Have you ever looked at the lit windows of random homes and wondered, who is living inside and what their life is like? Kazan’s hospitality had no borders, so here’s a twist to our usual approach: we didn’t meet people in the street or the train this time, we were invited into their homes. Meet three men who were not scared to change their life. 180 degrees. For the better.

Story 1. Dima, Kazan, founder of Chak Chak museum and Tom Sawyer Festival leader

I am from Naberzhnye Chelny. When I was young I moved to Moscow to work for a popular newspaper. First I liked seeing stars in real life. And then I realized that life was only about work and traffic.

Then cars came into my life: I thought that I need to do something more real. I started selling cars and grew to the position of the director of a carshop. And then realized: what’s next? What will I leave for my kids? How will my name be remembered and what mark will I leave in this world? So at 36 I started having middle age crisis.

I met my wife thanks to the car business. I was visiting my parents in Naberezhnye Chelny, and I needed to change the oil in my car. I looked for the oil for my car, but in a local shop they told me they don’t have original. I was mad and said that I would complain. A week later there was a conference with all car shop representatives on the roof of Ritz Carlton hotel. I decided to talk to the boss of that service center from Naberezhnye Chelny and complain, but a beautiful lady came out and I had a glass of wine with her instead.

Together with my wife we developed an idea for a chak chak museum. As we were living in Moscow, we were talking about culture and history of Tatarstan. Once we had the idea, for about a month we lived in Lenin library. Even in today’s digital world when you try to find information on Tatars and chak-chak (ed.note, traditional Tatar sweet, made with dough), there is nothing. We asked to give us all the books on Kazan history. They brought us entire carts full of books. As we were reading them one by one, we found references and wrote it all out carefully. We were digging and digging, it was a lot of work. In one month we shaped the story line of chak chak history.

Two years passed form an idea to realization. There was a question about financing, as at that point we were just employees. We started looking for a house, wrote down a business plan. We tried to take out a loan in the bank but we were told, “This is a risky business.” When we asked what was NOT a risky business, they gave us McDonalds in city’s downtown as an example. Then we started applying for grants, but they told us that we were young and had no prior connection to art and museums. It was true and fair. We thought that the silver lining in this is that we wouldn’t owe anybody. We can be free and flexible.

Then we decided to get advice from state museums… We had to learn what kind of mindset governmental organizations have. At national museums they gave us a brochure on preserving and cataloguing museum items. But we wanted something totally different: to tell a live story of Tatarstan and its cities through chak-chak.

The house where museum is situated used to belong a merchant, a grocer. As soon as the visitors come in, they find out that chak-chak in fact doesn’t have a a recipe. It’s just the soul and hands. Often we heard from some people, “I know that in this village there is an artist who makes the best chak chak in Tatarstan” But when you try to talk to this master in person, it is impossible to get her to talk on how her chak chak is made. Maybe, they are mad that people come to the museum for master classes. Or they don’t want to be filmed by other people.

During an hour tour guides in our museum explore the history of this epic sweet. A visitor goes back to the 19th century, and through chak chak we show the daily life of Tatars, their tales, objects of their daily life and history of traditions. People, for example, used to color their teeth black in order to show that they were rich enough and could afford to eat sugary products, which were expensive at that time.

Apart from the museum, we also curate the Tom Sawyer festival in Kazan. This festival takes place all over Russia. Old Russian homes are being reconstructed by volunteers. They paint them for free, get their facades in order. Our volunteers love history and these houses. People help for entirely different reasons. Someone is tired of his job, he just wants to work with his hands, throw everything out of his head. Somebody comes to meet new people. Also we cooperate with volunteers from France who come on their own budget to help us with houses

Sometimes we face the distrust of people living in those houses. We tell them about the festival, that we do everything for free, and they don’t believe us. If we like the house a lot, and the residents are suspicious, we can go on talking to them for a year: drink tea, get to know each other. It’s a long process, as the color of the paint needs to be coordinated with local authorities. For visual component of the project we use the help of architectures and designers.

It is important to preserve these houses for next generations who should understand our history and architecture. In the city they call us precedent humans. People around us keep saying. “It is not done in this way. You cannot do that.” And we just do it.

Story 2. Kostantin, the homeowner we meet through Dima as his Tom Sawyer festival project

My last name is Lebedev, but I believe that this could have been a made up last name at the end. My grandfather and his brother ran away from the Solovki (editorial note: Soviet prison, a remote place of detention known for its tough inhumane conditions). The two brothers separated and changed their last names so they wouldn’t get caught. Who he really was, we don’t know, he never told anybody.

Our grandfather was a director of a plane factory. My father was also an engineer-constructor who invented planes. He smoked Belomorkanal (editor’s note: the cheapest and strongest cigarettes in Soviet Union) all his life. He died from lung cancer, and I keep his ashtray. There was a good balance in my upbringing: my dad was strict, but fair, and my mom was a kind and a soft person.

When I was a child, I loved taking apart everything: toys, washing machines, tape recorders. I was very curious how a mechanism functioned. Sometimes I could not put everything back together again, but my parents didn’t yell at me for that, and I learned how to work with my hands.

Now this skill is very handy, as I do all the work around the house. My family has been living here since 1949. I was born in this house, my great grandparents, my grandparents and my family all lived here.

The house was built in 1900, when instead of village lodging, there was a great demand for furnished apartments. In provincial towns an intellectual class was being shaped: doctors, teachers. They didn’t want to live in village houses with barn-yards. The house was split into four apartments. When Soviet power got established, they forced urban density by removing the walls in the houses. They put all people in the same flats, which gave birth to the communal apartment. If the house doesn’t become damp, if people live in it and take a good care of it, it will stand for a long time.

Twenty years ago the Kazan downtown looked horrible. It had many old wooden houses that were rundown because of bad care. And all the center was populated by people from low social classes. Kazan had a program to tear down rundown buildings. They tore down the houses in the downtown, and in exchange these houses’ owners were given new apartment for free. It gave them a chance to move out of a house with no drainage, where rats were running around, into a brand-new modern apartment. However, not all people were eager to re-settle.

Our house also was assigned for this program… They wanted to kick us out against our will. But the difference between us and those who agreed to move was that we were taking a good care of our house. Now we live in a state with human rights, but back then in the 90’s nobody cared about that.

Many people who gave their consent to leave; they didn’t have a good life. But for our family the situation was different. We lived in the cultural center, with a school and a shop nearby. The downtown area was becoming better and better and the atmosphere was changing. We were born here, we understood that nobody would give us an apartment with the same space.

And how can you make people move out from their apartment? You might decide to set it on fire. If they don’t want to move, you need to fabricate a case against them or blackmail them. We were threatened with a court decision, and some people showed up at our door and told us to move. I was twenty years old back then, and I took situation under my control. I studied the court decision. We started a battle for our apartment, and I filed a court of appeal. And won. That’s why we are here. I won the fight for my house.

I am an auto mechanic, and I spend 12 hours a day at work. That’s why for me my house is a place to rest. It’s like a bed, your favorite spot: you lay down, you take a rest, you are fresh and awake and you go ahead achieving your goals. When I was younger, I rode a motorcycle, I wanted to become a sailor, dreamt about far away lands, reread all of Jules Verne. But having travelled a bit, I decided that home is better for me.

The house is a place of power. When our previous neighbours were being resettled, many were 90 years old. They had been living here many years, and as soon as they moved to the new apartment, they died. Old people moved in with their stuff and moved out inside a coffin. For an old person it is very difficult to adjust to a new life.

I am a happy person. I can’t complain. My father passed on to me his diligence, I have a house, work. I have two kids, they are healthy, they are fine. A person tends to choose something he is used to.

As the old saying goes: “Habit is a gift from God, it’s the place holder for happiness.”

Story 3, Alexey, another homeowner

Originally our house was built to make money from renting it. In 1896 it was acquired by Peltsam Emanuil Manilovich, he was an ichthyologist, a scientist who studies fish. He never had any systematic education, apart from elementary school, but he became an established member of scientific circles because of his empirical research.

After he retired from Tomsk university, he settled down in Kazan and bought this house. In 1912 he died and we don’t know what happened to the house up until 1934. We know only that it was nationalized by Soviet state and it belonged to Agricultural bank of Tatar republic. My great grandfather was appointed as the manager of this bank in 1934, and he received an apartment in this house. Since then, my family has been living here. Four generations: great grandfather, grandparents, parents and me.

My grandmother used to live here, but in October last year she died. Now I am remodeling the interior on my own and I plan to rent it out to tourists on AirBnb. There used to be a gorgeous interior with a colonnade and a tiled stove, but my grandfather took it apart when central heating came. They were trying to save space back then, as they were assigning living quarters to our apartment during the war. My parents didn’t appreciate this old interior, it was truly Soviet Union Style. All this beauty was covered with sheetrock, and there was a carpet over colonnade.

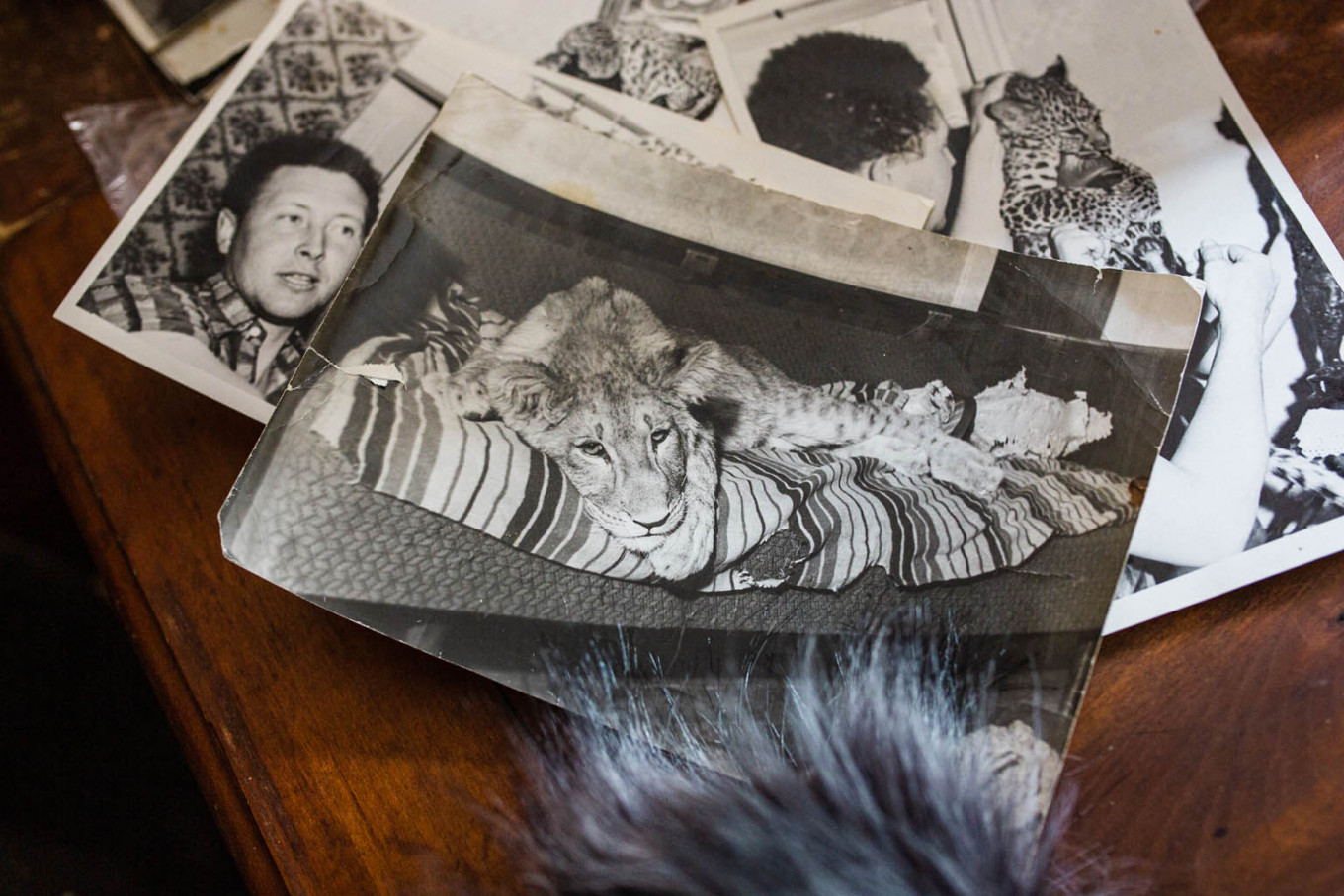

At the end of the 1970s when the country was going through hard times, animals were very sick at the Kazan zoo; some were even eaten by wolves. That’s why my grandmother and father took in different kind of animals: leopards, pumas, and a lion to raise. They nurtured them until they were a year old and then gave them back. Pumas went back to the zoo, and the lion and leopard went to circus.

For a long time I have been searching for a profession that would bring me satisfaction, a profession I could make my living off. In 2005 a professor from Paris University came here to film a documentary. He asked me during an interview, “Are you happy?” For me it was a weird question. I hadn’t heard such a question in my entire life. I said, well, yeah, even though I didn’t understand by which criteria I should use to answer such a question.

In Russia we don’t speak a lot about happiness. Those people I grew up with faced only one question: how to survive? Go to university. Do anything so you don’t have to work as a janitor. After graduating from university you live in darkness. You don’t understand where you are and what you need to do. I went to work as a bellringer in church. However, I didn’t find answers to my existential questions. At some point I started noticing that religious formulas for achieving happiness (penance, admittance to your sins and many others) don’t give me a feeling of happiness. It looks more like kabala slavery.

At the same time I was doing my PhD and working as a research assistant. However, it didn’t bring me happiness either, just horror, suffering and poverty. Then I got into business. We were selling a wine package which turned into a lamp. We did it for couple years, put a lot of effort into it, got tired, but didn’t enjoy it that much. My mother came to terms into my constant search and my unemployment. First she pressured me, but I was shutting her down and she learned to live with it.

To be in search of yourself for such a long time is hard psychologically. That’s why I understand those people who decide to give up. You just have to really hate to work for somebody else, like I do. There is no alternative, you either find your passion, or you will suffer in this life. I can’t suffer, so I will suffer in a different way.

Russian art: literature, paintings, everything is scary. It’s the philosophy of the Russian nation. The idea that suffering is a virtue was always used for the purpose of politics.

I think that happiness consists of several areas. It’s your love life, your relationship to a person next to you, the area of your professional mission. If all areas are balanced, I think you are a happy person. And if you don’t stress yourself out all the time and think about something good, you believe that any situation will result into a good experience. It doesn’t mean that you fly in the clouds or wear pink glasses.

I consider myself an agnostic. Gnosis means knowledge. Agnosis is someone who doesn’t accept such knowledge. I believe that we don’t have enough knowledge to accept certain values as truths. There are no such instruments in this world to understand how it is structured. I can not understand things beyond the concrete and decided not to dig into it. It’s better to concentrate on something I can influence: on my life, so I can live it happily.

This story was first published by Mesto47. You can read this and other stories or listen to a podcast on their site.