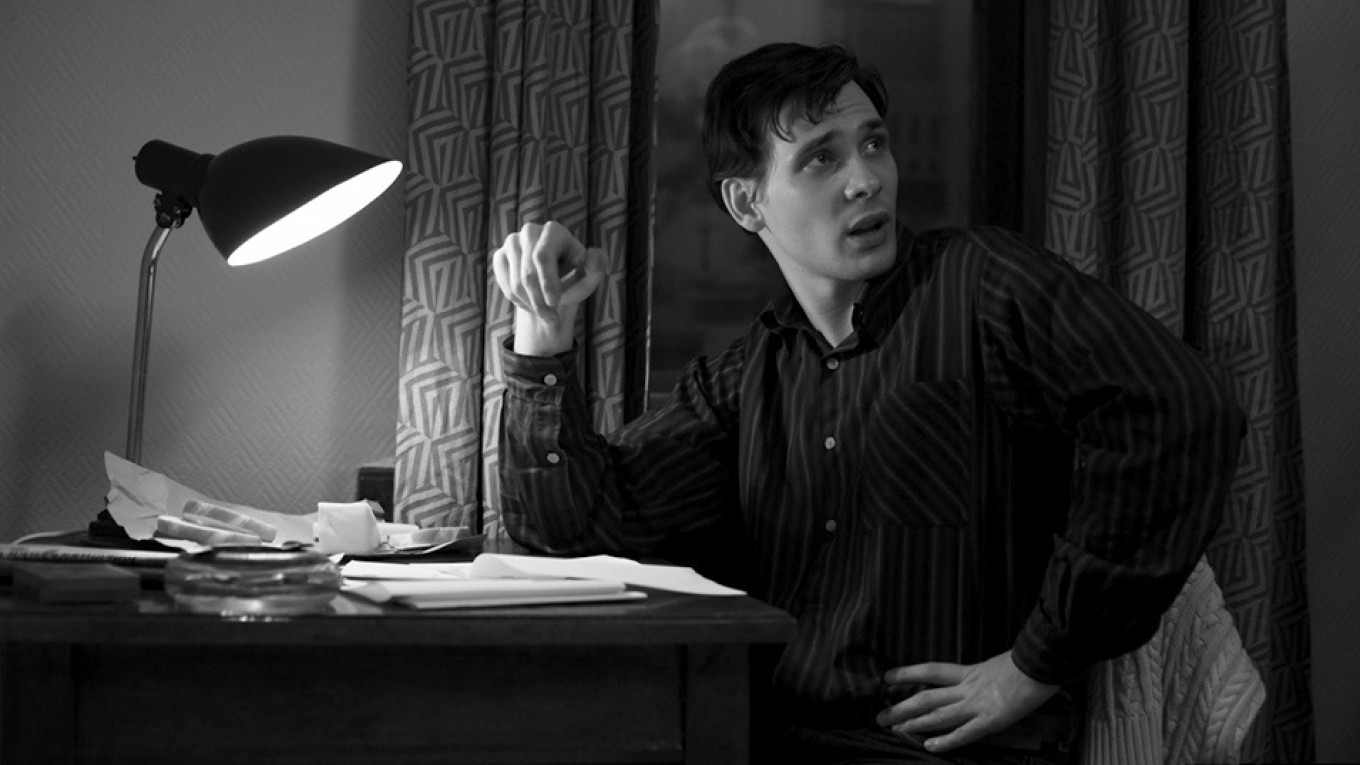

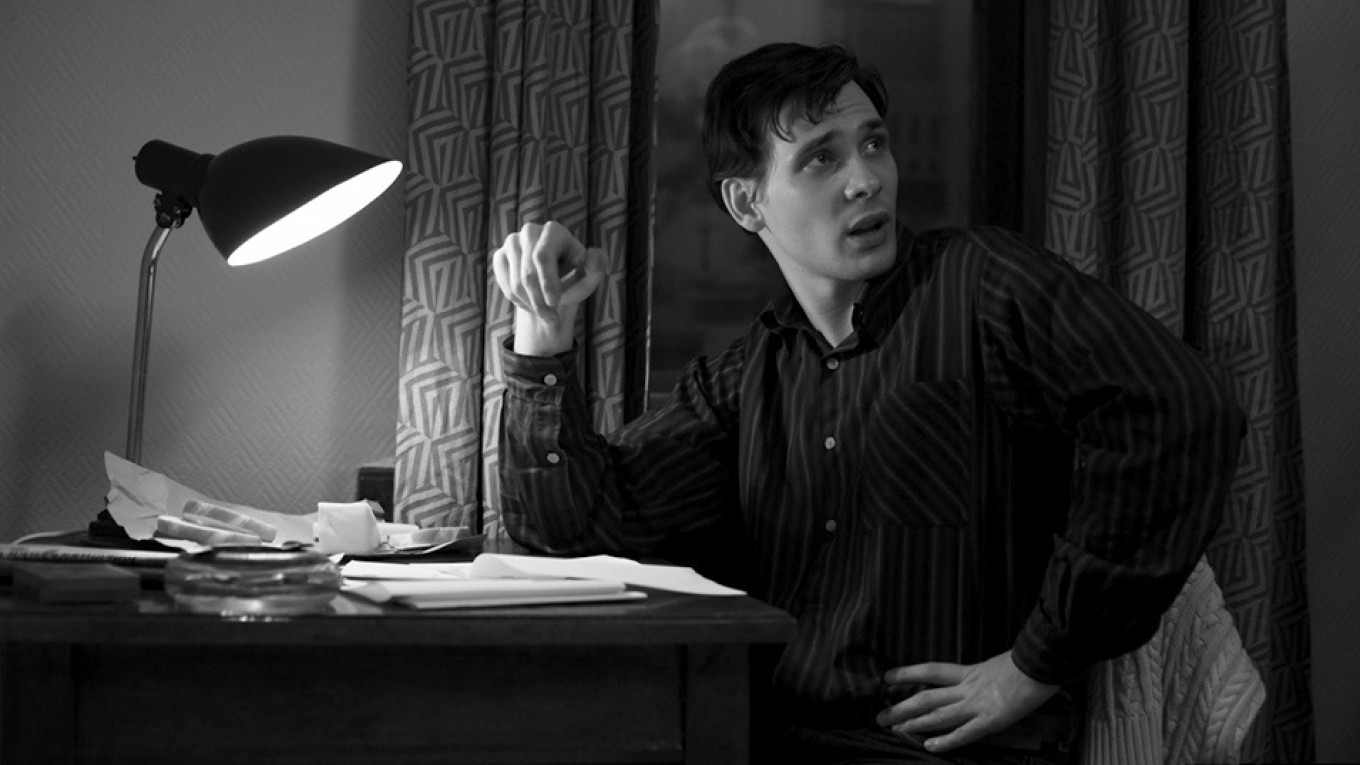

On the last day of October, a film premiered in Moscow that was rare in several ways: it was the first film made by the director in 30 years, it was in black and white, and it was mostly about people who were either recently out of prison camps or on their way in to them. It is called “The Frenchman” and was directed by Andrei Smirnov.

Smirnov is best known for his 1971 film “Belorussian Station” about war buddies who meet up at the funeral of one of the comrades, and “Autumn,” a melodrama about an unhappy marriage and extramarital affair that had a limited release in 1974. After making the 1979 film “By Faith and Truth” about the revolution in Khrushchev-era housing policies, Smirnov quit directing for acting and writing.

Smirnov made “The Frenchman” at the age of 78 and has said in interviews that he has no plans to continue directing. He had planned to make the film on his own and investors’ money, but when the bank that held the financing collapsed, he ended up using his retirement funds.

The film tells the story of Pierre Durand, a young French communist who comes to Moscow in 1957 on academic exchange. It begins at a Seine-side café where Pierre and his two communist friends discuss Marxism, the Soviet Union and the Algerian war from various positions of Marxist orthodoxy — while imperiously sending back a bottle of wine for its unacceptable taste of cork.

In Moscow, where his nearly perfect Russian is explained by being raised by a Russian mother, Pierre begins to research the Russian ballet, his ostensible reason for coming to Moscow State University. But his real purpose is to discover the fate of his father, a member of the aristocratic Tatishchev family. Along the way he falls in love with a proud and flirtatious ballerina at the Bolshoi and gets involved with unofficial culture and samizdat.

Those plot lines weave through Pierre’s acquaintance with Soviet Russia, led by his new friends, official contacts, and happenstance. The kaleidoscope of Pierre’s experiences is familiar to every exchange student during the Soviet era in its general outline, if not in the particulars. There is the obligatory lunch in the home of a Soviet official; ominous chats with the KGB officer assigned to work with students; a Soviet roommate who is an informant; pleas for marriage and an exit visa; trips to an underground jazz club; dinners at the Actor’s Union – where the menu apparently did not change for the next 25 years; a trip on the commuter train out to Lianozovo to see non-conformist paintings; and a glorious New Year’s celebration at the dacha of a rich, pudgy composer married to the fourth in a series of beautiful young wives, with shashlik cooked over a bonfire in the snow, men drinking diluted grain alcohol, women sipping Soviet champagne, and sparklers being waved around the decorated New Year’s tree in the yard.

On his own, Pierre shares a bottle of vodka with a neighborhood drunk in Moscow and a hotel room with two other men and a chicken in Pereslavl-Zalessky. And in one of the most memorable scenes, he goes to a communal apartment to meet two elderly aristocratic Smolny Institute graduates who remember Pierre’s father — “from the Tver Tatishchevs, wasn’t he?” — and amaze him by their precise determination of their obscure familial relationship, and then with the information that one sister spent 12 years in the camps and the other — 18.

With his friends, Pierre listens to the poems of some “new young poets” up in Leningrad named Brodsky and Kushner, read out from a samizdat almanac. The three of them dance down the streets, and two of them share their secrets over port wine in a studio a friend’s father keeps for his love affairs.

In two hours, the film manages to convey the richness and contradictions of life in the Soviet Union of the late 1950s. And somehow, even though there cannot be a happy ending— the film is dedicated to Alexander Ginzburg, who produced a samizdat poetry almanac and paid for it with imprisonment and exile — even the hopelessness seems redemptive and filled with human dignity.

Smirnov, vociferously anti-Soviet, has already enraged the patriotic revisionist-history crowd, who are writing scathing reviews on cinema sites and declaring the film “unwatchable.”

But after the film in a mall multiplex cinema, the audience sat silently and then quietly applauded for a long time.