On Tuesday Russia’s best-selling novelist Guzel Yakhina presented her third novel, “Train to Samarkand” (Eshelon na Samarkand), in an online press conference.

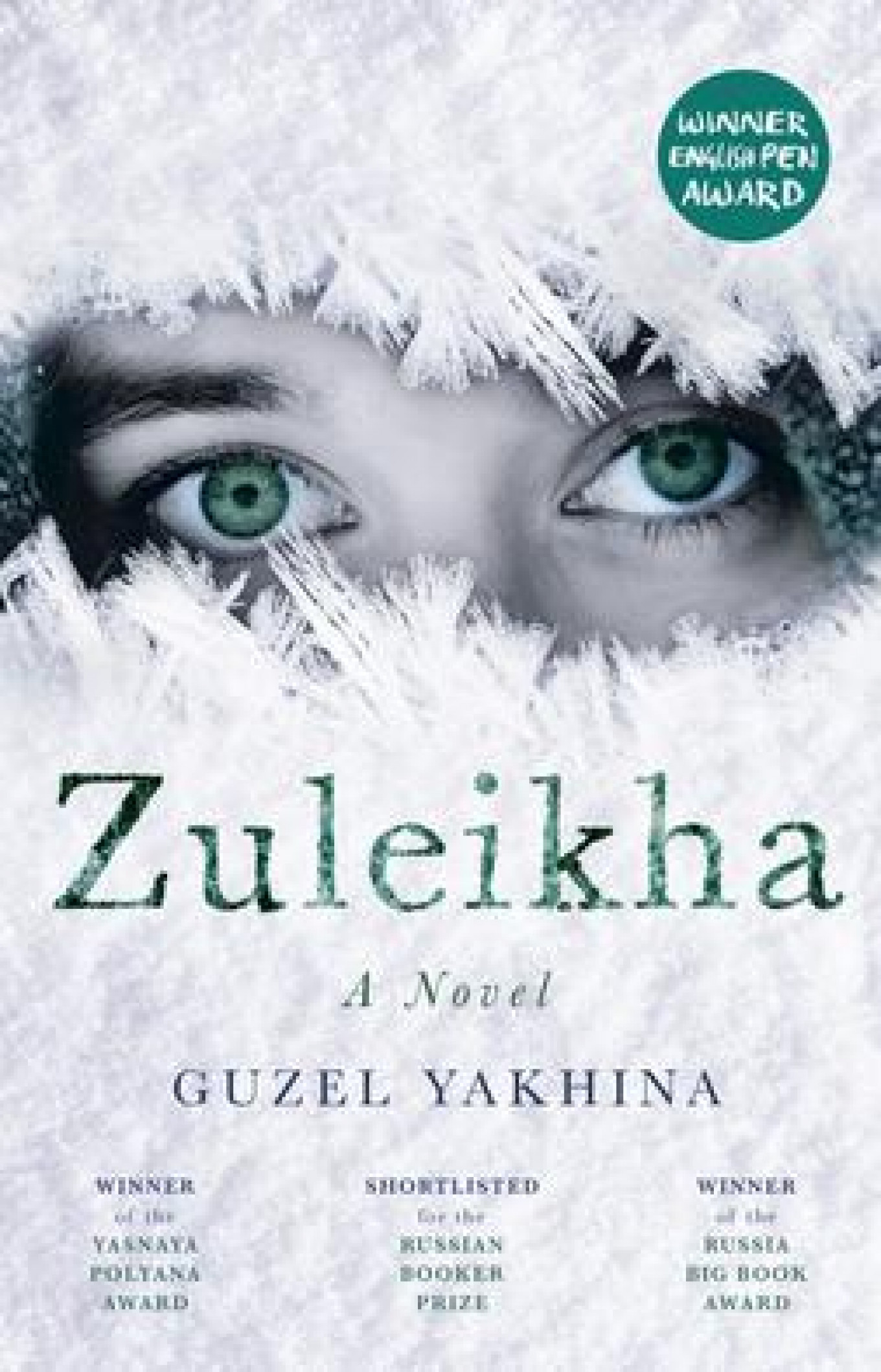

Yakhina took Russia’s literary world by storm in 2015 with the publication of her first novel “Zuleikha Opens Her Eyes.” It won the Yasnaya Polyana and Big Book awards, was translated into over 30 languages, and was made into a television series.

Both “Zuleikha” and Yakhina’s second novel “My Children” explore some of the most traumatic episodes of early Soviet history while shining light on the unique experiences of Russia’s ethnic minority communities.

“Train to Samarkand” continues to focus on the country’s painful past. It tells the story of orphaned children evacuated from Russia’s Volga-Ural region during the famine of the early 1920s, also known as the Povolzhye famine.

“Difficult but compelling”

When Yakhina set out to write a new book more than two years ago, she thought the topic would be the “dreams and difficult childhood” of orphaned children in Tatarstan’s island town of Sviyazhsk. But, she said, “As I was diving deeper into the topic and the [history] of the early 1920s, I realized that the civil war and the famine defined the lives of everyone back then.”

And so, the famine, which took the lives of over 5 million people, became the “invisible but central character” of her novel.

In order to “talk about the difficult subject in a compelling way,” Yakhina set the novel on a train where 500 orphans are being transported from the starving Povolzhye region to “well-fed” Samarkand (then the capital of the Soviet Turkestan).

Though the children’s perspective remains fundamental to the novel, its central character is a young red army soldier, train commander Deyev, who is tasked with overseeing the journey.

Deyev’s character not only embodies the complexities of the time — an executioner in the past, he is these children’s savior in the present — but also allows Yakhina to play with the reversal of traditional gender roles with Deyev and the childen’s commissar Belenkaya, his love interest.

“It is a backward couple because the man encompasses all the [traditional] female traits and the woman encompasses the male ones. But they also have a purely ideological disagreement about kindness and what ‘saving the children’ really means,” Yakhina explained.

The ideological stand-off between and within the central characters, the romantic story line and the stories of adventure woven through the book are meant to balance out the grim historical realities that are the basis for the novel.

Like the story of Zuleikha, “Train to Samarkand” echoes Yakhina’s family history — her paternal grandfather was transported to Turkistan in 1922 — but to write this novel, she undertook an enormous amount of archival research.

“Everything that happens with children in the novel is, for the most part, [historically] accurate.”

“For example, the history of a boy named Yegor ‘The Clay Eater’ who ate clay during the famine is based on true facts,” Yakhina said. “The story of a boy named Senya ‘The Chuvash’ who was haunted by a giant louse in his dreams is also true. I read about that boy in the memoirs of [social worker] Asya Kalinina.”

Hope for reconciliation

Both Yakhina and her publisher said that despite the vast availability of archival materials, the topic of the Povolzhye famine is largely overlooked in Russian literature. Yakhina mentioned the 1927 novel “The Sun of the Dead” by emigree writer Ivan Shmelyov as the best-known work on the topic. Now, nearly a century later, she thinks this is the right time to reopen the subject.

“There is a growing need to have an honest discussion about the Soviet past. Such discussions were widespread in the 1990s, but in the early 2000s the interest in them began to fade as we were more concerned with the present. Now I think we are ready for that conversation.”

In the past, Yakhina’s literary works have served as facilitators of that discussion. When the on-screen adaptation of “Zuleikha” aired on a Russian state channel, the reactions to it ranged from praise for shining light on stories of silenced communities to criticism for attempting to “rewrite” history.

The author, however, is unfazed by the polarized reaction, saying the resulting conversation helps “to slowly squeeze the Soviet” out of Russian people. When asked whether she expects “Train to Samarkand” to have a similarly divisive effect, she stays firm.

“I understand that this novel might again spark the discussion about whether it accurately conveys the past and how accurate is the amount of tragedy in it… but my conscience is clear.”

Her patience and conscience were tested almost immediately after the press conference, when a local historian accused her of plagiarizing his history blog. Yakhina responded that she used dozens of archival sources when writing her novel and there are bound to be similarities with other fact-based accounts. “I speak of the past truthfully,” she said of her novel, “but I don’t make a diatribe [against history].”