Everyone knows Maria Sharapova and Catherine the Great, but what about some of the singers, scientists, artists, and other brilliant women who have left an indelible mark on Russian and Soviet history? This Women’s Day, we bring you five lesser-known Russian women whose legacies continue to inspire.

Anna German (1937-1982)

One of the most iconic singers of the Soviet era, Anna German led a remarkable yet tragically short life. Born in 1936 in Uzbek SSR of Polish, German, and Russian descent, Anna’s family would undergo much hardship in the first years of her life. Her father was arrested and executed by the NKVD in 1937, leaving the surviving family members to search for a safe haven in Siberia, Uzbek SSR, Kyrgyz SSR, and Kazakh SSR before finally settling in Poland in 1949. Anna would go on to study geology at the University of Warsaw, while singing informally at weddings, competitions, and festivals. She became popular as a professional singer in the 1960s and toured through Europe and the Soviet Union, performing in a multitude of languages. After being severely injured in a 1967 car accident, she was left unable to perform until 1970. Her return to the stage was celebrated, and she won many awards and continued to sing until her death from cancer in 1982, at age 46. She is most vividly remembered for her popularization of the song “Hope,” which became the unofficial anthem of Soviet cosmonauts, who, legend has it, listened to the song before take-off.

Alexandra Kosteniuk (b. 1984)

Alexandra Kosteniuk broke through stereotypes to become one of the most successful chess players in the world. Born in Perm in 1984, she learned to play chess at home and quickly rose through the ranks of the youth chess competition circuit. She began competing as an adult at age 17, and at age 20 became one of the few women to receive the title of grandmaster, the highest honor in chess. Alongside her ongoing competitive career, she is also a model, actress, marathon runner, and mother.

Princess Ekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova (1743-1810)

Although Ekaterina Dashkova is not as well-known as her contemporary Catherine the Great, she was instrumental in bringing enlightenment thinking to Russia and was among the first female Russian travel writers. Born in 1743, Dashkova demonstrated extraordinary intelligence from an early age and by her mid-teens was a proficient scholar of languages and mathematics, which she pursued at the University of Moscow. She closely aligned herself with Catherine, the wife of then-Emperor Peter III, and was part of the coup that placed Catherine on the throne. Married at 15, Dashkova was widowed by 20, and afterwards sought permission to travel abroad for the sake of her childrens’ education. She would spend many years traveling Europe, as recounted in her autobiography The Memoirs of Princess Dashkova. On these travels she befriended some of the most famous and progressive thinkers of the day, including Benjamin Franklin, Denis Diderot, and Voltaire, and did much to bridge the formerly-distant societies of Russia and Europe. She would return to Russia in 1782 and head the Imperial Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Russian Academy. She maintains a legacy as a pioneer of female leadership and progressive education in Imperial Russia.

Vera Mukhina (1889-1953)

Perhaps no work of art is as emblematic of the Soviet Union as the statue “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman,” which stands in Moscow’s VDNKh Park and was the longtime logo of the Mosfilm film studio. The statue’s creator, Vera Mukhina, was one of the most successful adaptors of the Soviet realism style, and her works remain among the most iconic of the Soviet era. Born in 1889 in Riga (now Latvia, formerly Russian Empire), Mukhina studied art in Moscow, Paris, and Italy in the early years of the twentieth century. Her work became extremely popular in the newly-formed Soviet Union, and she was considered one of the nation’s foremost masters of ideological art. In 1943 she was named People’s Artist of the U.S.S.R. She used her influence to preserve the Freedom Monument in Riga, which was slated to be demolished in favor of a statue of Joseph Stalin. She acted as both an artist and educator until her death in 1953 at age 64.

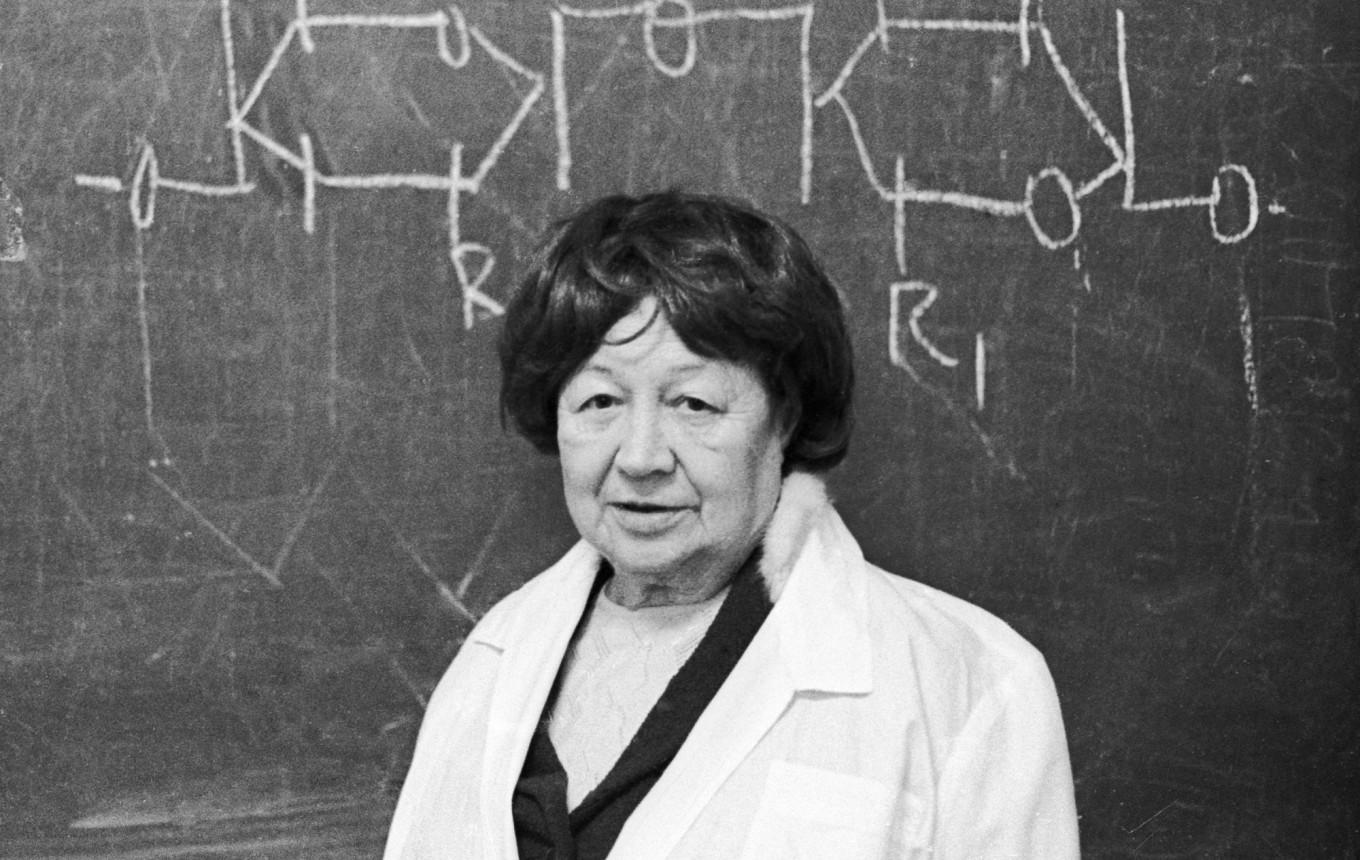

Zinaida Yermolyeva (1898-1974)

This microbiologist saved incalculable numbers of lives with her development of one of Russia’s first antibiotics. Born in the Volgograd region in 1898, Yermoleyva’s choice to pursue medicine allegedly stemmed from her determination to find a cure for cholera, after learning that it had caused the death of Pyotr Tchaikovsky, her favorite composer. She graduated from Donskoi University in 1921 and subsequently conducted experiments on herself as a way of studying bacterial infection. Her audacious findings led to improved techniques of water purification as well as to the eventual development of an antibiotic which was effective against cholera, typhoid, and diphtheria. These achievements proved invaluable during World War II, when they were employed to protect Soviet troops from the cholera epidemic that plagued the German army. Howard Florey, the creator of penicillin, credited Yermolyeva with independently creating an antibiotic on par with his own.