“An infected mouse escapes from the Institute of Functional Immortality, where the development of a means to prolong Putin’s life is underway. An apocalypse occurs in Moscow: most of the city’s inhabitants die, some survive, and the rest turn into zombies.”

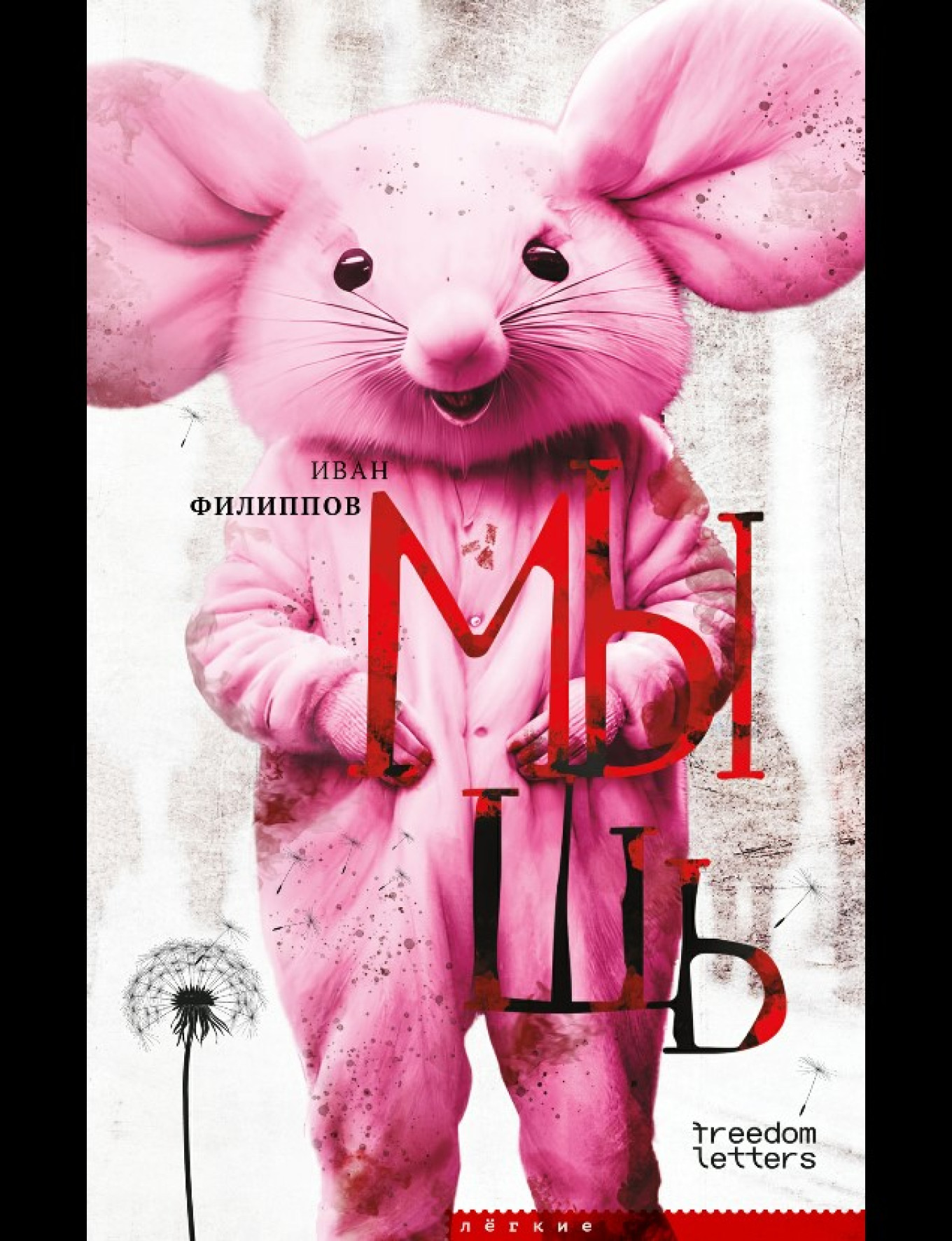

Freedom Letters on “Mouse” by Ivan Filippov, 2023

“The war is over. The dictatorship has collapsed. Russia is free again. But for how long — that is the question.”

Babel Books on “The Devil’s Advocate” by Boris Akunin, 2022

“The heroes of the collection did not want to become hostages of official propaganda, decided to cut the state’s strings, were not afraid to express their position against Putin’s aggression.”

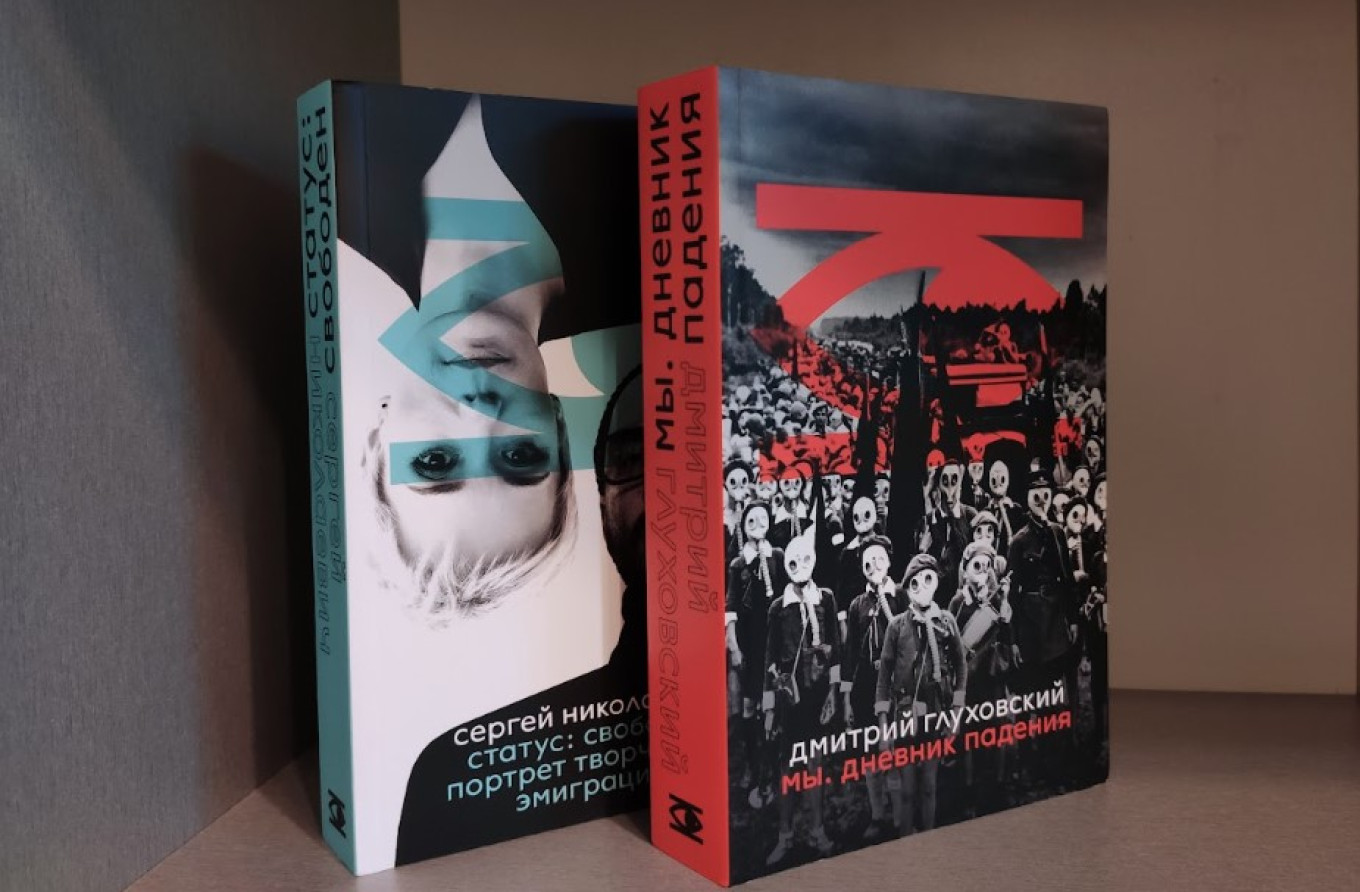

Vidim Books on “Status: Free” by Sergei Nikolaevich, 2024

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine entailed a full-scale return of censorship. It quickly became dangerous to publish books that like the ones above in Russia. And so these books are being published, advertised and sold through the websites of Russian-language projects registered abroad.

Back to the past

The first publishing initiative was already online in early March 2022: The writer Linor Goralik launched ROAR, a website collecting testimonies against war and dictatorship in poetry, prose, essays, and other genres.

A year later in the spring of 2023, a publishing house with the eloquent name Freedom Letters announced its debut with the publication of “texts banned in the Russian Federation.” At present there are about a dozen similar projects that have appeared over the past two years. Emigre poetry almanacs; e-publishing startups of queer literature; bookstores delivering paper editions of authors who are “foreign agents” in Russia.

So has “tamizdat” returned to Russian reality?

Tamizdat – “published there,” a play on samizdat (self-published) — is usually considered to have begun in 1957, when Boris Pasternak’s novel “Doctor Zhivago” was released in Italy. The following year, when the USSR forced Pasternak to renounce the Nobel Prize, the novel was read on Radio Liberty and was given out to Soviet citizens who were abroad.

But philologist and founder of a new tamizdat project, Yakov Klots, believes it is more accurate to say that the phenomenon originated in 1929 when the writers Yevgeny Zamyatin and Boris Pilnyak dared to publish their texts criticizing communist ideas abroad — one in New York, the other in Berlin.

In 1966, two writers, Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, were tried and sent prison for publishing their texts in France. This process marked the start of the dissident movement and the flourishing of tamizdat. Banned books were intended to be read not only by emigrants or Western Slavists; some were smuggled into the USSR.

Ellendea Proffer, co-founder of the American Ardis publishing house, recalled attending a Moscow book fair in 1977 and hiding Nabokov’s “Lolita” during a search. Distribution wasn’t just managed by individual sympathetic enthusiasts. The CIA also got involved in distribution on a much larger scale. Enlightenment became a weapon of the Cold War. The books were specially published in a pocket-sized format to make it easy for journalists, athletes, musicians and (of course) sailors to deliver them. And some shipments were even printed on special waterproof paper and dumped in ports in the hope that the books would land on the Soviet shore. Émigré writer Alexander Genis once told the story of circus performers who hid books in a cage with tigers, where, of course, nobody would enter. They didn’t smuggle just anything — they brought in works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and a batch of Playboy magazines.

Meanwhile, censorship in today’s Russia is not total. People call it “creeping censorship” because it appears here and there and then disappears again. In modern reality, it is not as easy to establish firm control as in the USSR, when the system for several decades was based on the terror of the state that was formed by Stalin’s repressions.

However, by the Brezhnev era this control had taken a very formal and grotesque form. Lev Rubinstein, the legend of uncensored conceptual poetry of the 70s, described this in detail. When one of an author’s works was published in a foreign journal, the writer waited for a call for “the talk” with KGB. During the talk the writer would just insist that he had no idea how his texts had ended up “over there.” The author would be released. The fact that the Western publishers put the phrase “printed without the author’s knowledge” above each publication was enough for KGB, though everyone knew it was a lie.

Today there is no prohibition on the transmission of texts. Now people are put on trial for the content, being accused of “LGBT propaganda,” “extremism,” and “discrediting the army.’’ Besides, it is simple to trace the path of a text transmitted over the Internet.

But the main thing seems to be the difference between the regimes. “Soviet authoritarianism of the 1970s was authoritarianism on the wane, a decrepit authoritarianism,” literary scholar and publisher Dmitry Kuzmin said. “It was interested in paper logic, in some kind of its own Soviet pettifogging. All of this was done without enthusiasm, in a lazy way… [but] today we have authoritarianism gaining momentum.”

In 1929 both Pilnyak and Zamyatin wrote apologetic letters saying that the manuscripts had gone to foreign publishers without their knowledge. Zamyatin had to emigrate to France soon after, and Pilniak was executed in 1938.

The many forms of tamizdat

The word tamizdat appeared in the 1970s, but now it’s harder to define. There is a general consensus that not everything published “over there” (“там”) is tamizdat, but how can it be distinguished from emigrant literature? Klots uses a very elegant and succinct formula: “Tamizdat is a text that has crossed the border at least once.”

But a text published on internet crosses hundreds of borders in an instant. Books no longer need to travel in under the protection of wild animals or in a secret pocket. One click on your computer and an anti-war poem or a story about Putin’s death is where you need it to be.

Meanwhile, physical books are becoming more popular. “It may seem strange, but we think that physical books are more important now, especially for the reader who is outside Russia,” said Alexander Gavrilov, who launched Vidim Books in Latvia a few months ago. Their book covers feature faces of famous emigrants as well as an image of Putin’s face in the grimace of death.

“In the nomatic life we suddenly found ourselves in, you’d think we’d read e-books. But a physical book is the kind of object that is important to us — not just for reading, but in the sense of physical presence,” Gavrilov said. A book in your native language is something you want to keep on the shelf when you’re in a foreign country. And even better if the book describes a similar emigrant experience, contains anti-war essays or tells about a zombie apocalypse in Moscow left behind. The question is: How does this book find its way to that shelf?

“The new emigration has scattered people around the world in so many different directions that the logistics of getting these paper books there is almost impossible task,” said Dmitry Kuzmin, who left Russia after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and launched the project Literature Without Borders. Kuzmin also publishes poetry from Ukraine, “so the revival of the paper book outside Russia seems particularly significant and paradoxical,” he said.

Freedom Letters can be considered the most successful case in point. The managerial efforts of its founder Grigory Urushadze are centered on making production as cheap as possible and sending their products all over the world. The publishing house began as a volunteer project to produce e-books. As Freedom Letters gained momentum, it added paperback books that are printed in small runs in countries all over the world, from the US to Georgia, depending on the specific needs and opportunities. Freedom Letters sells these books in Russian bookstores that have opened in the last two years in Tbilisi, Yerevan, Berlin, Lisbon, and elsewhere. Some are also on the shelves of independent bookstores in Russia, and a few titles were even sold on the largest US domestic marketplace, OZON.

For example, the novel “The Mouse” by Ivan Filippov is a great success. In order to place this product on a Russian site, the publisher needed to make only a few edits to the book annotation. On the Freedom Letters website the text reads that “the Institute of Functional Immortality, where a means to prolong Putin’s life is being developed,” but on the Russian Marketplace it reads that “the Institute of Functional Immortality, where a means to prolong life is being developed.” And in keeping with Russian laws, the Russian annotation is preceded by the so-called “foreign agent’s label” to inform potential readers of the author’s status. They also needed to add the age limit of 18+.

None of this bothered readers. Three printings of “Mouse” sold out in a matter of hours, and a larger fourth printing sold out in a couple of days. The book’s page is full of questions from customers who want to know when it will be available again, although in July the Russian Prosecutor General demanded the book be withdrawn from sale.

Publishers and books around the world

Some of the new emigrant publishers produce books for children; after all, young readers in new countries also need something to put on their physical and metaphysical shelves. “We had a wonderful series called ‘Savior and Son’ about a psychotherapist who works with teenagers,” said Irina Balakhonova, head of a Russian publishing house that now sells some titles through a partner firm called Samtambooks. The book, she continued, “featured non-binary people who self-identified in the process of therapy, but then the ‘law on LGBT propaganda’ happened. It was clear that we couldn’t publish the seventh book of the series and that it wouldn’t be safe to sell the other books in the series in Russia either. But the readers who left — why should they lose the last seventh book of the series and not have the happy ending? So we decided that we would just publish it in Riga and sell the whole series ‘tam’.”

This book was followed by others that cannot be released in Russia at present. At the same time, as a children’s publishing house Samtambooks is mainly focused on paper books, which means that their distribution throughout the world is a key issue.

The small family publishing house Babel with a Russian bookstore of the same name in Tel Aviv is also devoted to selling physical books. Their absolute sales leader was the book cited above by Boris Akunin, who has also started his own publishing business and a platform to help other immigrant publishing startups to sell books banned in Russia.

The second most popular book that Babel published is the prison autofiction “I Wish Ashes On My Home” by activist Daria Serenko. And in third place is a collection of poems from 2022-23 by a poet based in Russia, whom the publishers asked not to name.

The founders of the project, Yevgeny and Lena Kogan, regularly send their books to Russia “by hand.” That is, they print books on demand, take them to the post office and mail them to Russia. Readers form groups to share the shipping fees. The number of books sent this way runs into the hundreds — exactly how many is hard for the publishers to say. More books are brought in suitcases, since despite the wars there is a constant flow of people visiting their relatives and friends. “They come to our store and ask for ‘what you have that isn’t sold in Russia’,” Yevgeny Kogan said. “I show them some books and they say — oh, we’ll take this but probably not that, since we just have hand luggage” (which can be checked at Russian customs).

Right now there are no restrictions on carrying books into Russia and no known cases of books taken away at the border. But, Lena Kogan said, “The difficulty of the situation is its unpredictability. People are constantly in a state of fear and don’t know what could happen.”

Samtambooks, for example, currently has no plans to distribute their books in Russia due to safety concerns. Irina Balakhonova said, “We will publish them for people who are in Europe…we are not going to break the law and send something forbidden to Russia yet. I am the child of a political prisoner. My father was in a Soviet prison for 15 years. I don’t want to be in the same situation. I feel like I already served my time during my childhood…”

However, in the absence of the sponsors that supported this work in the Brezhnev era, tamizdat publishers must sell books, both paper and electronic, to survive. This immediately cuts off most Russian readers, because international sanctions do not permit paying for purchases with a Russian bank card on foreign sites.

Publishers are trying to find a way around this. For example, the e-project Papier-Mache offers to pay for texts through Boosty, the Russian analog of the Patreon service. Freedom Letters transfers a Russian client to a special Telegram bot where purchasers can buy a set of stickers and receive any book “as a gift.” But these methods do not always work properly and in general are intended for the rare, very motivated reader.

Meduza, a publishing house affiliated with the well-known Russian-language independent media outlet Meduza, solves the payment problem by making their books — mainly collections of journalistic articles or books written by journalists — available free of charge. ROAR creator Linor Goralik has also made her novel “Bobo the Elephant” available to the public for free. Goralik’s novel, set in 2022, was supposed to be released in Russia, but at the last minute the author decided not to jeopardize “the brave employees of the publishing house.” However, Goralik’s website, like Meduza’s, is blocked by the Russian authorities, only accessible to people with VPNs.

So despite all the technological differences, the current situation is much the same as it was in the Soviet era. To get a tamizdat book, you have to make some effort and, as they said in the Soviet Union, “to know where to go.”

Inside Russia

But there is one very important difference today: there is nothing even close to the book hunger described by Ellendea Proffer in her memoir “Brodsky Among Us”: “…people standing in line for two hours or more to get into a small booth where they had heard there might be interesting books on display. Readers from all over the Soviet Union made their way to these fairs, and some of them didn’t seem like literary readers at all — and these were in a way the most interesting visitors. The intellectuals pushed over to the Nabokov titles and tried to read an entire novel standing, but the working-class/peasant sort of visitors didn’t care or know about Nabokov: they went immediately to the biography of Esenin, which featured many photographs, including one never reproduced in the Soviet Union, that of Esenin after his suicide. This biography of the people’s poet was in English, but everyone recognized Esenin’s face on the cover.”

Whether the Russian Federation will eventually try to become a completely closed state is a big question. “When they [Russian authorities] began to say that we will now completely close the borders, we will now completely make the cultural space opaque, and so on — they are just lying and sticking out their chests, just like they always do,” Gavrilov said. “Closing the intellectual and cultural space turned out to be no easier than ‘taking Kyiv in three days’.”

No one knows how long the status quo will last and what the authors of contemporary tamizdat living in Russia risk. Perhaps there will be a demonstrative precedent of creeping repressions to frighten others, as in the theater community with the case of Yevgenia Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk, now serving jail sentences for their play about women recruited by ISIS. It’s hard to say whether such a trial of any writer will lead to an increase in the number of anonymous publications or a complete refusal to deal with the emigrant publishing houses.

The publishing houses are determined to continue their work, which they view as part of the ideological and political struggle, very much like their forerunners. Gavrilov’s publishing house intends to try not only to sell, but also to print in Russia their books that do not yet break any laws.

It is strange that if these plans come true, in some symbolic sense these books will still remain tamizdat books, although they will, in fact, be created not “there” but “here.” This was impossible during the Soviet era, and perhaps the word tamizdat should be retired. Books like this might be called “Internetizdat” or perhaps “netamizdat” (not-published there). Or perhaps it would be best to at least separate the eras and refer to current practices as “new tamizdat.”

Perhaps the persistence of the term “tamizdat” is a sign that the essence of the phenomenon has not changed. During a customs search at the Russian border, they won’t examine your coat lining, but they’ll check your electronic devices. In Moscow to buy a banned book you don’t seek out an underground book dealer, you look for one you can purchase online. Publishers don’t use expensive waterproof paper; they just publish books with AI covers.

In the end, none of these differences really matter. There is a feeling that the Soviet era never ended, and that means that the tradition of tamizdat did not end either. “We lived in this illusion of freedom that we had created ourselves,” Lena Kogan said, “In the 90s we thought the old system had collapsed and that we were living in another country. But now it’s clear that this system did not become history. It continues to exist and grind people to dust.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Once

Monthly

Annual

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.