Residents of Ulan-Ude in Russia’s Far East republic of Buryatia were taken by surprise to learn that local authorities plan to construct a new prison for 3,000 inmates near their homes.

“We were not informed about this terrible news that they plan to build a mega-prison, a special regime zone,” one local resident said in a group video appeal to officials. “I really don’t know who could decide to settle criminals right in the regional capital.”

The news has sparked resistance from thousands of citizens in Ulan-Ude, a city of 436,000 people near the eastern shore of Lake Baikal, in the latest example of Russians pushing back against authorities and corporations seeking to encroach upon green spaces near their homes.

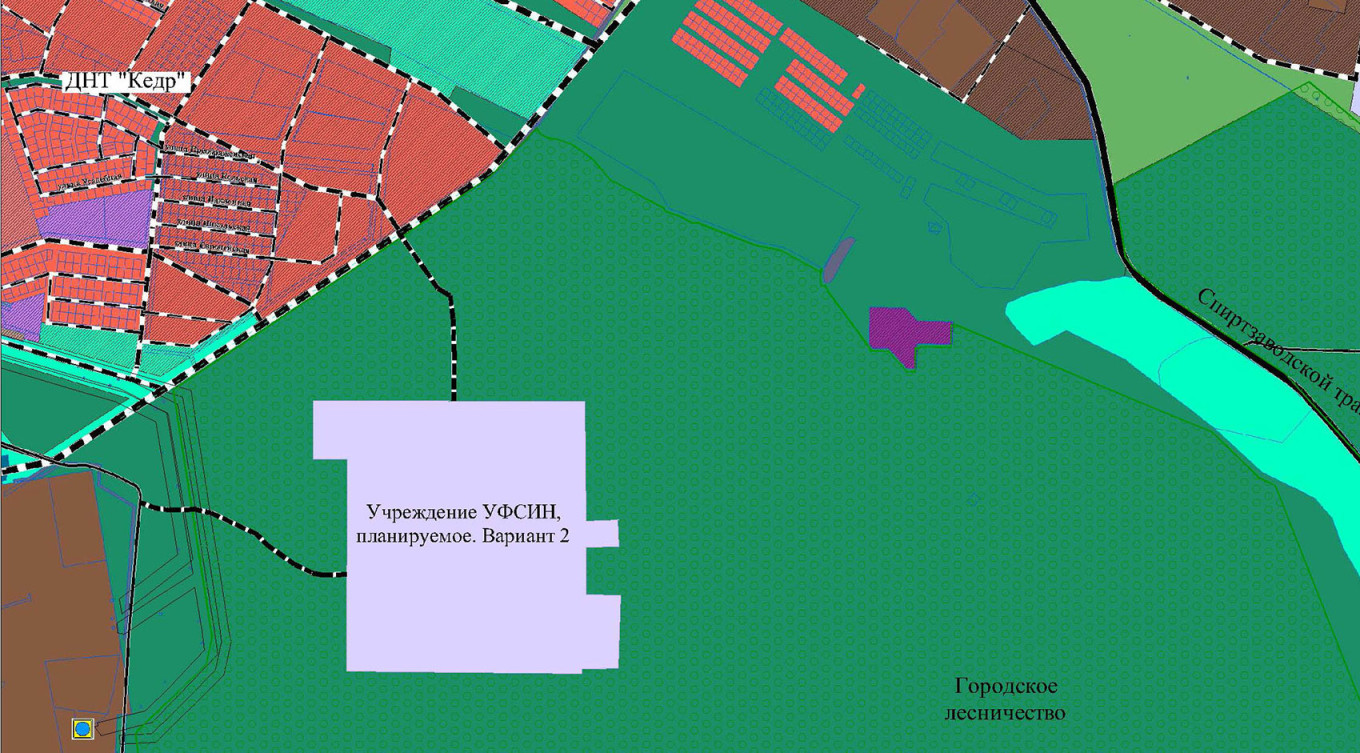

The proposed penal institution, costing 26 billion rubles ($296 million) and intended to replace an aging, century-old prison in the city center, will require about 80 hectares of forest to be cleared, the residents said.

“Ulan-Ude is one of the three dirtiest cities in Russia. And you want to cut down a pine forest covering an area of 80 hectares? No, this is a disaster. We categorically disagree! We will defend our violated rights!” the anonymous speaker added.

The resistance from the city’s Energetik district began after residents of another neighborhood, Steklozavod, voted against the construction of the mega-prison in their backyard during public hearings in early December.

However, the activists argue they were not properly informed about the hearings and insist on relocating the facility beyond the city limits, with their demand already gathering 6,000 signatures.

The authorities claim that the project will boost the local economy by creating a “modern facility with additional job opportunities,” Buryatia’s head Alexei Tsydenov said at a meeting with President Vladimir Putin in March 2023.

In response to the activists’ concerns, Tsydenov said in December that moving the prison outside the city could compromise its efficiency, as the facility needs to be accessible to all those working there.

“The combined pre-trial detention center and prison will not be close to residential or social facilities,” Tsydenov said. “It will stand separately and not have any contact with anyone.”

He also warned that the Steklozavod district’s residents may later regret missing “such an opportunity for the development of the neighborhood.”

Despite these assurances, activists remain unconvinced, reiterating their desire to preserve “the lungs of the city.”

“Please listen to the residents, we don’t want the forest to be cut down,” one citizen said at an Ulan-Ude residents’ meeting in mid-December. “I believe that the forest is a common heritage, and the whole city should be interested.”

Precious greenery

The logging of the 80 hectares, roughly 1% of Ulan-Ude’s total forest area, would deal a “severe blow” to the environmental well-being of the city’s residents, biologist and forestry expert Alexei Yaroshenko told The Moscow Times.

“Plus, there is associated infrastructure that will require further deforestation,” Yaroshenko said. “Moreover, the additional fragmentation of forested areas typically leads to a reduction in their overall resilience.”

Cutting down green areas near people’s homes in Russia nearly always leads to public discontent, which often escalates into protests, Dmitry Morozov, a coordinator for the Forest Coalition of Moscow, an association of over 30 grassroots groups, told The Moscow Times.

“For the residents of industrial cities, nature is not just a beautiful decoration for walks or a pleasant view from the window — it is their health and the health of their children,” Morozov said.

In the case of Ulan-Ude, the prospect of living next to a giant prison could mobilize many more people beyond those who are concerned with the environment, said Morozov, who receives five to six requests for help from activists across the country every week.

However, even the most vocal public protests against logging in Russia over the last two years have practically ceased to yield results, Morozov said, pointing to Moscow’s Troitsky Forest, where residents actively opposed the felling of centuries-old trees to no avail.

“Troitsky Forest was supposed to be another victory [of the environmental movement] — like Yekaterinburg’s garden square, Shiyes and Kushtau — but was unlucky to find itself in a new historical reality where dialogue with the authorities from the position of ‘we are against’ no longer works,” the expert said.

‘Negative background’

The mega-prison in Ulan-Ude may be not the only one on the horizon. The development plan for several of Russia’s Far East territories envisions the construction of a similar facility for 3,000 detainees in Chita, the capital of the Zabaikalsky region.

Elsewhere in Russia, a 4,000-bed isolation facility has been operational in St. Petersburg since 2017, while the Kaluga region south of Moscow announced plans for the construction of a 3,000-inmate prison settlement in 2021.

Activists from the Gulagu.net prisoner’s rights project have recently observed a sharp drop in the number of prisoners in Russia due to the deployment of inmates to the frontlines in Ukraine, the project’s head Vladimir Osechkin told The Moscow Times.

He therefore sees no need for Russia to construct new penal colonies.

“We understand people’s reluctance to have a mega-prison nearby, where they will soon be sent,” Osechkin said. “Russia needs hospitals and rehabilitation centers for the tens of thousands wounded in the war, not prisons.”

A prevailing negative outlook among Russians toward convicted individuals ignores judicial errors and the fact that many people serve unjust sentences, Moscow-based lawyer and human rights defender Valentin Bogdan told The Moscow Times.

“The negative attitude stems from the general opinion: why do we need such a grandiose building nearby, which, in fact, scares and creates this negative background?” Bogdan said.

Despite prisons partially emptying due to inmates departing for the war, the construction of new facilities may still be necessary to improve the conditions of detainees in Russia, which has the highest number of prisoners per capita in Europe.

Many facilities date back to the tsarist era and fail to meet modern norms, Bogdan said.

“It is indeed necessary to get rid of old prisons and build new ones in their place to meet standards of lighting, humidity, temperature, warmth, everything must comply,” he said.

Bogdan noted new job opportunities and a more convenient location for inmates’ relatives as positives of the planned facility in Ulan-Ude.

He also pointed to a cluster of correctional institutions in the republic of Mordovia some 500 kilometers east of Moscow — colloquially referred to as “Mordovlag,” a derivative in Russian from “Mordovia” and “labor camp” — which he has visited several times.

“These zones serve as city-forming enterprises, so to speak,” Bogdan said, using a Russian-language term for a single industry that dominates a monotown.

“As they joke there, half of these settlements are serving sentences, and the other half is guarding them,” Bogdan said.

Mounting troubles

In Ulan-Ude, however, the concerns about the mega-prison are piling up on the already unnerving everyday life of Buryatia’s people. The region ranks 81st out of Russia’s 85 regions for quality of life, with persisting problems such as air pollution in several places, including Ulan-Ude.

Buryatia is also among the regions with the highest casualties in the war in Ukraine.

The mega-prison will “complete the picture,” said Alexandra Garmazhapova, the president of the anti-war group Free Buryatia Foundation who currently resides outside Russia.

“Buryatia today is a miniature version of Putin’s Russia,” Garmazhapova told The Moscow Times.

“And a prison camp is a backbone enterprise for a city. Not an IT cluster, for example, but a prison. And this says more about the current [political] regime than anything else.”

Ulan-Ude’s residents face a potentially tough struggle ahead. In mid-December, they invited 25 deputies to a meeting, but all the invitations were ignored.

Morozov said that the reputation of many members of the country’s ruling elite is now at stake.

“A project of this scale, especially one initiated by the president and supported by the applause of the entire local power vertical, cannot be easily reversed,” Morozov said.

“The only way for the residents is to formulate an alternative project: propose building the prison in another location and actively promote their initiative, drawing the attention of the president up to the elections in March.”

Activists contacted by The Moscow Times declined to comment for this article, saying they were reluctant to speak to foreign media.

The Ulan-Ude city administration did not respond to The Moscow Times’ request for comment.