One of the most important Slavic folk holidays is Святки (holy days) which in the West are called the “twelve days of Christmas.” In Russian these days are said to stretch “from the star to the water,” that is, from the appearance of the first star on Christmas Eve to baptism on Epiphany. This is the most fabulous and magical time of the year: fortune-telling, carols and charms intoned for good fortune. And today, without even realizing it, just like a thousand years ago we believe in the evil eye, evil forces, good fairy tales and good fortune.

Children still believe in fairy tales, but adults do not. But this is a terrible mistake! In some matters fairy tales do not lie at all. For example, in food. Fairy tales preserve for us forgotten dishes, products and customs.

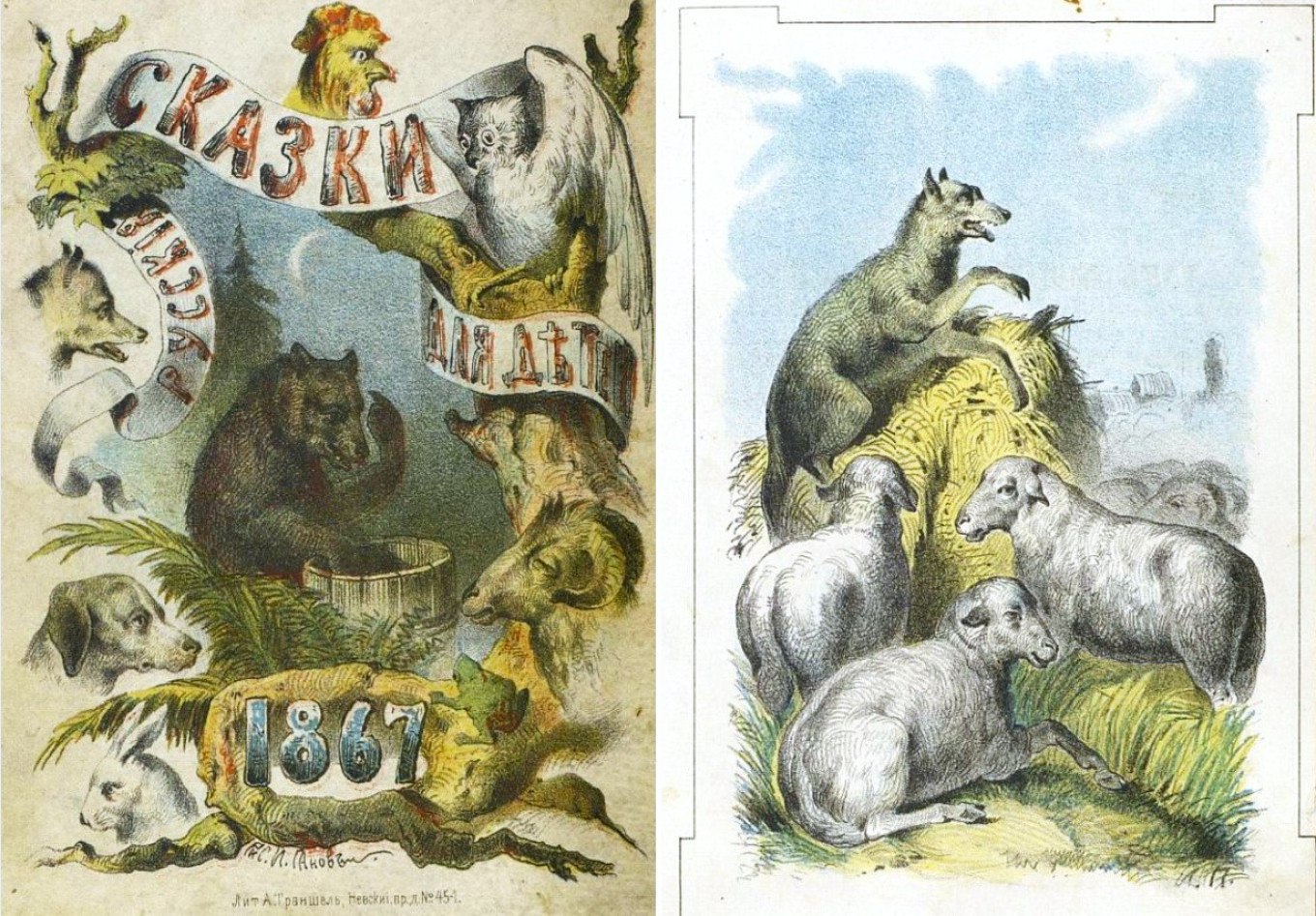

Here’s something few people know: Russian fairy tales and cooking have a lot in common. “Kolobok,” “The Wolf and the Goat,” “The Cat, the Fox and the Rooster” are the great classics of Russian children’s literature. But how many of you have wondered where they came from?

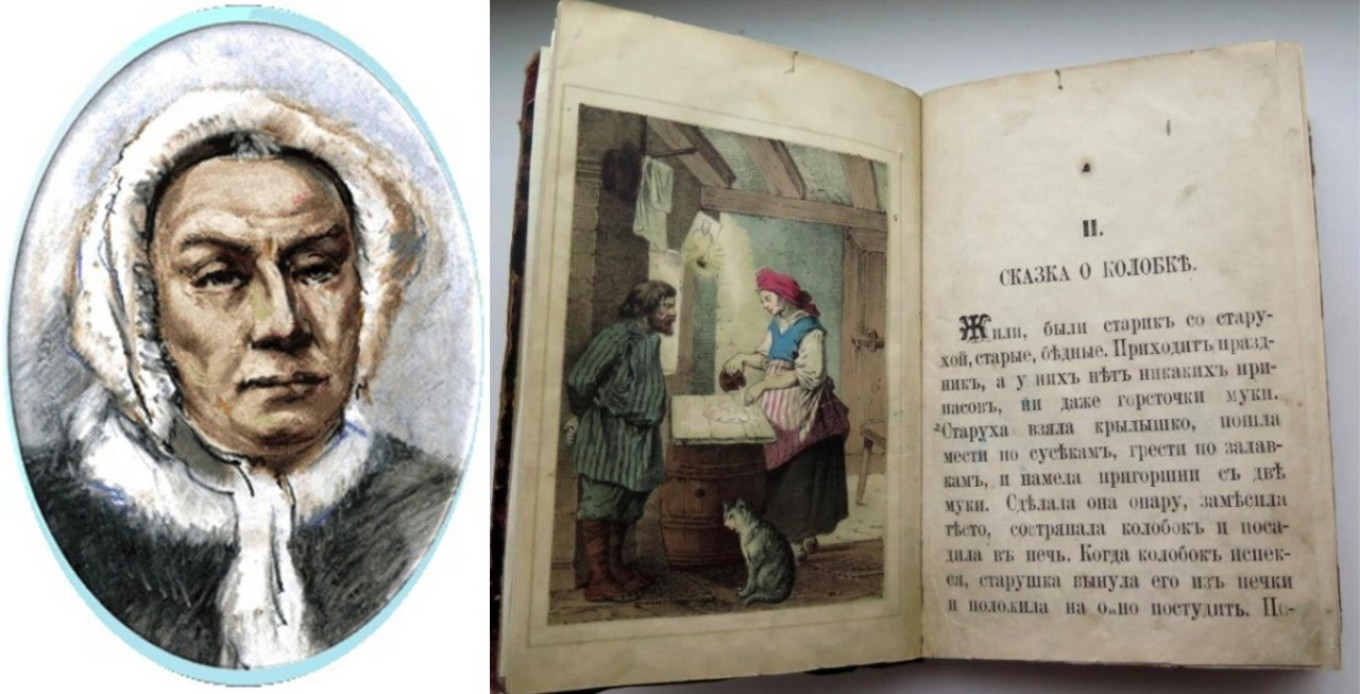

It turns out that they were written by Yekaterina Avdeyeva, one of the founding mothers of Russian cuisine. She was the first woman to publish a cookbook in Russia. But in addition to her talents as a cook, she is credited with preserving fairy tales. They were first collected in her book “Russian Fairy Tales for Children, Told by Nanny Avdotya Stepanovna Cherepeva” (St. Petersburg, 1844).

It’s actually not at all strange that a cook was fascinated by fairy tales. After all, folk legends and tales often preserved the old, traditional household customs. For example, we read that most animals are named in fairy tales. A hare is a hare, a crow is a crow, and a fox is a fox.

But in Russian folklore there is one animal that writers and people try not to name: the bear. For superstitious reasons our ancient ancestors made up all sorts of “substitute” names to refer to the bear, like Mikhailo Potapych, Toptygin (“Tramper”) or Kosolapy (“Splay-footed”). And the Russian word for bear — медведь — is also a euphemism. We don’t know the “real” name of this creature; that was dangerous to say out loud. Now he is just referred to as the “honey eater” — мёд едящий or мёдоед.

Another example is the wolf. Have you ever wondered why our fairy tales have such a dislike for him? It’s simple. For our distant ancestors, the wolf was not so much a threat to humans as to domestic animals. In ancient Russia the wolf really posed a great danger to the small herds of cows and sheep. So even children had to know that if the wolf attacked the family would be without milk, delicious pies and even sour cream for soup.

But the fox was sometimes admired for its cunning. The fox could even trick the nimble Kolobok (a round bread roll). By the way, we believe that the kolobok is indigenous to Russia. But this fairy tale is popular in many countries, and it’s found in virtually all through the Indo-European world, although of course it has different names. For example, in one part of the world there is a rolling lavash. And almost all cultures have a baked bread as a fairy tale hero. But if we look in our old cookbooks, such as “Russian Cookery” (1795-98) by Vasily Lyovshin, we find “colobo pie.” In this cookbook it’s a round roll filled with minced beef, onions and peppers — something the fox would have liked much better than the plan dough Kolobok.

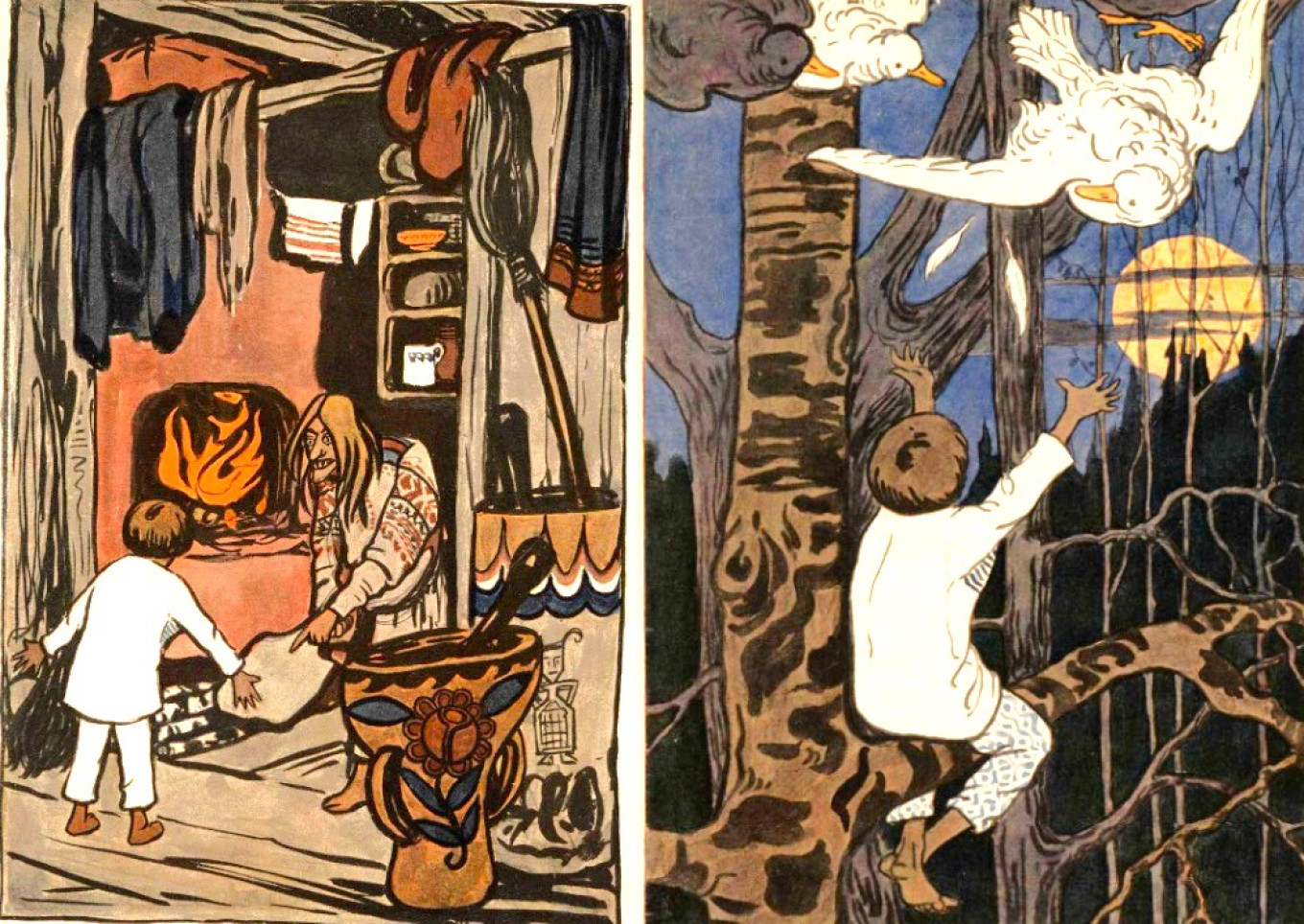

Modern fairy tales almost always end “happily ever after.” But in the past they were scary stories. “Come here, Ivanushka, I’m going to heat the stove today, I’ll put you in the stove, you’ll taste better. Hop on the shovel!” says the witch Baba Yaga. What a horrible image — lifting a child on a shovel and putting him in the oven! Who could think of such a thing? Actually 200 years ago it was quite a common practice — not culinary, but therapeutic. Small newborn babies were sometimes put in the oven — almost cooled, of course — to warm them up. Why? In a Russian oven there was warmth and healthy, sterile air. It was a good place for them to move their arms and legs, so that they would grow strong and healthy.

Fairy tales also included some interesting culinary information, too. What is it that “flowed down a moustache, but did not get into the mouth”? Honey? What did it taste like?

Of course, it’s not today’s honey, it’s a honey-based drink that used to be called “fermented honey.” It was similar to mead: honey was diluted with water or berry juice and spices and herbs were added. And then it was poured into a barrel, fermented for a long time and then kept for an even longer time before drinking. When a child was born it was not uncommon for the father to bury a barrel of mead in the vegetable garden only to dig it up on his son’s wedding day. That was when the real party began.

Or take the famous fairy tale “The Swan-Goose.” In one passage the river hides a fleeing girl under its “kisel shores.” Readers today see the word “kisel” and imagine something liquid that is poured into a glass. But ancient kisel was not drunk, but eaten. It was really dense with a consistency like jelly — which made firm “kisel shores” in fairy tales. It was made from bran, oats, rye, and peas, which were covered with water and allowed to stand. This water was changed several times (the source of the fairy tale expression “the seventh water on kisel”). Basically starch was washed out of flour, allowed to swell up with water, ferment slightly and then brewed.

The fabled turnip gives us a whole set of culinary associations. First, we see our custom of growing vegetables until they are completely ripe. The bigger the turnip, the better — so big that the cat and mouse would have to be enlisted to help pull it out of the ground. In some ways this made sense. Russia doesn’t have a Mediterranean climate, and the milky savoriness of artichokes or patty pan squash would not be appreciated. Russian cuisine is all about boiling and baking vegetables, so the flavor was less important than the size.

Secondly, it’s the turnip itself. Before the advent of potatoes, the turnip was “our everything.” You could chop it up and add to soup or chowders. It went into a dish that is forgotten today called ushnoe that was something like a modern stew with vegetables, turnips and meat that were stewed together in the oven. This fragrant dish was one of our ancestors’ favorites.

In general, in fairy tales, everything is equally balanced — feasts in rich houses and a poor hut where they scraped the bottom of the barrel. We like to talk about the rich feasts in fairy tales just because, well, they are fairy tales. We should never think that the enormous variety of recipes in Russian cuisine was the real menu of an ordinary person. “Domostroi” (1550s) mentions about 130 dishes. But in real life an ordinary person had thin cabbage soup, plain porridge, bread with purslane — and rarely meat on the table. That’s why there were fairy tales with tables heavily laden with rich food. That’s what people dreamed of. Why not? It’s a lovely dream, isn’t it?

Here’s a simple soup made with foraged and then dried mushrooms (porcini) and home-made noodles. A simple dish fit for a fairy tale king.

Porcini Noodle Soup

Ingredients

For soup:

- 50 g ( 1 ¾ oz) dried porcini mushrooms

- 1 medium carrot

- 1 medium onion

- 3 small potatoes

- 2 Tbsp vegetable oil

- salt to taste

- herbs for garnish

For noodles:

- 300 g (10.6 oz or 1¾ cups + 2 Tbsp) flour

- 130 ml (1/2 c) cold water

- 1 tsp vegetable oil

- 1/2 tsp salt

Instructions

- Prepare the noodles. Mix the flour with the salt and then pour in the water and vegetable oil. Knead the dough. It is not necessary to try to knead the dough until it is smooth right away. Just form it into a ball, put it in a plastic bag, and leave it for 40-60 minutes. During that time knead it twice. By the end of the hour the dough will be completely smooth.

- Roll out the dough into a 2 mm (about 1/10 of an inch) circle. The dough shouldn’t be too thin; otherwise the noodles will lack flavor. Leave it to dry on the table or, even better, hang it up. For example, put a towel over the back of a kitchen chair and lay the dough over it.

- Soak dry porcini mushrooms in cold water for 20 minutes. Then drain the water and rinse the mushrooms. Pour cold water over them again and leave for 1 hour.

- Sprinkle the noodle dough with flour, cut into two halves and form each half into a roll.

- Cut the noodles with a sharp knife and leave on the board. Handle the cut noodles carefully so that they don’t stick together. Make sure the dough is dry and floured.

- Take the mushrooms out of the water and cut into smaller pieces.

- Carefully drain the water in which the mushrooms were soaked into a pot for cooking. There may still be sand at the bottom of the bowl.

- Add up to 2 liters (approximately 2 quarts) of water to the pot, add the mushrooms and bring to a boil.

- Remove the foam, reduce the heat and cook over low heat for 20-25 minutes. Salt the mushroom broth to taste.

- Dice the onions and potatoes, julienne the carrots and sauté them in vegetable oil until golden.

- Add the sauteed onions, potatoes and carrots to the mushroom broth. Boil for 8-10 minutes.

- Shake as much flour as possible off the cut noodles and drop them into the broth with the mushrooms. Bring to a boil and simmer for 2-3 minutes.

- Let the soup rest for 10 minutes and serve with your favorite garnish.

To make the broth perfectly clear, put the noodles in a colander and drop them into the boiling water for a few seconds and then immediately add them to the broth.

… we have a small favor to ask.

As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

It’s quick to set up, and you can be confident that you’re making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.