Humans are embodied like all other animals, but according to Plato we are distinguished from the beasts through our possession of a sacred attribute: reason. This attribute is manifest in our ability to contemplate the nature of reality and reflect on how we ought to act. Thinkers from Plato to Steven Pinker have placed great faith in our capacity to overcome our savagery and create a better world through the exercise of divine rationality.

In a powerful and startling series of paintings that make up the Pushkin Museum’s School of London exhibit, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and several of their 20th century contemporaries question the potency of our rationality by focusing on the bodily nature of our existence. Specifically, Bacon, Freud, and their colleagues push back against Plato and Pinker’s utopian vision of reason through an open and honest study of our animated bodies, our gnawing anxieties, and our unspeakable atrocities.

The exhibition begins innocently enough with a wedding-day portrait of the painter, R.B. Kitaj, his wife Sarah Fisher, and several artists who were part of the so-called School of London. Kitaj himself came up with the School of London moniker when he curated a controversial exhibit at the Hayward Gallery in 1976. In that show, Kitaj displayed the work of Leon Kossoff, Michael Andrews and other figurative painters who were keen to challenge the abstract art dominant at the time, and the dancing characters in Kitay’s colorful “The Wedding” exemplify the attention paid to the human body in the rest of the Pushkin Museum’s exhibit.

A lively and teeming mass of humanity is the subject of Kossoff’s most celebrated work in the Moscow show: “Children’s Swimming Pool.” Kossoff spent several seasons at the Willesden Sports Center in London teaching his children how to swim, and the pool was the subject of numerous paintings and sketches that now reside in some of the U.K.’s most prestigious galleries. The bright colors and energetic atmosphere of Children’s Swimming Pool illustrate the fun to be had at a public pool on a warm Sunday afternoon. Yet mania and the sheer amount of flesh on display conjures a certain amount of angst, and viewers ought to be forgiven if the scene reminds them of modern-day factory farming.

For every bit as hectic and public as “Children’s Swimming Pool” is, Michael Andrews’ “Melanie and Me Swimming” is quiet and private. This life-size painting was based on a photograph taken by Michael’s friend, Jean Cornet, when Michael and his family were vacationing in Scotland. The painting itself depicts Michael supporting and stabilizing his daughter as she splashes and swims away. It clearly captures an intimate moment of love and affection, but the painting is also imbued with an existential weight that is indicated by the black surroundings and the vulnerability of Michael’s daughter, Melanie.

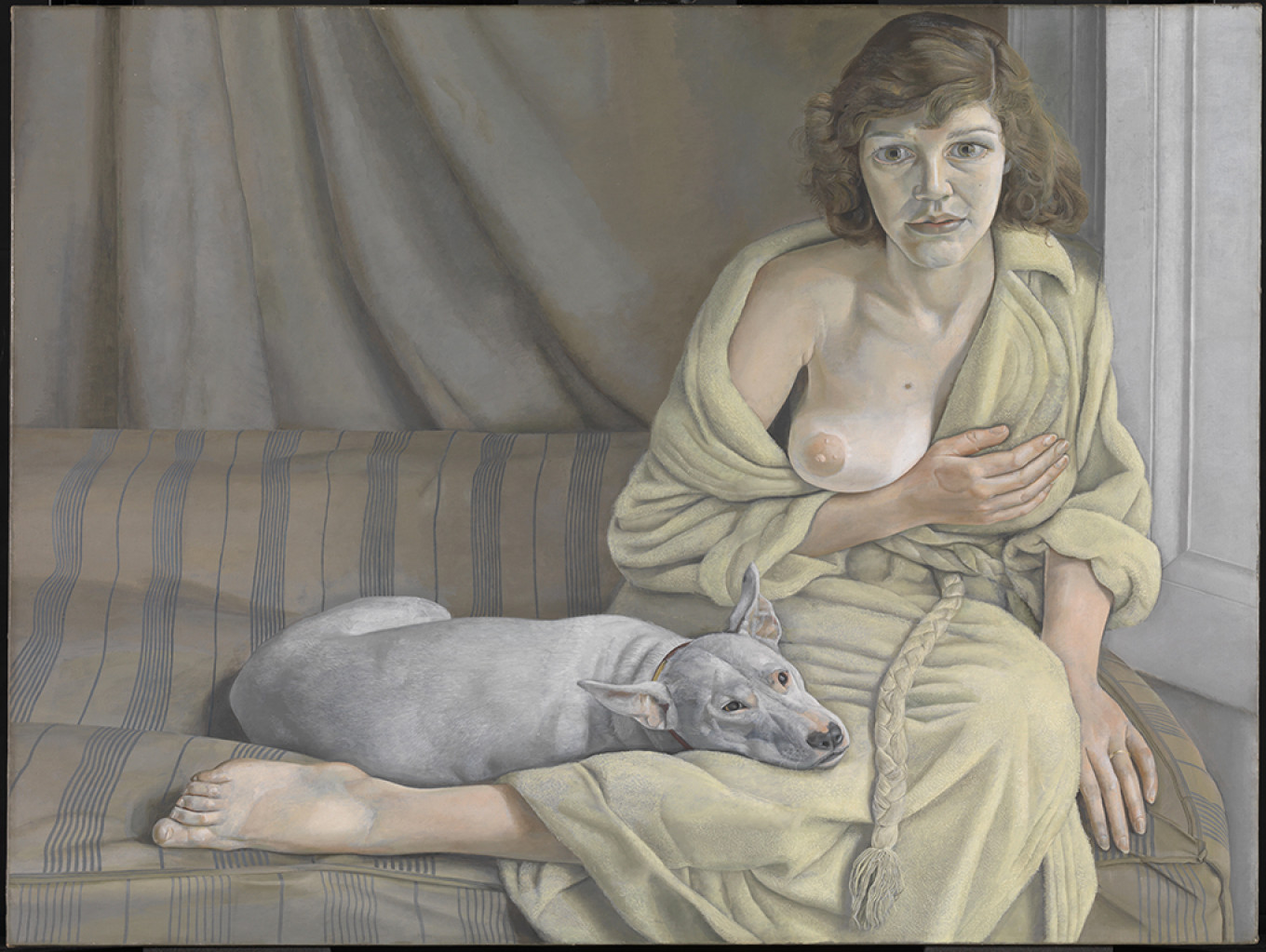

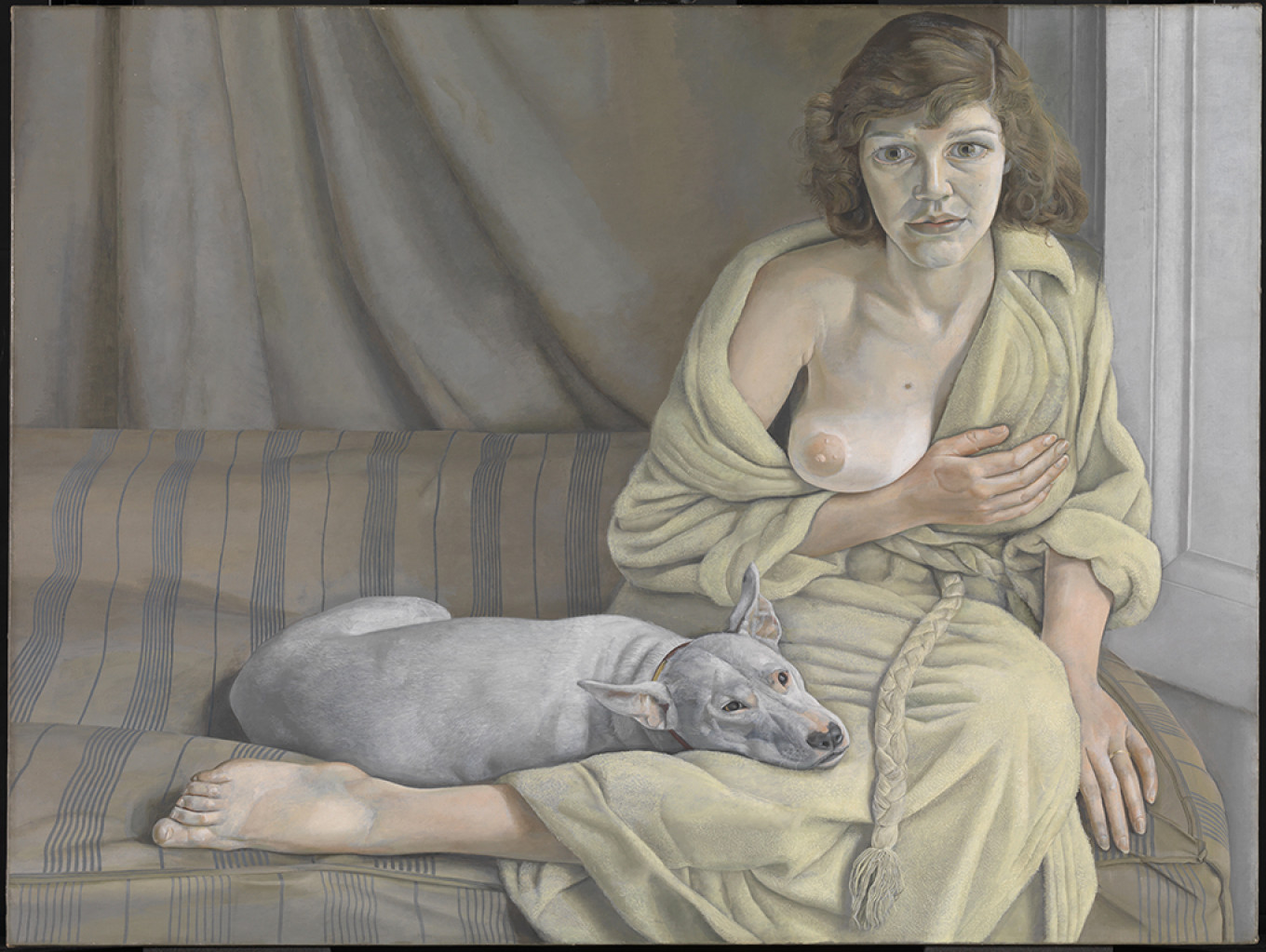

Intimacy and vulnerability characterize Lucian Freud’s 1950-51 masterpiece, “Girl With a White Dog,” and this painting alone is worth taking a rush-hour metro to the Pushkin Museum. In the portrait, Freud’s first wife, Kitty Garman, is sitting upright on a couch with a white dog resting its snout in her lap. She is wearing a pale-green dressing gown and one of her breasts is exposed whilst the other is covered up by her hand and the edge of the gown.

Stylistically, “Girl with a White Dog” exhibits the clean lines and meticulous detail found in the art of the French Neoclassicist, jean Ingres, but Freud avoids the idealized body typical of Ingres’ work. Indeed, the hesitant expression on Kitty’s face, along with the vulnerability of her exposed breast and the imperfections in her figure, suggest both the openness and anxiety one might expect if she were about to sit down with Lucian’s grandfather: Sigmund Freud. Alas, Lucian’s work never explores the dark reaches of the human psyche, and he leaves an analysis of the horror of human existence to the star of the School of London show: Francis Bacon.

Famous for his paintings of disfigured bodies and screaming Popes, Bacon came of age as an artist during the Second World War and his signature style emerged just as images of the Nazi terrors were surfacing in England. In his 1945 portrait “Figure in a Landscape,” Bacon presents his lover, Eric Hall, snoozing on a park bench. However, much of Eric’s body is distorted or painted-over such that the viewer is drawn to a black void in the middle of the portrait. Bacon’s lover also appears to be holding a microphone reminiscent of those used by Nazi leaders when they were delivering their speeches, and Bacon is clearly calling attention to the barbarity of calculated political violence. Indeed, far from being endowed with divine rationality that distinguishes us from the beasts, Bacon’s paintings show us just how savage the exercise of reason can be.

This theme is taken to the extreme in the centerpiece of the School of London exhibit: namely, the second version of Bacon’s 1944 “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.” Here we are presented with a series of fleshy, disjointed, and screeching demons that stand out from a blood-red background. The implication seems to be that we have killed off the utopian fantasy of a benevolent god within us. And if anything, the atrocities of World War II teach us that our embodied existence is demonic.

Perhaps this is hyperbolic. But still, everyone ought to make their way to the Pushkin Museum’s all too human School of London exhibit before it closes on May 19.

12 Ultisa Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. pushkinmuseum.art

For more insight into this show, read an interview about organizing the show with the head of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Marina Loshak here.