As an advocate for the working class, the world’s first female cabinet minister and an unapologetic feminist in revolutionary Russia, Countess Sofia Panina was a trailblazing figure in a time of dramatic social upheaval.

Now, 100 years after her adopted home of the United States gave women the right to vote, the fascinating life story of “Russia’s Jane Addams” has been told in full detail for the first time.

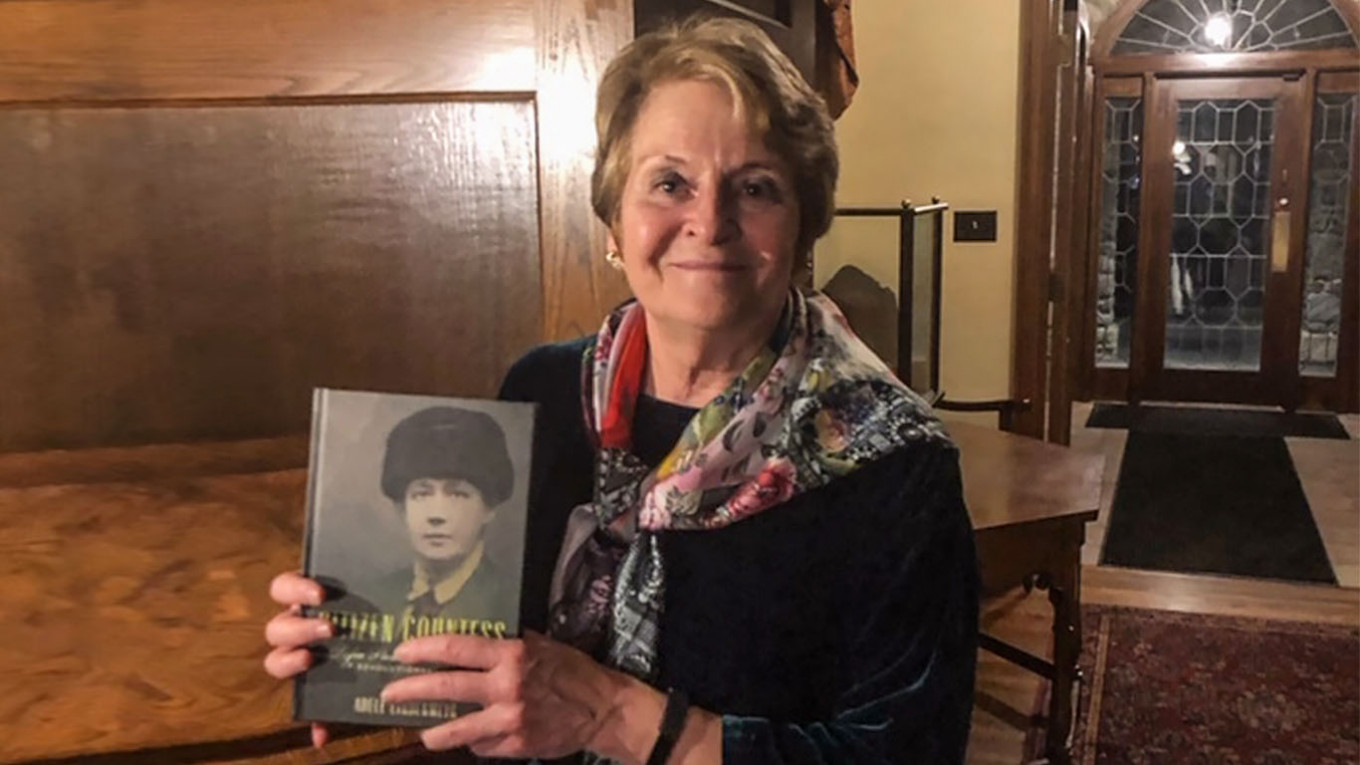

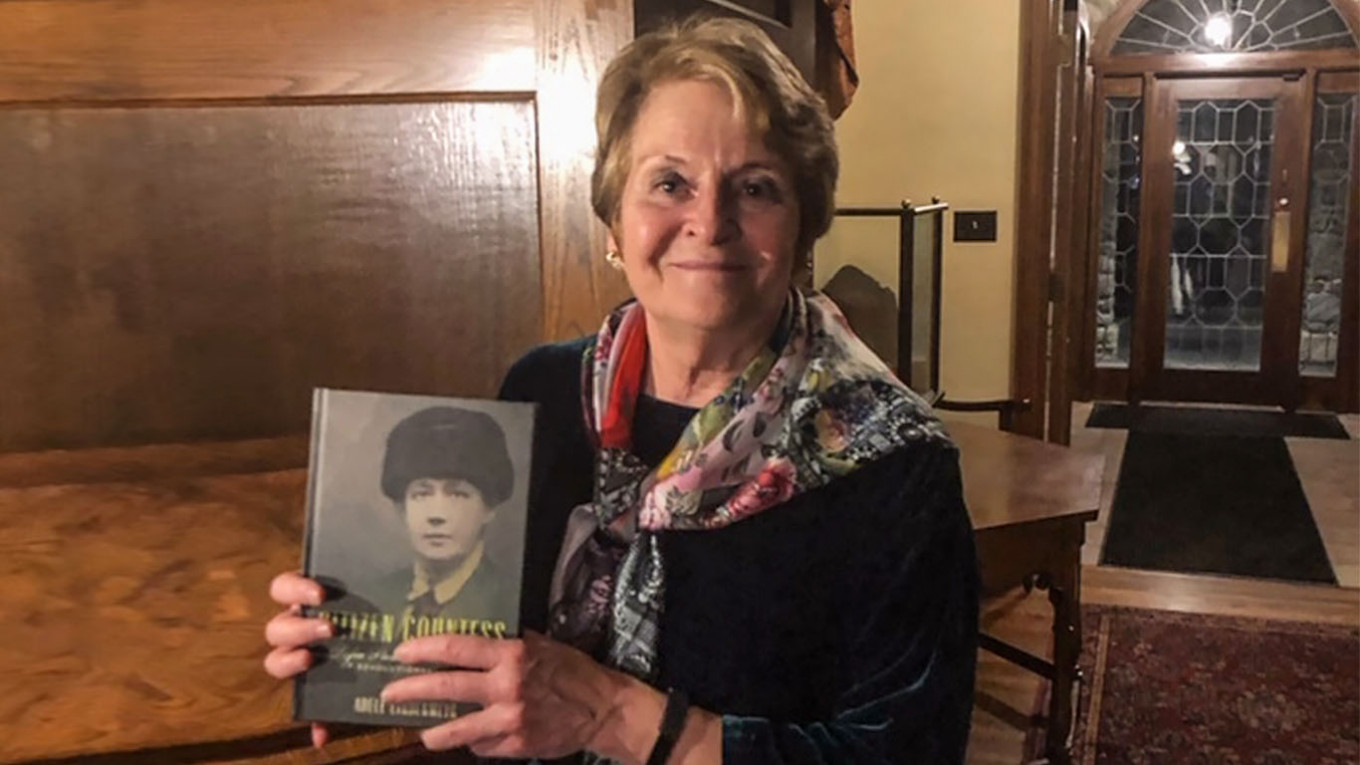

“Citizen Countess” follows Panina’s journey from her upbringing in an aristocratic Russian family to her philanthropy and political office to eventual imprisonment as a “class enemy” and forced emigration abroad.

The book weaves through the many contradictions of her life, painting a nuanced portrait of a woman who was at once an aristocrat and a progressive; the first woman in the world to hold a cabinet position and the first political prisoner to face the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary tribunal.

“Her life documents the successful struggle of so many women in the modern era to emancipate themselves from restrictive class and gender norms,” says Dr. Adele Lindenmeyr, Panina’s biographer and an expert in Russian history.

The Moscow Times spoke with Dr. Lindenmeyr about the citizen countess herself and what women of today can learn from her story.

How did you first discover her?

It was in the course of research that I was doing for my first book, which was a history of Russian charity and public welfare in the pre-Revolutionary period. I was interested in finding out who were the women leaders in philanthropy, if any. I came across her name. I really didn’t know much about her at all. I discovered that she left her papers to Columbia University because she lived the last 16 -17 years of her life in the United States.

And then you did research on her all over the world for 20 years?

Yes, I did. We were still finding things up to a few years ago, including, for example, in a Moscow archive — an amazing collection of letters that she wrote to a girlhood friend. She was a private person. As far as I know, she didn’t keep a diary. The sources on her life before she left Russia have big gaps in them. She destroyed documents before she gave them to the Columbia archive. In fact, I found a letter she wrote to a cousin as she was going through her papers: “I will burn everything personal and dear to me.” I had the challenge of filling in the gaps, making the inferences that were reasonably valid but also speculative and trying to get to know her as an individual.

She seems like an incredibly forward-thinking woman. Why do you think that was?

There were historical structural reasons for her independence and seeming modern. First of all, Russia, especially of her class, she was not unusual. They were very independent. Especially those who were independently wealthy — and she was extremely wealthy. She had complete control of her money when she turned 21, even though she was married at that time. Then when her grandmother died, she inherited the rest of the estate… So for one thing, it’s easier to be independent when you’re very wealthy.

Then she had the example of her mother, who was very influential, I think. Then she came of age during the Russian feminist movement and the movement for equal rights for women and, although, she never was an outspoken member of the Russian feminist movement she was, certainly, instrumental in gaining political rights for women, for example, in 1917. She was one of the founders in 1900 of the Russian society for the defense of women or the protection of women, which was the largest anti-prostitution society. She wasn’t afraid of taking on controversial social causes.

If she were alive today, what do you think she would be doing?

Nobody has ever asked me that before. What would she be doing? If she were in Russia, what would she be doing? She would probably be running some nonprofit. You know, as apolitical as possible, a nonprofit. That’s where her heart lay. It would be probably connected to culture, education, popular enlightenment.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

‘Citizen Countess’ Chapter 7: Revolution in Petrograd

Countess Sofia Panina relinquished her self-identity as a non-partisan social worker and entered the political arena when the monarchy and tsarist government fell at the end of February 1917. As in the lives of countless others, the war proved to be impetus behind this decisive turning point in her life. War-related relief work drew her increasingly closer to the liberal opposition as she collaborated with its leaders and affiliated organizations. In the wake of the February Revolution, they elevated Sofia to unprecedented political prominence. In rapid order she accepted both elected and appointed positions in three major political bodies that were playing decisive roles in the unfolding revolution: the Petrograd City Council, the Central Committee of the Kadet Party, and the cabinet of the Provisional Government, where as an assistant minister she became its only female member and the first woman in history to hold a ministerial position.

Her experience in 1917 stands out as a striking exception in the annals of the Russian Revolution. Russia led Europe in the introduction of universal female suffrage in 1917, the culmination of a decades-long feminist movement. But the leadership of parties across the political spectrum was overwhelming male, and when the newly enfranchised women and men of Russia voted in mid-November for delegates to a new national Constituent Assembly, there were few women on the party lists of candidates.

By agreeing to take these high-level governmental and party positions, Sofia transformed herself from a philanthropist into a political actor on the national stage and entered the vortex of Russia’s crisis in 1917. At Kadet party conferences and meetings of the Provisional Government’s cabinet she observed at close range liberal politicians’ struggle to control the accelerating pace of the revolution. In the volatile political atmosphere of the Petrograd City Council she heard Bolsheviks advocate a course that she believed would bring her country into a state of anarchy and ruin. In the streets the workers she thought she knew from her years of philanthropic work rejected the leadership of well-intentioned moderates like herself, and voiced anti-war, pro-socialist slogans inflected by class hatred. Sofia’s involvement in the revolution tested her endurance, courage, and most cherished beliefs – the possibility of harmony between classes, the natural leadership of the educated and cultured, and Russia’s destiny as a peaceful, enlightened, European nation.

The year 1917 began in Petrograd in an atmosphere of impending crisis, intensified by widespread rumors about government paralysis, treason, and conspiracies. Economic disaster, signaled by a spike in prices and extreme shortages of food and fuel, loomed over the city. The especially cold winter compounded the misery. Eyewitnesses and historians agree that the first Russian Revolution of 1917 began on February 23, the socialist holiday of International Women’s Day (March 8, according to the western calendar), when between 90,000 and 100,000 men and women workers went on strike that day, making it the most serious episode of labor unrest since July of 1914. The number of strikers doubled the next day, fed by men from metalworking factories and armaments plants and women from the city’s textile mills. Students, tram and horse-cab drivers, artisans and servants, professionals and office workers joined the strikers in the days that followed. Demonstrators defied orders to disperse. Mounted police, Cossack regiments, and soldiers from Petrograd’s garrisons began to waver when commanded to put down the unrest.

As civil and military authority in the capital disintegrated and protests reached a crescendo, Sofia took her first steps onto the political stage. Soldiers from the city’s garrisons, having ignored previous orders to quell the demonstrations, openly joined the revolt on February 27. The soldiers, one unsympathetic upper-class eyewitness recounted, “were disheveled, in unbuttoned greatcoats with their hats on the backs of their heads[;] they ran back and forth from one corner to the other and did not look military at all.” He remembers seeing Sofia, whose home on Sergievskaya Street was just a few steps from Liteiny Prospect, moving between her house and the “mob” of soldiers and workers who swarmed along the broad avenue. She ignored the tearful pleas of her elderly servant not to go out onto the street, assuring him that the crowd would not harm her. Communicating by telephone, she kept the city council informed of the situation around her house and the mood of the soldiers.

A short distance away stunned members of Russia’s parliament, the Duma, milled inside the Tauride Palace, uncertain about what to do next. After observing the soldiers wandering aimlessly along nearby Liteiny Prospect for some time, Sofia rushed into the palace and began to berate the politicians. “They are waiting for orders,” Sofia reproached them. “They are expecting the members of the Duma. Go to them. Take them in your hands. Look,” she continued, “this is a flock that has gone astray.” The revolt reached its climax on March 2, when Nicholas II was persuaded to abdicate on behalf of himself and his hemophiliac son in favor of his brother Michael. Michael refused the throne, however, ending the Romanovs’ three-hundred-year rule. Virtually overnight Russia became the world’s largest republic.

Contemporaries hailed the February Revolution as bloodless (which it certainly was, compared to later events in the capital), but it nevertheless claimed as many as two thousand victims. Its violent undercurrent immediately struck Sofia very close to home. On the evening of March 2 her cousin Dmitry Viazemsky was riding in the front seat of an automobile carrying the Provisional Government’s new Minister of War. Suddenly a volley of shots exploded from behind the car, and a bullet struck Dmitry. He died the next day, the first of many sacrifices Sofia and her family would make to the revolution.

Sofia’s first official role resulted from an internal revolt within the Petrograd City Council in early March, when progressive deputies deposed the conservative mayor and elected a moderate liberal in his place. The council invited several women who had been longtime leaders in charity, education, and public health in the capital to join the council. Sofia and the other first female deputies on the Petrograd City Council were harbingers of the political equality that supporters of women’s rights had been seeking for two decades. Russia’s leading feminists were well aware of the tepid support for political equality within the Kadet party that controlled the Provisional Government, and the considerable resistance their cause still faced in 1917. To force the issue, the League for Women’s Equal Rights organized a massive and unprecedented demonstration. On March 19, a surprisingly mild late winter day, an estimated forty thousand women accompanied by brass bands playing revolutionary anthems marched down Nevsky Prospect to the Tauride Palace. Led by an open automobile carrying both feminist leaders and the former terrorist Vera Figner, the marchers waved banners demanding rights for women. Initially the country’s new political leaders in the liberal Provisional Government and the socialist Soviet advised the women that their demands were “premature” at this time of revolution. But they finally conceded to the crowd outside the palace that any law introducing universal suffrage would include women’s right to vote. Doubting the dependability of such promises, leaders of the women’s rights movement sought an audience with the new Prime Minister, Prince G. E. Lvov. Two days after the march Sofia joined Figner and feminists from the center and the left to meet with Lvov, who assured them of the new government’s commitment to women’s suffrage. Shortly thereafter the Provisional Government introduced a series of laws establishing equal rights, culminating in a law of July 20, 1917, that made Russia the first European nation to grant full voting rights to women in national elections.

After entering the Petrograd City Council and the movement for women’s rights in March of 1917, Sofia finally declared her political affiliation by joining the Kadet Party. The reason she gives in the memoir she wrote thirty years later is straightforward. “Many of those around me considered me a socialist” because of her years of work with the city’s laboring poor, the one-time “Red Countess” explained. Therefore “I considered it necessary, at the moment when the political struggle intensified, to establish my position with complete precision and dissociate myself from the socialist madness that had seized the country.” She chose the Kadets because it was the only party that “openly battled with advancing bolshevism.” Sofia considered this a life-altering decision; “my entire future fate,” she claimed, “was determined by this moment.” Almost as soon as she officially joined the Kadets, Sofia vaulted into the party leadership. Meeting on April 10, 1917, the party’s central committee decided to increase its size by coopting new members, and elected Sofia by secret ballot as one of them. Her membership on the central committee was reaffirmed on May 12, when an expanded committee of sixty-six members was elected. Sofia and Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams were the only women.

At a meeting on May 24, 1917, two weeks after her formal election to the Kadet central committee, the Provisional Government cabinet appointed Sofia to be assistant minister in the newly created Ministry of State Welfare. Sofia carried out a variety of functions during her stint as assistant minister of welfare but stayed outside of both the public spotlight and the inner circle of her party and government. Her principle responsibility involved determining the fate of the hundreds of schools, orphanages, and other charitable institutions that had been supported wholly or in part by the tsarist government and members of the now deposed imperial family. Among the institutions slated for reform were the institutes for noble girls, including her alma mater the Catherine Institute and its old rival Smolnyi Institute. Her mission led her to make two visits to Smolnyi, where its elderly retired headmistress, Princess Golitsyna, still lived with a few stranded pupils. When Sofia arrived the women were fearful, “seeing in me a representative of the terrible and hated revolution,” although their attitude softened when they learned that their official visitor was a countess and former institutka herself. The February Revolution had left its mark on Smolnyi’s walls, Sofia discovered. Dramatic evidence of the revolution’s impact was revealed in one of the large and empty classrooms, where four huge portraits of the two last emperors and empresses had been torn off the wall and thrown face down on the floor. Visiting one of the dormitories, Sofia could not help but notice a photograph of Minister of War Kerensky pinned over one girl’s bed, evidence of the heroic status he enjoyed in the early summer of 1917, when the advance on the Austrian front he was leading still promised success. Scattered groups of frightened girls huddled in the huge classrooms, “representatives of this once proud and pampered Institute… [and] of something gone and doomed, living fragments of history, so young and helpless before the approaching hurricane that was fated soon to scatter them across the entire face of the Russian land.”

Written in emigration and tinged with nostalgia for a lost world, Sofia’s account captures how the revolutionary future and the discarded past were still closely intertwined during 1917. Representing herself as an intermediary, she travels in the liminal space between the imperial past, where the old headmistress weeps silently amidst discarded portraits of deposed rulers, and a future full of hope, where girls naively transform radical lawyers like Kerensky into revolutionary heroes. With the benefit of hindsight, she knew that not only Smolnyi Institute but also the lives of its young pupils were “doomed.” Sofia’s ministry fought to hold onto the spacious building, hoping to turn it into a model institution for pre-school education, but the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies wanted it for its headquarters. Sofia had to return to Smolnyi to inform Princess Golitsyna that her beautiful building now belonged to representatives of Petrograd’s workers and soldiers. This sad errand accomplished, she also resigned from her ministerial position.

From “Citizen Countess: Sofia Panina and the Fate of Revolutionary Russia” by Adele Lindenmeyr. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

For more information about the book, author and Sofia Panina, see the publisher’s site and a site dedicated to book.

There is also a Russian language site dedicated to her life and work here.