The once-Russian, now-American artists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid got together to look back over the art they created as a team, the places they lived and the times they lived through. The occasion for this was a retrospective of their work held at the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers University in the U.S. The show followed their path from their earliest work together in the 1970s until they stopped collaborating in 2003, along with works they each created later.

It was a wild ride. Over the years the two artists created paintings in every conceivable style and genre. They worked in photography and performance art. They created installations, sculptures, an opera, music and poetry. They made letter-writing an art form. And they collaborated with other artists as well as with creatures, great and small.

Komar and Melamid began to work together in Moscow after graduation from the Stroganov School of Art and Design in 1967. In 1972 they created Sots Art, a kind of mash-up of Soviet Socialist Realism and Western Pop Art. These were meticulously painted canvases with inappropriate images — their portraits in profile, like Lenin and Stalin — or familiar appeals (“Our Goal is Communism”) made ridiculous by the signature of the artists, or an “Ideal Slogan”— a line of squares instead of letters followed by the obligatory exclamation mark.

That was just the beginning. The pair set out to come up with at least four original projects a year. One was a set of Biographies that included the (supposedly) first abstract paintings done by a fictional serf artist named Apelles Ziablov and dozens of sentimental images of a landscape done by the (also fictional) one-eyed artist Nikolai Buchumov, each with a bit of the artist’s nose in the corner (the bane of a one-eyed artist’s vision). These were presented deadpan, with biographical information.

They also created a groundbreaking work called “Biography of Our Contemporary” — 197 two-inch tiles, each painted in a different style, each depicting part of life in a line from conception to emigration.

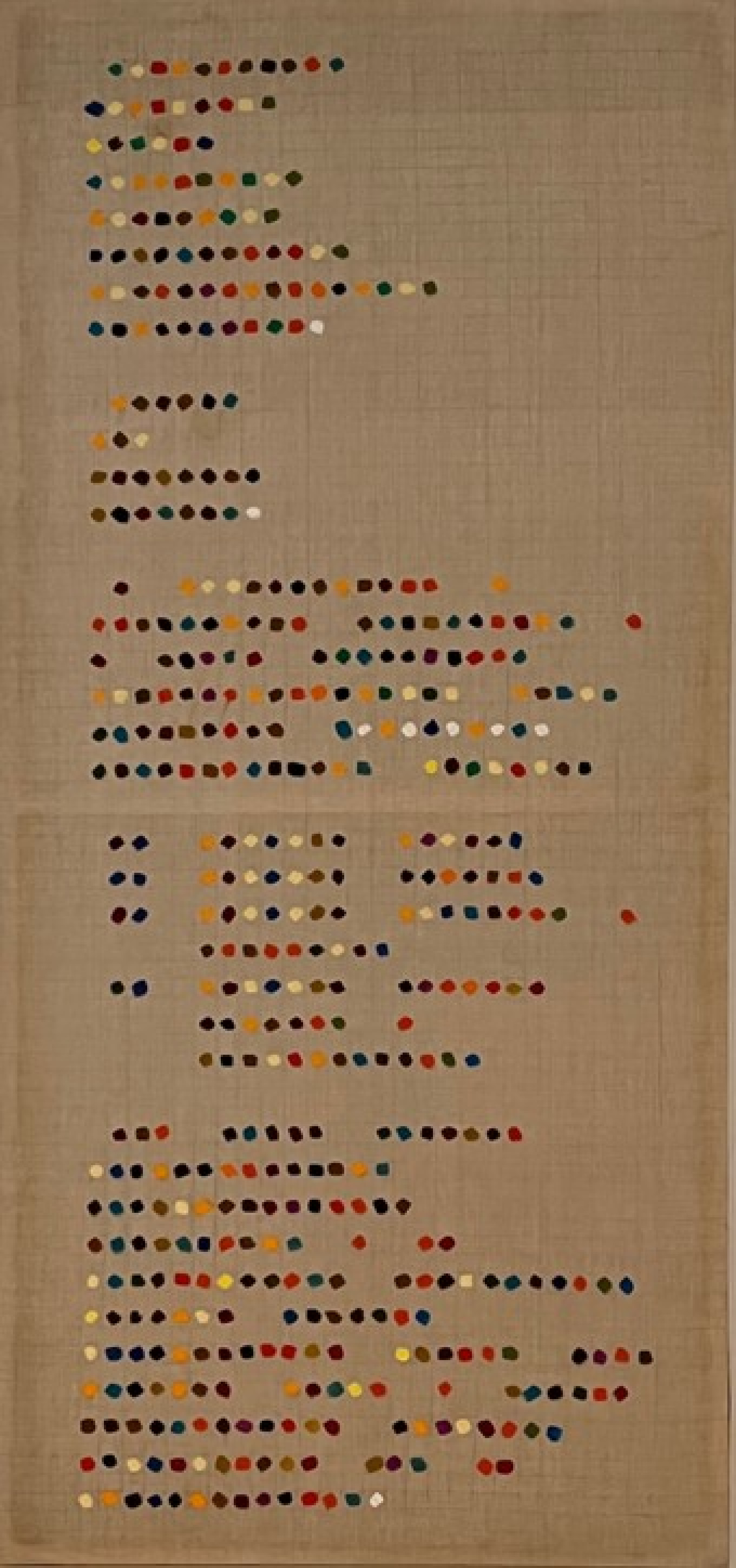

Then came Post Art — art of the future — including the iconic “Factory for the Production of Blue Smoke.” They made a series of coded works (an essential skill of Soviet people) that included the story of their lives in a language they invented (and later forgot) and a canvas with colored dots that represented letters in an excerpt from Soviet Constitution. That became particularly famous when border guards thought it was a tablecloth and let it through customs.

They also produced a series of canvases with a few tiny, brightly colored brush marks in the center, which upon closer look appear to be miniscule figures representing key moments in Russian history, such as “Conference regarding the best and quickest ways to subjugate the Khazan Khanate, April 1552. Fourteen people present.”

These works were created in the Soviet Union. It is no surprise that the powers-that-be in Moscow were not amused. Komar and Melamid were arrested in 1974 for an apartment performance, and their Sots Art double portrait was smashed in the so-called “Bulldozer Exhibition,” when the authorities destroyed an outdoor show of unofficial art.

If the Soviet authorities were displeased, the New York art world was ecstatic. In 1976 the Ronald Feldman Fine Arts gallery in New York held a show of their works that had been smuggled out of the country by various means. The two artists were not given visas to attend. That was the pretext for another Komar and Melamid project, Trans State, the creation of a kind of sovereign nation-in-limbo complete with insignia and passports. They were finally granted permission to emigrate to Israel in 1977, and by 1978 they were working together in New York.

In the U.S. they bought and sold souls, including the soul of Andy Warhol, under the slogan “No one else in the world pays cash for nothing.” They joined together American advertising and Soviet propaganda posters in a series called “Glories.” And in 1982 they began the series Nostalgic Soviet Realism, what they called “the dark paintings” that seem to cast a spell on viewers. The works are very large, beautifully painted versions of socialist-realist canvases that look almost — just for half a moment — like works that could have been painted 60 years ago. But as you turn away you suddenly feel as if you’ve done something terribly shameful.

Komar and Melamid left their black magic behind and began to work in what they called Anarchistic Synthesism, something of an expansion of their work on “Biography of Our Contemporary,” only now they used large blocks of various styles and genres. From there – collaborations with animals, including a chimpanzee who took photographs on Red Square and elephants in Thailand who painted with various appendages. Their last collaboration was the series People’s Choice: paintings created to represent the people’s preferences of what they like best in works of art.

And that list is not all the projects that they did or that were represented at their retrospective at the Zimmerli Art Museum. The show was curated by Julia Tulovsky, who had an eye for their best work and a magical gift of keeping the show from being overwhelming. She told The Moscow Times that she had long wanted to do a retrospective of their works, and then “when the war broke out, the relevance of their art to today’s world became of course much more apparent. I had to considerably rethink the concept of the show and the name. It first was called “You are feeling good!” and now it is “A Lesson in History.”

Around the walls of the rooms are quotes from some of the early art critics writing in the US, most of whom seemed to see mostly satire in Komar and Melamid’s works. The humor and satirical elements of their art, Tulovsky said, made some critics find them superficial. But that is a misunderstanding. “They introduced a new and very influential method that is widely used today,” she said. “They call it ‘conceptual eclectics,’ which allows the inclusion of contradictory life phenomena in the same work, helping the viewer to have a new, often tongue-in-cheek perspective on politics, art and other topics. They made a very important contribution to the development of contemporary arts.”

MT talked with Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid about their art, their history and the history of art. The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

MT: Everyone struggles to describe your work. How should I describe you? What do you prefer?

Vitaly Komar (VK): I don’t argue with any perception of our work. I respect the freedom of the viewer to understand it as they wish… the problem is really very simple. When a person begins to talk about art — when a person speaks or writes or discusses art the way we are now, they fall into the role of translator — translator from one language to another. From visual language to verbal language. This is far more difficult than, say, translating verse by the Russian poet Khlebnikov into English… it’s almost impossible because there will always be some subjective, personal understanding. There isn’t an objective translation from visual into verbal language.”

Alexander Melamid (AM): We have never had, and I still don’t have any, let’s say “style.” I don’t understand what the style is….

We are part of the huge picture which is called art. And art consists of drawers or shelves…. We’re open to any interpretation… There’s no right interpretation. There are just different interpretations… And everything is all right. There’s no wrong interpretation.

Back in Russia they see us as Russian — but actually they see us as Russian everywhere… Once when I’d been living in New York for a very long time, I met a friend, a native New Yorker, and she said, “Oh, you got new shoes…They’re so Russian.” “Come on. I bought them at the corner store,” I said. She said, “No, no. Only a Russian could buy these shoes.” I was really amazed. I walked around and I realized that every second man on the street was wearing shoes exactly like that.

You see, if you see Russianism, you see everything as Russian. What does it mean? Why is it Russian specifically? That’s the shelf or whatever, a drawer in which we were placed. And there’s nothing you can do about that.

MT: Could you talk a bit about how you started out in Moscow. You were part of the underground scene, weren’t you?

AM: Generally speaking, yes, but not really. Nobody took us seriously. Nobody. We made our art and then we started to knock on the doors of famous underground artists just out of the blue saying, “Here we are.” People accepted us, but already established figures like Ilya Kabakov or Oscar Rabin thought of us as just funny guys who made a kind of kapustnik — like an amateur comedy gag. That’s how they saw us.

The underground art world was as strictly guarded as the official art world, the Union of Artists, and so on. They didn’t let just anyone in…they were really very guarded — all the privileges, the connections with foreigners, the possibility of sales. It was an alternative world, which was quite well off, quite prosperous, actually.

MT: Looking back, what do you think of your earliest works?

VK: [When starting out] Melamid and I did what are called polyptychs. We combined paintings of various styles depending on our mood. We combined them into something like little streets. In diptychs, triptychs and so on. This was an interesting innovation, I thought.

Picasso changed his style. But he never made diptychs or triptychs from his various styles. He didn’t combine cubism and neo-classicism. Or he didn’t combine, say, his blue period and rose period with cubism. Never in the form of a triptych or diptych.

I think we were the first to do that in the early 1970s. We created a work in 1973 made up of more than 100 little paintings.

AM: Andy Warhol said that every artist is famous for 15 minutes. I want to say more. Every artist is a genius for 15 minutes. I saw this when I looked more closely at some artists who I really don’t like or care about. But sometimes there was something that was really amazingly good.

That’s what is represented by our very early works. Just the beginning, the first 10 years. We were geniuses then… the “dark paintings” were the end of the period. It was, say, from the end of 1972 until 1983.

MT: Could you talk about politics and art and art today?

VK: During war, “the muses fall silent.” War is not a good time for art.

It’s fairly new to have politics in art. One of the first to do it was Goya in the early 19th century. He was the first; he painted Napoleon’s troops executing Spanish patriots in “The Third of May 1808.” But the thing is, politics are history for an instant. It is an instant of history — today, right now.

[In the arts] things are very different than they were all through history. In the past, there was always one style [per age]… the style during the Renaissance, for example… and then for the first time in the 20th century, or even the late 19th, there were different styles in fashion at the same time…. The peaceful coexistence of many different styles had never happened before in the history of art… Eclecticism became a kind of synthesis. This is a totally new phenomenon, and it has changed the idea of progress in art history.

Today artists think less about experimentation since all the options, all the experiments, have been done, all the possibilities of visual style have been used. You won’t amaze someone with abstract art or a performance.

Now the main sensation are the prices at auctions. Art journals write about that. It’s the big sensation. This is the commercialization of the art world.

AM: Art is [sometimes thought of as] a sacred thing. When you talk to some people, let’s say rather simple people, and they ask you, “What do you do?” I say, “I’m an artist.” “Oh, oh, oh!” I cannot explain it, but they know that it’s a privileged caste.

But there’s now, I think, millions of artists who work around the globe… There’s a children’s art, there’s this art, that art. There are millions and millions of people involved. And you try to see more. And when you see more, each one gets smaller. Because there is only so much that we can keep in our mind. The bigger art is, the smaller the artist. And that’s inevitable, I suppose. So that’s how it is. That’s how it works. Of course, it’s not fair, but what is fairness?

The exhibition “Komar and Melamid in America” will open at the Zimmerli Art Museum on Sept. 13, 2023, and run until Feb. 4, 2024. You can read more about the exhibition here.

A book and catalog of the exhibition “Komar and Melamid: A Lesson in History” is available here.