ST. PETERSBURG — A museum about LGBT history opened to visitors in Russia’s second-largest city this week — but it looked set to be accessible for only a few days before it is banned under draconian “gay propaganda” laws expected to come into force imminently.

“The museum is a political act,” said Russian LGBT activist Pyotr Voskresensky, who set up the exhibition in his city center apartment.

“As this era is coming to an end, I felt I wanted to say one last word.”

The legislation on LGBT “propaganda,” which was passed by upper-house lawmakers Wednesday, expands on a 2013 law and will prohibit any public information or action that mentions homosexuality — including movies, literature and online content.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is expected to sign the bill into law in the coming days.

Russia’s LGBT community already faces violence and marginalization as a result of widespread homophobia, which is often fueled by official rhetoric. But activists fear the new law will make the situation far worse, pushing the country’s LGBT community entirely underground.

Voskresensky — who has spent years acquiring Russian-made statues, jewelry, vases, books and other art objects that tell stories about the country’s LGBT subculture — decided this was his last opportunity to share his collection with ordinary people.

For safety reasons, the museum’s location has not been made public: hopeful visitors must contact Voskresensky via Facebook to receive the address.

On a recent tour, the first thing visible to visitors at the entrance was a portrait of composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky, one of the most famous gay men in pre-revolutionary Russia.

Voskresensky said he came up with the idea of opening an LGBT exhibition during a visit to Tchaikovsky’s house museum in the Russian town of Klim.

Other exhibits include a statue and a number of Russian-made pieces of jewelry representing Antinous, the homosexual lover of Roman Emperor Hadrian, who became a gay icon.

Some exhibits conveyed a clear political message — like a statue of Harmodius and Aristogeition, two gay lovers, who, according to legend, assassinated an oppressive ruler.

“As an activist I found it personally inspiring,” Voskresensky said of the story.

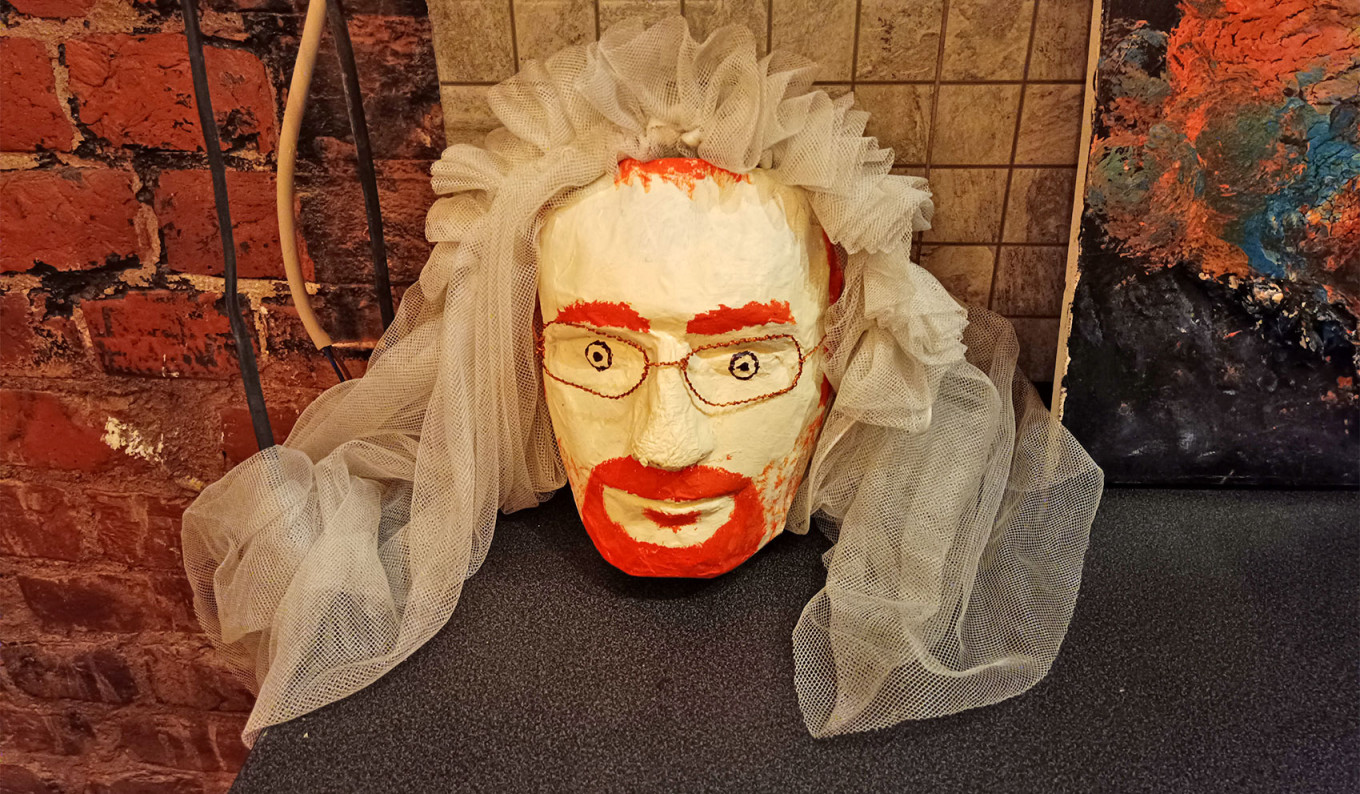

At the end of the exhibition, there were a few contemporary art pieces, including a satirical model depicting Russian parliamentary deputy Vitaly Milonov, a prominent supporter of the anti-gay legislation, wearing a bridal veil.

“It’s a normal policy for authoritarian leaders to pretend that we don’t exist,” said Karina, 27, a LGBT activist from the Central Asian nation of Kyrgyzstan who was touring the rooms.

She said she was in St. Petersburg as a tourist when she found out about the museum.

“I am happy to see that there are people who gather collections like this, talk about it and increase the visibility of our community,” she said.

As soon as the anti-LGBT law is on the books, however, Voskresensky’s museum will be illegal.

Under the law, any display of “LGBT propaganda” will be punishable with fines of up to 400,000 rubles ($6,500) for individuals and up to 5 million rubles ($80,000) for organizations.

There are likely to be significant consequences not only for LGBT organizations, but also LGBT venues as well as books, films, theatrical plays and video games with LGBT content.

But what worries Voskresensky most is that the new law could encourage vigilante violence.

“The most scary thing is that our state is losing its monopoly on violence,” said Voskresensky pointing at cases of LGBT people who have been harassed, attacked and even killed in Russia in recent years.

Another visitor to the museum, Anna, said when she read about the exhibition on social media she realized she had to attend before the anti-LGBT laws came into force.

“I realized this was a unique, historical opportunity,” said the 22-year-old, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

“It shows that ideas resist even when they are under pressure, and as soon as the pressure is lifted and it gets a bit more free, people will be able to express themselves again.”

Voskresensky said he plans to shut down the museum and attempt to move the exhibits abroad.

It “could become a point of attraction for other collectors and grow in size,” he said.

Above all, Voskresensky hopes that the exhibition, which showcases the deep roots of gay culture in Russian history, will survive as proof against Kremlin narratives suggesting Russia’s LGBT movement is an artificial construct imported from Western countries.

“The museum clearly shows that what authorities say is a modern invention is just their desire to see the past through their idea of the present,” he said.