Dogs /canis/ 10.2 X 6 cm; 10.2×2.5 cm; 10..2 X 6.5 cm

In original “Physiologus” the chapter on dogs was omitted. In the bestiary the antique tales about the dogs collected by Pliny and Solinus are being revised and newly interpreted. The text of the bestiary includes passages originating from Isidor /XII.II.25—27/ and from St. Ambrose. From Isidor comes the world “canis” derived from the Greek

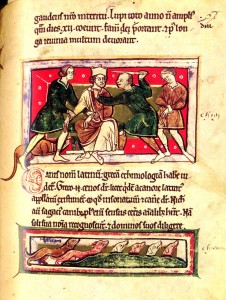

or the Latin “canor” /singing/ which reminds one of the dog’s howling. The small miniature at the bottom of page 28 showing a number of small pups of various colours illustrates the story in the bestiary about the diversity of dog’s breeds. Dogs respond as their names are called out, love the master and cannot live without man. The story tells us that when the legendary king Garamantes was captured by the enemies his dogs once rescued him. This tale often serves as an illustration to stories about dogs. When Jason was killed in a quarrel, his dog refused to eat and died of hunger. The hound of King Lisimachus threw himself into the flames of his dear master’s funeral pyre. Then follows the story about the dog of a Roman, who followed his master after he had been executed, and when the corpse was thrown into the Tiber, the dog tried to save the body. There is also a famous story about the dog who, after his master was murdered, found the killer and proved his guilt before the King’s court. This story was often recited and more details were added to it, up to the end of the eighteenth century it was one of the most popular tales about dogs.

The descrpition of a vast diversity of dog’s breeds originating from Isidor is repeated in the works of Pseudo-Hugh /11.17/ and Pierre of Beauvais /IV.75/. It grows larger in the writings by Albert the Great /XXII.16/ and Brunetto Latini /I.V.186/.