‘Cecil Beaton: Celebrating Celebrity,’ the first major show of one the greatest photographers of the 20th century in the Hermitage’s General Staff building brings together about 100 photographs and sketches by, highlighting his role as a herald of celebrity culture and its dedicated advocate.

The display is a collaboration with Cecil Beaton’s Studio Archive and is part of the Hermitage 20/21 project.

Photography as art

True to its name, the display showcases a galaxy of celebrity images: Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe, Gabrielle Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, George Balanchine and Rudolf Nureyev, Marlene Dietrich and George Balanchine. Beaton’s magic was in creating the perfect setting or background to make his subject shine, be it the Russian princess Natalia Palei with mattress springs for a background, or the British Queen Elizabeth with a fine art painting behind her.

But the works in Beaton’s first exhibition in Russia is not limited to celebrity shots. The display pays tribute to his years as a war reporter in the 1940s and his role as official photographer of the royal family of Great Britain from 1950s onwards.

A Russian at heart

While Beaton is not a household name in Russia, his aesthetic sense may come much closer to Russian habits than people realize. Cecil Beaton cared how things looked more than how things were, a trait that the curators believe is very characteristic of Russians.

“It is about how important it is for the Russian people to present themselves in a special way, and how much it matters to them,” Yulia Napolova, the architect of the exhibition and the founder of the PSCulture design bureau, told The Moscow Times. “Russians love special effects, they love to see heads turning after them, they enjoy being popular; and they choose, nourish and arrange their public image and appearances with the utmost attention.”

Beaton’s ties with Russians were quite strong and diverse. He maintained a wide circle of friends among the Russian émigrés in Europe, who played a great role in establishing the cult of celebrity. The greatest celebrities of the era were Sergei Diaghilev, who made the world fall in love with Russian art, and the Russian aristocratic women who were adored by the famous couturiers and became Europe’s first supermodels.

Beaton seems to have shared not only Russian aesthetic values but also the appreciation of luxury, the taste for the finer things in life, and a hedonistic, Epicurean attitude.

“Beaton loved vodka, and he drank it the right way — ice cold shots. That alone tells you everything you need to know about his personality: whatever he did, he made sure it was the proper way,” Napolova said.

A special section of the exhibition is devoted to Diaghilev’s “Russian Seasons.” With his genuine fascination with ballet and the arts, Beaton was naturally enchanted by Diaghilev’s “Ballets Russes.”

“As a child, his mother took him to see Anna Pavlova perform in London, and his heart was lost to dance,” said Daria Panaiotti, the exhibition’s curator. “Years later, when Beaton attended Rudolf Nureyev’s London debut, he compared his powerful emotions with that first overwhelming experience of seeing Pavlova on stage. Beaton had not had a chance to work with Diaghilev directly, the two of them met briefly only once, but he worked with his descendants quite a lot.”

The first selfies

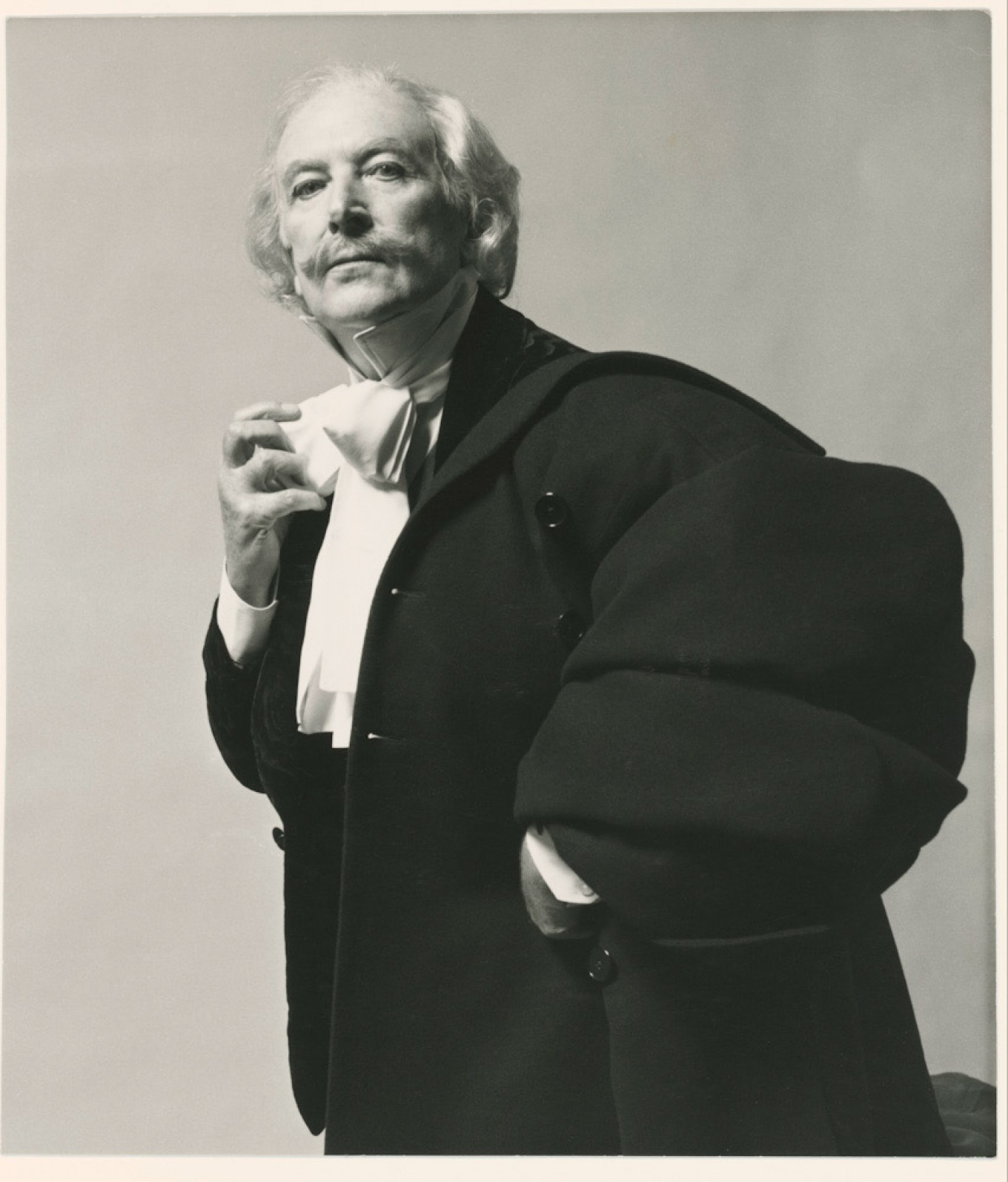

Beaton also visited the Soviet Union in the winter of 1935. Later he spoke with bitterness and disappointment about ‘gawdy’ local fashion and popular culture. The images from that trip include a photograph of Elsa Schiaparelli next to a post box holding bagels and a wintry self-portrait that echoes Boris Kustodiev’s famous painting of Fyodor Chaliapin.

“During the selfie era, the art of Cecil Beaton is as resonant as ever,” Panaiotti said.

“Not only did he know the rules of popularity, he shaped them,” she said. “Today almost all of us seek our own moment of fame through social networks. Beaton’s art gives a new perspective to this trend. His sense of the audience, what is fashionable, how society works, and what would be sure to make a sensation was phenomenal.”

The show is open in the White Hall of the General Staff Building until March 14, 2021. For more information about the show and visiting the museum, see the Hermitage website.