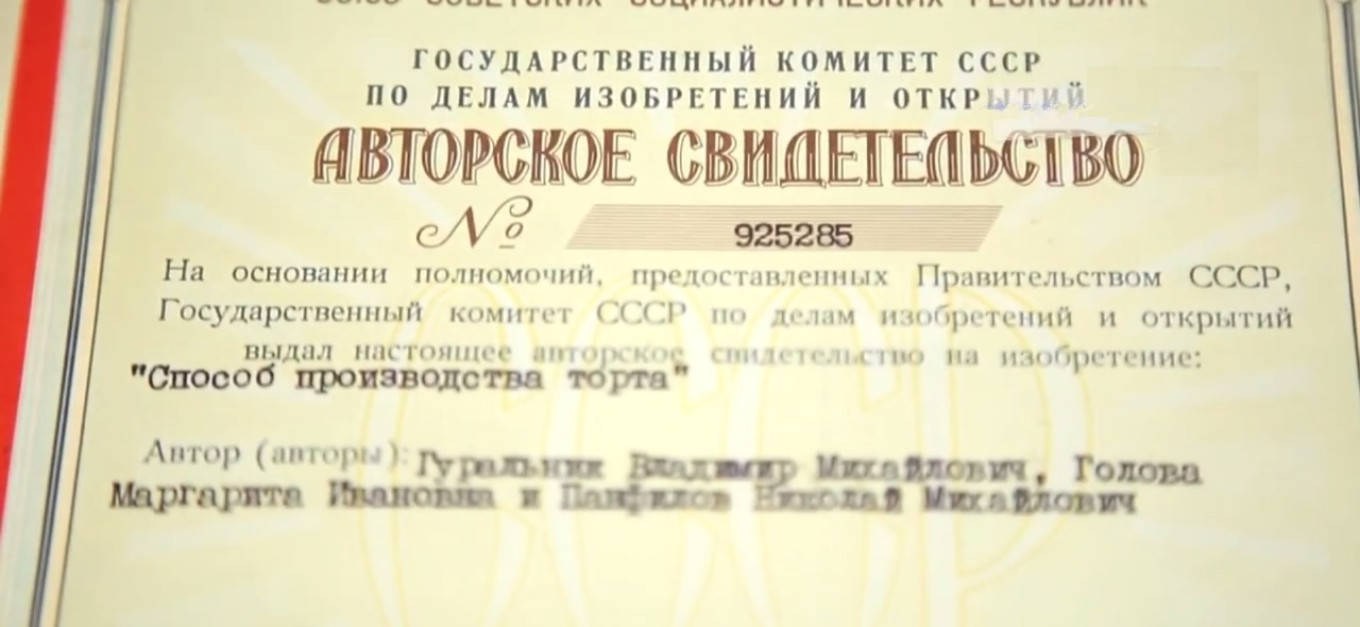

And with that the legal battle between two Dutch cheese producers led to the official confirmation of a long-standing truth. It is, of course, also relevant today. Recipes were traditionally not subject to copyright in either the USSR or Russia. The only Soviet exception known to us was the “Bird’s Milk” cake, for which its creators — Vladimir Guralnik, Margarita Golova and Nikolai Panfilov — received a copyright certificate.

Today, of course, many food products can be patented, including meat (sausages, processed meat, etc.); dairy (cheese, cottage cheese, etc.); confectionery (cakes, candies, chocolate and other sweets); and so on. But the thing is that a patent can protect the composition or recipe of the product, the technology of production, the “construction” (shape, configuration), as well as the design of the packaging. What about the flavor? “Flavor” and “taste” don’t exist in our legal system. Theoretically it is possible to specify in a patent the data of tasters’ analysis, but this is most often an empty theory.

Recipes themselves have never been protected in Russia. The reason is that the criteria of “ownership” are not clear. Suppose, for example, Russian chef Vasily Pupkin adds dill and a spoonful of mayonnaise to a recipe for an omelet from Paul Bocuse. Would that be a different recipe? Or a variation of a classic one? It’s unclear.

Do you think this is just a problem for cooks today? A debate no one cares about? It’s hard to say. There’s a historical aspect to the issue as well. Russian cuisine is our national treasure, after all — its history, how it differs from the cuisines of other nations. And what are we really basing our opinions on? Actually, just ancient names of dishes: telnoye, ushnoye, rassolnoye. And the earliest recipes that have come down to us since the end of the 18th century when the first Russian cookbooks appeared.

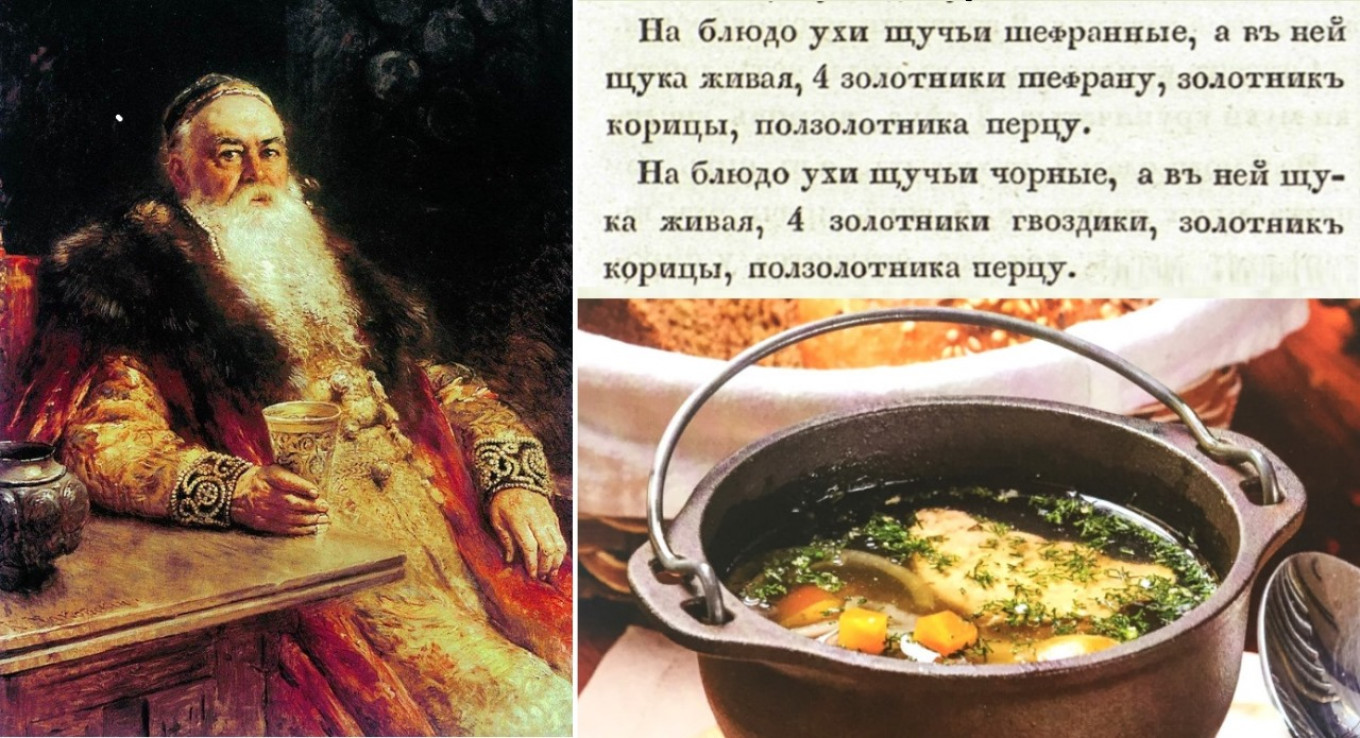

Alas, neither Rabinovich nor Rurikovich can “sing” to us the taste of a kulebyaka in “Domostroi” or the mysterious chowder “yurma.” Taste is not transferred on paper; it can’t be described in words. And if you try, you hit up against the fact that everyone imagines what “bright,” “tart” and “sharp” taste like in their own way. We can’t imagine what was considered spicy at the table of one of the Morozov boyars in the 17th century. You don’t believe us?

See for yourself. Here’s a soup from the “Inventory of Royal Dishes,” 1610: “A dish of pike soup, in it 4 zolotniks of saffron, a zolotnik of cinnamon, half a zolotnik of pepper.” A zolotnik is almost today’s teaspoon. Can you imagine this soup with so much saffron and cinnamon? Of course not!

But let’s put the medieval “Domostroi” aside. We’ve been writing down recipes for over 200 years. Cookbooks and collections of recipes have been published since the end of the 18th century in St. Petersburg and Moscow, including such famous books as “Russian Cookery” (1795-98) by Vasily Lyovshin or “Cook’s Notes” (1779) by Sergei Drukovtsov. There should be no problem with taste there. They codify all the products and how they are cooked. So you can imagine what the dishes taste like, right?

Alas, not everything is so simple. First of all, their “notes” can hardly be called a recipe in today’s sense. “Take a slice of beef, beat it with a shoe to flatten it, fill it with tsibul [onions] and pecherits [mushrooms] and after folding up the edges, put it in the oven until it is ready.” Got it? That’s almost a verbatim quote from Lyovshin’s “Russian Cookery” of 1795. Until the middle of the next century, “recipes” would not have any indication of the weight or volume of ingredients, time and oven temperature, and so on.

But that’s not the worst problem for a cook trying to reconstruct forgotten flavors. Over the centuries, the flavor of many products has changed. Sugar has become sweeter due to better technology, flour is more finely ground, and starch has different properties. Ordinary chicken eggs have become one and a half times bigger. When you read 18th-century novels, did you ever wonder how a traveler ate 10 eggs? How could he eat so much? It turns out that size does matter. And it must be taken into account when an ancient recipe writer tells us to take “5 eggs for the dough.”

The past disappears, sometimes leaving no memory of itself. And the phrase “indescribable flavor” suddenly changes from an enthusiastic exclamation into a sad statement about a culinary experience that is now lost forever.

But thankfully vivid flavor is sometimes provided by spices today just as it was hundreds of years ago. You can experience them here, in one of our favorite desserts.

Pears in White Wine

Ingredients

- 4 firm pears

- 8-10 cardamom pods

- 500 ml (1/2 liter) dry white wine

- 140 g (2/3 c) sugar

- 5 Tbsp lemon juice

- pinch of salt

Instructions

- Peel the pears.

- Crush the cardamom pods lightly with a rolling pin.

- Combine the wine, cardamom, sugar, salt and lemon juice in a small saucepan.

- Place on the heat and bring to a boil.

- Submerge the pears in the syrup. The pears should be completely covered with wine. If not, add a little water.

- Cook for about 30 minutes. The pears should become soft but not fall apart.

- Remove the pears with a slotted spoon.

- Turn up the heat under the pot and boil the syrup down to 1 cup — 10 to 15 minutes.

- Serve the pears with the warm syrup.

It is better to prepare the pears the day before. Delicious with ice cream!

Leave a Reply