Ordinary Russians are unable to access an increasingly broad range of literature as bookshops and libraries pull titles from their shelves amid a wartime crackdown on political dissent and a November law banning LGBT “propaganda.”

In particular, failing to comply with the controversial — and vague — anti-LGBT law puts shops at risk of large fines or, at worst, closure.

“We are actually afraid,” said Lyubov Belyatskaya, the co-owner of Vse Svobodny, an independent, liberal-leaning bookstore in Russia’s second city St. Petersburg.

The problems faced by bookshops and libraries, which were previously places less affected by Russia’s political repression, are a testament to the mounting pressure on the world of literature that is narrowing access to both fiction and non-fiction titles.

A lack of clarity about the anti-LGBT law signed by President Vladimir Putin late in 2022 — which outlaws public depictions of “non-traditional” relationships — has created confusion among booksellers about which titles can now be legally displayed and sold.

“Everyone started panicking,” said the owner of another liberal-leaning bookstore in St. Petersburg who asked to remain anonymous.

“Some of our vendors stopped supplying some books on their own initiative even though they weren’t really covered by the new law.”

Representatives from several retailers told The Moscow Times that they had received no information from the authorities about which books were prohibited.

As a result, some shops are removing titles on their own initiative or in line with requests from publishers. Others are consulting with lawyers.

Immediately after the law’s signing, “Leto v Pionerskom Galstuke” (“Summer in a Pioneer Tie”), a young adult bestseller about a relationship between two teenage boys, reportedly vanished from shelves at major Russian retail chains such as Chitay-Gorod.

The book was repeatedly cited by lawmakers during the the anti-LGBT law’s passage through parliament.

Some businesses have taken a blanket approach, pulling books with even a passing mention of LGBT relationships or lifestyles.

At Vse Svobodny bookshop in St. Petersburg, managers have been removing books based on lists provided by publishing houses.

“After consulting with their lawyers, [the publishers] decided that these books could be interpreted as some kind of propaganda,” said Vse Svobodny’s co-owner Artyom Faustov.

“The authorities believe that we should determine it ourselves, but how to do this is completely incomprehensible,” he told The Moscow Times.

“A book dealer cannot and is not obliged to read every book and know what’s inside them.”

Other bookshop owners said they will follow official recommendations when they are issued.

“It’s very simple: we have a list coming from the city administration and we comply with it,” a shop administrator at the Bukvoyed bookstore in the center of St. Petersburg told a Moscow Times reporter on a recent visit.

“It will work just like with forbidden literature, such as ‘Mein Kampf’.”

LitRes, Russia’s largest e-book seller, has even asked some authors to rewrite works to comply with the anti-LGBT law, the RBC news website reported in December.

While the anti-LGBT law has had an immediate effect, customers had been noticing changes in Russian bookstores even earlier.

In the fall, Russian bookstores began hiding books authored by so-called “foreign agents,” a Soviet-era designation used by the authorities to label people deemed to be engaging in political activity with support from abroad.

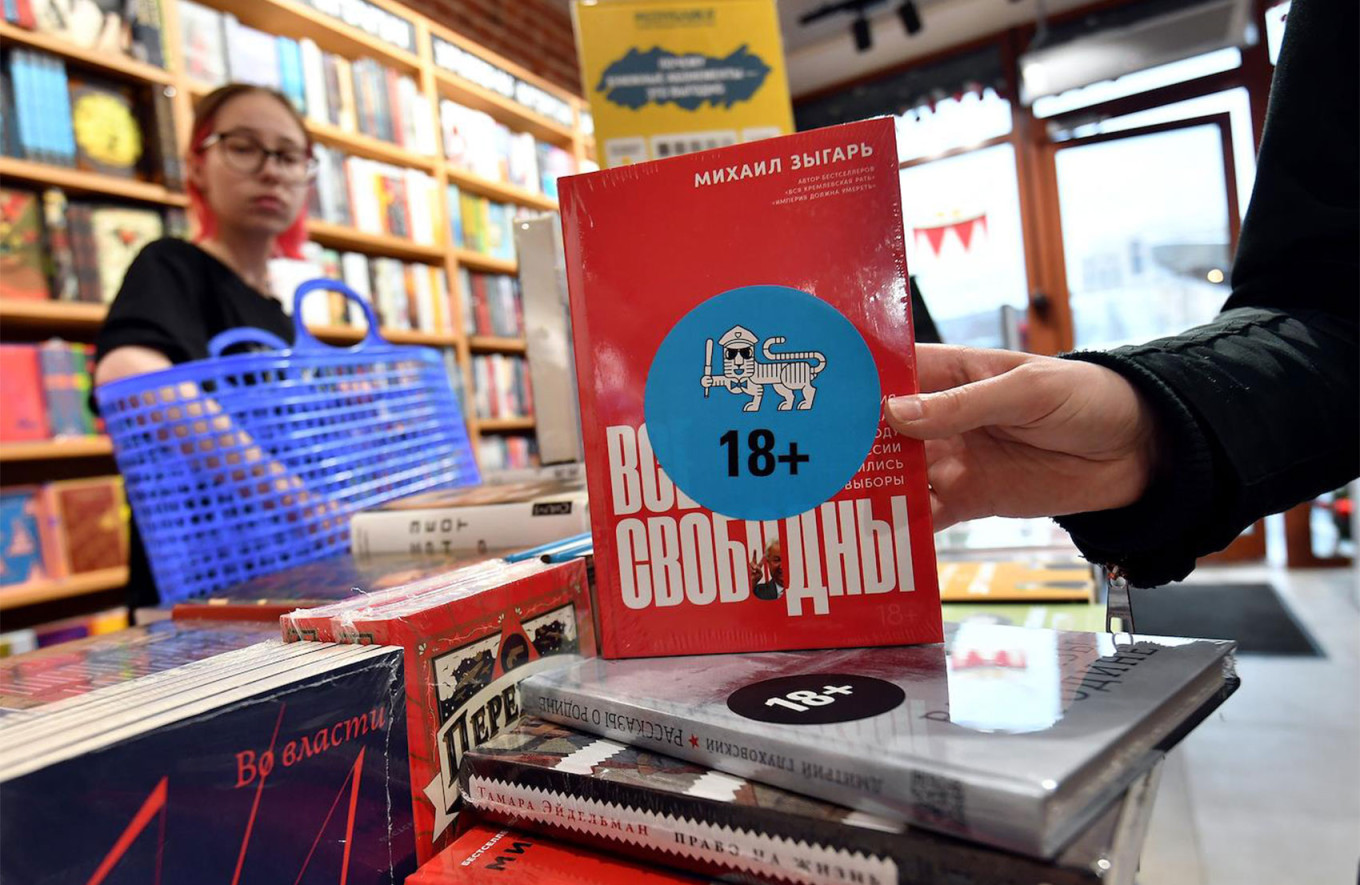

Some bookstores wrapped “foreign agent”-authored books in brown paper or plastic film — sometimes with the designation “18+” on a sticker or scrawled in black marker — and online retailers began displaying the same titles without cover images.

In some cases, readers were reportedly told the books were out of stock altogether.

Bookstore Podpisnye Izdanye in St. Petersburg required a Moscow Times reporter to show ID proving he was over 18 before being prepared to sell him books by “foreign agents.”

Even pro-Kremlin booksellers admit that wartime measures are having an impact on the reading habits of ordinary people.

“We don’t really like censorship… but we must differentiate censorship from, let’s say, justified restrictions, especially in times of war,” said the owner of a nationalist and pro-Kremlin bookstore in St. Petersburg who requested anonymity to give an interview.

“Freedom during a war is a special state of freedom, so to speak.”

The pressure to comply with restrictions comes as bookstores, particularly independent ones, are facing mounting financial difficulties.

“Many of our regular customers left due to mobilization… We’re earning less money, and we have no money to pay fines,” said the anonymous St. Petersburg bookstore owner.

Libraries are also feeling the pinch of Russia’s accelerating literary crackdown.

Independent Russian media last month reported the existence of a list of authors whose books Moscow libraries have been advised to pull from their shelves.

Among the names on the list were Western writers Michael Cunningham, John Boyne, Haruki Murakami and Stephen Fry, as well as Russian poet Oksana Vasyakina.

In addition to Russia’s self-imposed restrictions, some Western writers and publishers have said they will no longer authorize the sale of their books in Russian as a result of the war.

U.S. author Stephen King suspended his contracts with his Russian publisher this spring and Russia’s two largest ebook retailers pulled J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” books in March, saying the copyright owner had revoked their license to sell them.

Unofficial and official bans on certain titles, however, may actually have the reverse effect of the one intended by the authorities, according to Vse Svobodny co-owner Faustov.

“People may not have even thought about buying LGBT-related books or books about foreign agents. And now, due to the fact that they could potentially be banned, they immediately became interested in them and started buying them,” he said.

“As always, all these bans work the other way around.”