The abundance of appetizers on the Russian table has always amazed foreign guests. The custom of drinking a shot or two of vodka before dinner was unusual in Europe, although once foreigners got used to Russian cuisine, they didn’t turn down the vodka. And once they got used to the vodka, the understood the necessity for the overflowing plates of appetizers.

In wealthy homes of the 18th century there was even a special table for appetizers called a postavets. Imagine the scene: guests come in from the cold. They do not sit down at the table at once. First they socialize in the living room, and of course they’d like a drink. That’s where the postavets came in— a special buffet table in the corner. It was just the thing. The appetizers — caviar, salmon, marinated and roasted meat — alternated with favorite drinks, such as infusions and fruit and berry brandies.

The arrival of new alcoholic beverages from abroad often inspired new appetizers to go with them. This happened with cognac. Of course, you might take a bite of a nice morsal of ham after a sip of cognac, but somehow cognac and ham do not produce the symphony of taste one wishes. At the beginning of the 20th century, Shustov’s cognac became extremely popular in Russia. Nikolai Shustov produced the drink in Armenia, laying the foundation for the future glory of Armenian cognac.

At the beginning of the 20th century the name “cognac” was not protected, so any producer in any country could write the word on their labels. Shustov used it very successfully.

Shustov’s greatest dream was to become a Supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty. History is silent on how exactly he managed to pull this off. But we do know that at one holiday gathering he served Tsar Nicholas II a glass of his best cognac. But Shustov was a rather clever man, and ahead of time he made an agreement with the chefs in the imperial kitchen to prepare and serve the Tsar a light appetizer as a “chaser” to the cognac. The chefs did not puzzle over it for a long time. They needed something that could be served outdoors — where the reception was being held — and wanted to make a bit a of surprise. So they served slices of lemon on a platter. But not just any lemon. These were “imperial lemons.”

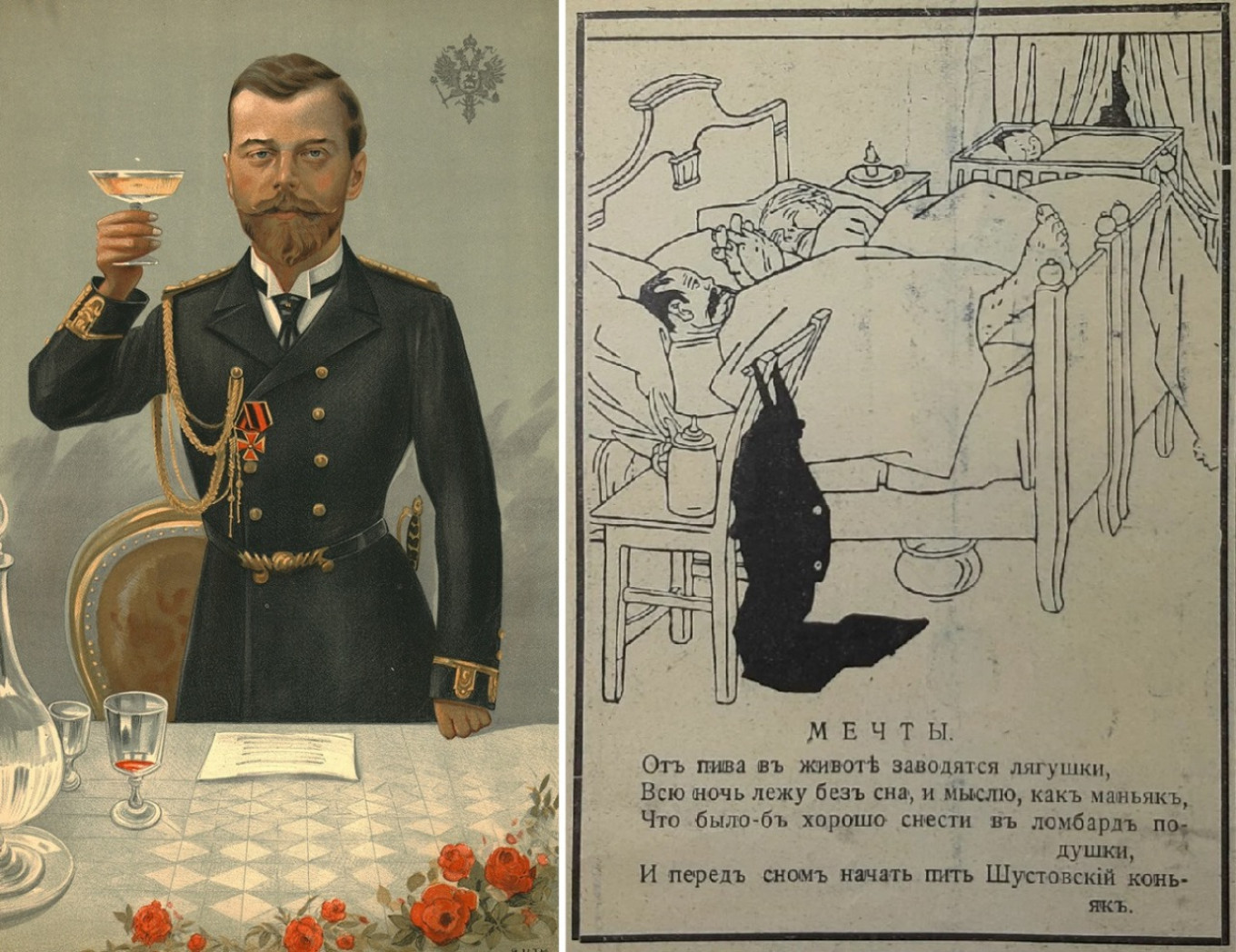

Above: Tsar-Father. Caricature of Nicholas II by Jean-Baptiste Guth (Jean-Baptiste Guth) for the magazine Vanity Fair from October 21, 1897 and Shustov’s Advertisement (1912): “Bring your pillows to the pawnshop and drink Shustov’s brandy before bedtime instead.”

Each slice of lemon was sprinkled with powdered sugar on one edge and finely ground coffee on the other. The cognac and appetizer impressed the Tsar, sealing the success of Shustov’s business The appetizer was also a great hit and was called — out of the tsar’s hearing — “Nikolashka.” Over time, true connoisseurs changed it a bit: they laid a thick layer of black caviar on the slice of lemon.

The hard years of revolutions and wars in Russia washed away this cultural layer of gastronomy, leaving only the basic foundation of the national cuisine. In the 1920s the tables of many townspeople and villagers went back in time 150-200 years. Many refined and colorful dishes, salads and appetizers disappeared. Only the “base” of Russian cuisine remained: cabbage and thin soups, porridge, and primitive fried eggs with a bit of dried salt pork and boiled potatoes with herring. And this was in the best case, when people could rustle up a little nob of butter for those simple foods.

Appetizers are, in our observations, the dishes most sensitive to a change of circumstances. There will always be soup and porridge — during revolutions, wars, perestroika and any other conditions. But appetizers are subtle dishes. If anything goes wrong in the country, they disappear from the menu. Even in the famous “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” (1939) there are only two pages of hot appetizers — just nine recipes: ham, sausages, sardines, sausages, kidneys on toasted bread, mushroom tarts, sardines in a puff, sprats in puff pastry, and simple stuffed bread croutons. That’s all!

No wonder that in these difficult conditions meat and fish appetizers were gradually replaced by vegetables. For many years salted cabbage, pickles and mushrooms became the most popular dishes for the beginning of the meal and the first shot of vodka. And it must be said, many hostesses achieved real perfection here. Some amateurs even found secret pleasure in it. The old saying that “an appetizer lowers the alcohol proof” certainly doesn’t apply to cabbage and mushrooms. Unlike salt pork or salted fish, they make intoxication much easier. But some people liked it — it was a way to save both money and vodka.

But life does not stand still. Even vegetable appetizers can be elegant and original, especially with autumn’s bounty of vegetables. They can be transformed into a wonderful dish to enjoy in the winter. Here is one of our favorites.

Sweet Pepper Lecho

Note: You can use green (not fully ripe) or red (ripe) peppers.

Ingredients

- 5 kg (5.5 lb) seeded and cleaned peppers

- 5 kg (3.3 lb) ripe tomatoes

- 200 g (1 cup) granulated sugar

- 200 ml (7/8 c) vegetable oil

- 2 Tbsp salt

- 2 Tbsp tomato paste

- 30 ml (1/8 cup) 25 % spirit (pickling) vinegar

- 1 tsp whole black peppercorns

Instructions

- Sterilize the jars.

- Cut the peeled peppers into straws about 1 cm wide and put them in a deep pot.

- Cut the tomatoes into small pieces and pulverize with a blender until smooth.

- Add the tomatoes to the pot with the peppers.

- Add all other ingredients: sugar, salt, tomato paste, vegetable oil, vinegar, peppercorns. Sir well.

- Put the pot on the stove and bring to a boil over medium heat.

- After it comes to a boil, cook for 10 minutes and then laddle into sterilized jars. Seal with lids.

- Cover the jars with a thick towel and leave until completely cooled.

- Store the lecho in a dark, cool place.