Passerby, a new exhibition at Garage museum, presents a visual and social history of the humble shop mannequin. This mass-produced everyday object is revealed to be a surprisingly rich social phenomenon; the clothes mannequin is, on one hand, a disposable life-sized coat hanger, but in Passerby it is reimagined as an art object, a human sculpture, an underlying idealized body ready to be draped, displayed and made receptive for the projection of any number of fantasies and fears.

As Lucy McKenzie, one half of the artistic duo behind the show explains, for her “the mannequin is a fascinating thing because it embodies such accelerated ideas of trends in female representation. The way that mannequins change over time is just a pure representation of how trends change over the decades, so mannequins are useful as one of the purest examples of a capitalist body.”

The exhibition is the result of a two-year research project by McKenzie and fashion designer Beca Lipscombe, who founded the conceptual clothes brand Atelier E.B. In 2007. Passerby combines their research on fashion history, artistic practice and practical concern with selling clothes, all coming together to illuminate facets of fashion’s hidden histories. Amongst the displays are historic examples of mannequins which are — quite literally — works of art. These include a 1923 design by German sculptor Rudolf Belling, a lacquered silver structure where the human body is streamlined and abstracted into the smooth lines of stylized modernism. It’s a shop dummy which looks like it belongs in a sculpture garden.

Darker dimensions of window displays are also explored here, as in the section devoted to the career of Sasha Morgenthaler, a pioneering Swiss doll and mannequin-maker active from the 1940s-80s. Two of her hand-made, commercial mannequins are seated on a pedestal and spot-lit as if artworks. Far from the perfectly coiffed and curated fantasy which they were designed to sell, they are stripped and spoiled with age, with matted hair and broken disjoined bodies gruesomely pocked and scratched. Their uncanny not-quite-human quality turns them into figures of horror.

Passerby is not merely a visual history of window dressing, however; it also explores how aspects of display continue to shape consumerism today. This is particularly relevant now, McKenzie explains, because while mannequins have been central to how we encounter and consume fashion for centuries, now that “physical retail is in crisis” as shoppers increasingly move online, they are on their way to becoming defunct. To tease out some of the social implications revealed by today’s changing trends, Lipscombe and McKenzie invited several contemporary artists to create new mannequins for Atelier E.B.’s fashion collections.

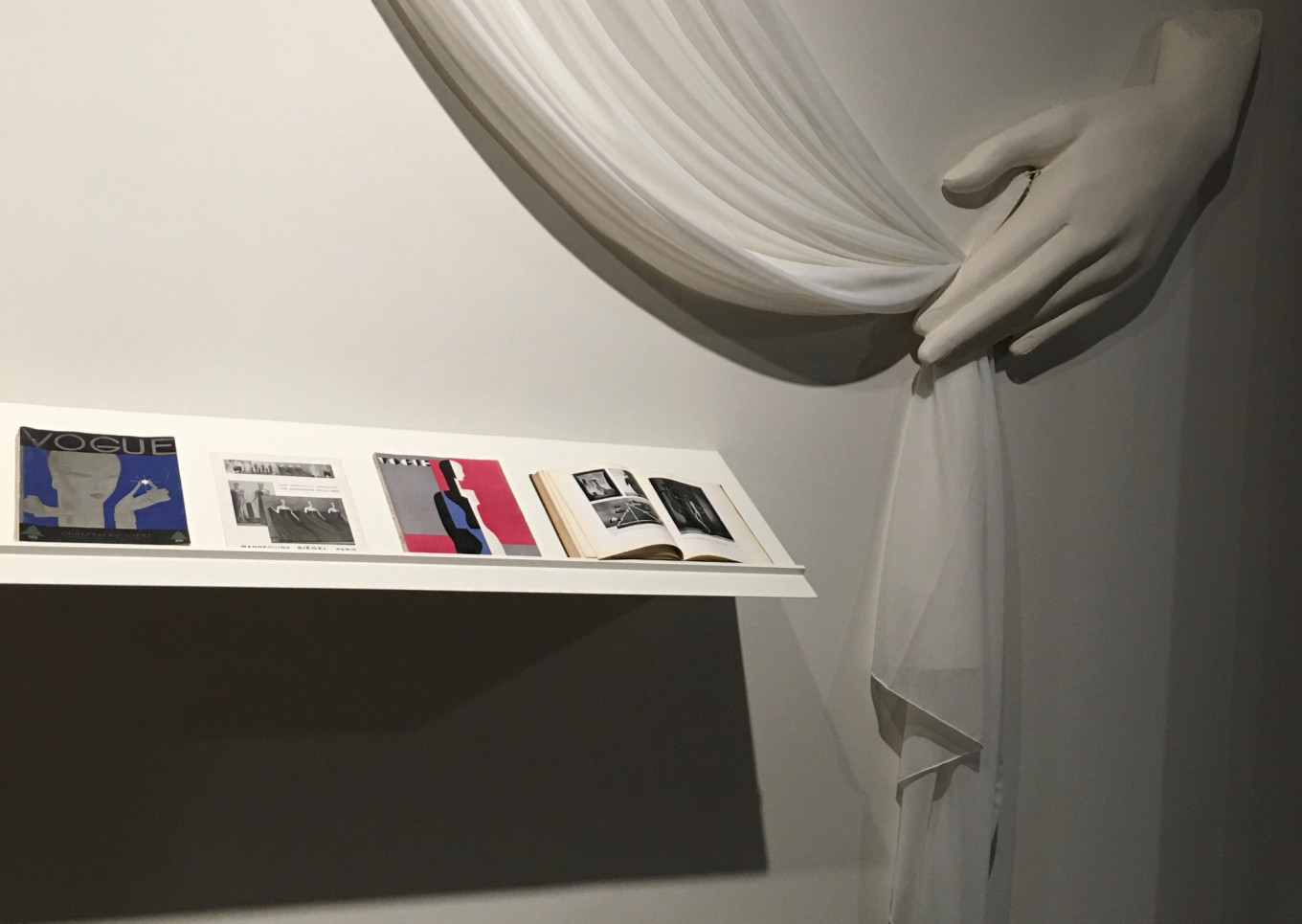

The result is an array of conceptual art which responds, comically and creatively to consumerism. Anna Blessman, in her work Parts Two Plus One creates a bodiless mannequin, hanging a satin drip dress from two silicone casts of her own hands, which emerge, nightmarishly from the gallery wall. Markus Selg, meanwhile, recreates the mannequin as an homage to a 1916 sculpture by German expressionist Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Fallen Man. The original depicts a wounded, crawling figure, a composition which Selg repurposes as a frame for Lipscombe’s athleisure wear. Fractal Abyss is a haunting image of an injured human, frozen Pompei-like on all fours as if escaping a disaster zone, while absurdly clad in the colorful garb of commercial fabrics.

Passerby is now in its third iteration, having been previously shown in London and Paris. For this instalment in Moscow, Lipscombe and McKenzie added extra research into the Russian and Soviet fashion worlds, noting that “Russia had a very interesting relationship with fashion itself, because in a way fashion, and everything that implies about individuality and fantasy is antithetical to Soviet ideas of collectivity.” On display are their findings from the GUM department store archives, the Hermitage collections, ethnographic museums and a condensed history of Russian fashion magazines. Archival issues of Vogue are shown in glass vitrines alongside its Soviet counterparts stretching back to 1929. Alongside this, a specially commissioned documentary about Lydia Orlova, the Soviet Union’s leading fashion editor, is screened.

Passerby is so dense with information that an accompanying brochure and mobile app are produced to help visitors navigate it; “the booklet is important for us” McKenzie notes, because “the audience for this show is so varied.” The artists want to offer visitors multiple ways to engage with the work, “some people just want to come and encounter it as a sort of sensory experience, and then some people who have a bit more specialist knowledge really want the facts and details. We want it to be enjoyable for everyone, we want to cater to different level of experiences and not cut out any of those. We don’t expect the public to read it one way or another.”

As is fitting for a show about consumerism in its various guides, the exhibition doesn’t end in the museum halls but extends to the gift shop, where a pop-up boutique of Atelier E.B. clothing is available for purchase. “There’s no point having vitrines full of our clothes if we can’t offer them to the customer” Lipscombe observes. The relationship between art, fashion and commerce therefore comes full-circle in the exhibition finale, illustrating another example of the changing boundaries which this show highlights. As the artists note, “There’s often a divide between high and mass culture, as if one is important and one is frivolous. We want to turn that on its head.”

Passerby runs until May 10.

Garage Museum. 9 Ulitsa Krymsky Val. Metro Oktyabrskaya, Park Kultury. Garagemca.org