In Russia today there is a belief that the food served in Russian Orthodox monasteries is the apotheosis of Russian cooking. Some people insist that the monasteries preserved the very best that had survived from ancient Russian cuisine — beautifully prepared, delicious, healthy food.

But isn’t there a contradiction here?

On the one hand, Christianity in general and Orthodoxy in particular preach modesty and the renunciation of worldly pleasures, including gluttony. And on the other hand, we see quite appetizing and sometime even rather rich dishes in monastery cuisine. So which is it?

In fact, supposedly “heavenly” Orthodox cuisine is nothing but a myth. Throughout history, monasteries were filled with people who came from all walks of life. We do not mean only the poor, but people from truly all walks of life — peasants, bourgeoisie, nobles. That is, people who been raised on Russian food. They brought it to the monastery.

It is unlikely that there were many good cooks among them for the simplest reason. According to the statistics of the 1890s, there were a total of 684 monasteries in Russia (484 male and 200 female), 6,813 monks and 5,769 nuns. That is, roughly speaking, an average of 18 people per monastery. How would you find an especially good chef among them? Whichever monk knew how to make porridge was sent to the kitchens.

Of course, there were also “ceremonial” monasteries often visited by tsars and tsarinas. And some unlucky royal wives, such as Ivan the Terrible’s wife Anna or Peter the Great’s wife Yevdokia, unwittingly found themselves as nuns, exiled to convents by their spouses. Those convents had excellent kitchens. An excerpt from the description of a meal at Suzdal’s Pokrovsky Monastery in the 17th century includes meals of “sterlet on a spit, pike perch soup, sterlet pies, white sturgeon…” In part, this was because the tsar and his retinue had to be properly received and fed when they visited. In part, the noble nuns were also in no hurry to abandon their culinary habits.

In all other monasteries, the nuns and monks cooked for themselves. Today sometimes professional cooks are invited to work in popular monasteries to serve pilgrims and the huge number of people who visit the monastery.

But let’s not get carried away. Even in those popular monasteries everyday food is just everyday food. It’s a delusion to think these are places that produce culinary masterpieces. All the food is simple and inexpensive: vegetables, bread, milk and fish. The only food “on the outside” you won’t find there are pelmeni (dumplings) or hotdogs — but that’s only because they are made with — or at least supposedly made with — meat.

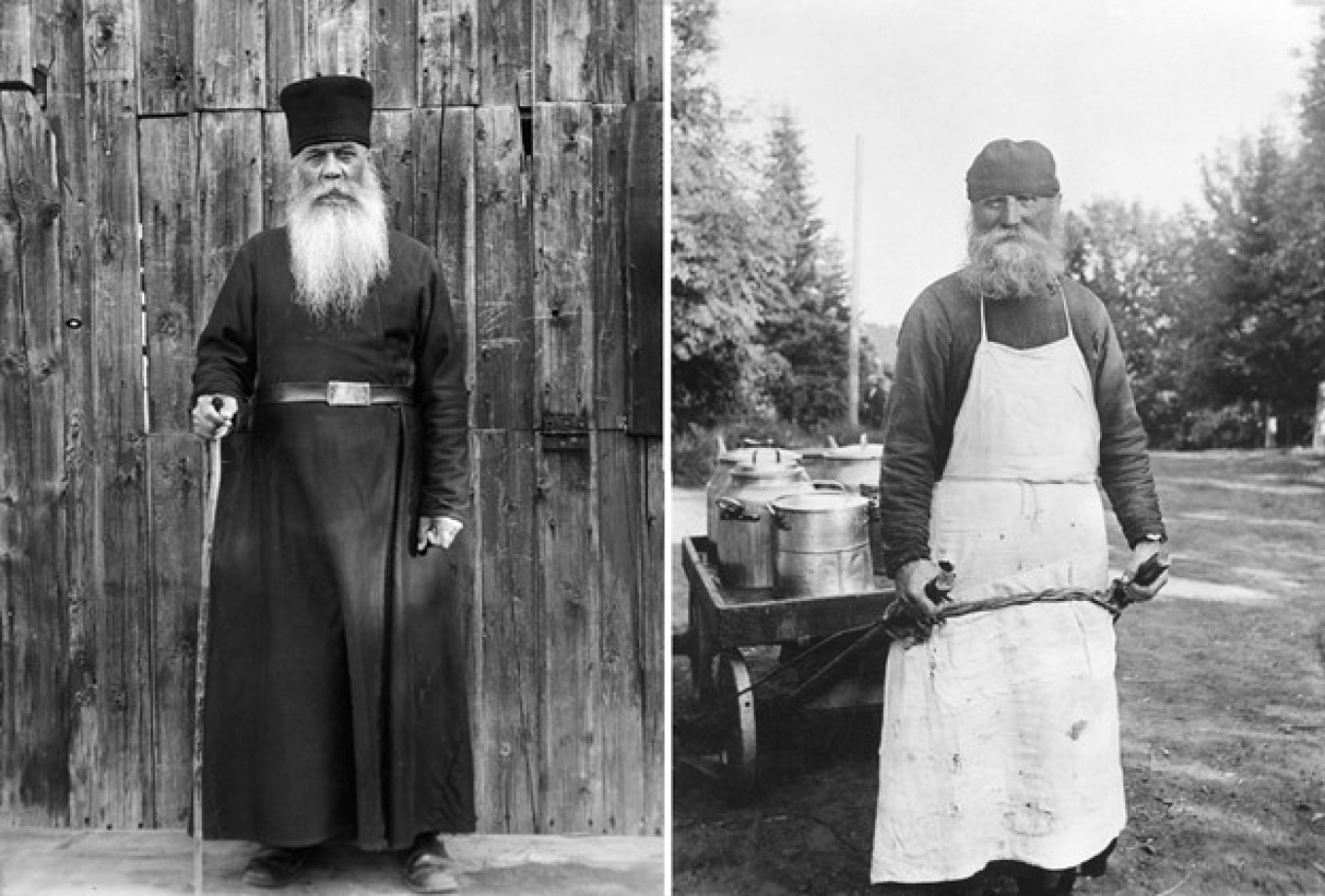

Historically, the monks always cooked for themselves. And they cooked the dishes they knew and loved. These were the same dishes that they were used to before they became monks. Monastic cuisine in this sense is not elegant — it’s simple, folk cuisine. The only exceptions are when hierarchs (bishops) come for a solemn feast day service. Then they prepare a richer meal.

So how can we explain today’s stereotype that monastery cuisine is the best example of Russian cuisine? There are two factors at play.

On the one hand, Russians cherish the feeling that in the past food used to be tastier, the water cleaner, and the trees taller. This is nothing new. Two hundred years ago author Mikhail Lermontov wrote, “If only people were like those men of lore, so different from today’s brood.” This yearning for the blessed past appears in Russians at the first mention of monastery cuisine. The monasteries happily exploit this, although sometimes their attempts fail. For example, they serve tomatoes at the so-called “historical monastic table.” Tomatoes were, in fact, almost completely unknown to our ancestors even in the middle of the 19th century.

There is, however, another reason. Since the Soviet period, there is almost no traditional monastery cooking left. But in pre-revolutionary reality, monasteries were indeed one of the centers that preserved traditions and habits, including culinary traditions. And even at the beginning of the 20th century you could still easily find ancient dishes at monasteries: a cold soup called botvinya made of kvass and fish, kulebyaka (a pie with several fillings), dumplings, cabbage pies, and so on. That is, monastery cuisine has always been somewhat more conservative than everyday secular cuisine. Today, for many people, it is something of a “food museum.”

But do our contemporaries find it more appetizing? Well, to each his own. What people find delicious and healthy food are different in each century.

We like to prepare some dishes from that ancient menu. We aren’t, however, terribly concerned if they follow the strict, mostly vegetarian monastery rules. The main thing is that they taste good — like this pie filled with cabbage and eggs. By the way, it is not made with a traditional yeast dough. It is a different interpretation of our ancestor’s recipe for the modern kitchen.

Monastery Cabbage Pie

Ingredients

For the dough

- 200 g (7 oz or 7/8 c) butter, very cold

- 200 g (7 oz or 1 c) 10% fat sour cream

- 300 g (10.5 oz or 2 ¼ c) highest grade wheat flour

For the filling

- 400-500 g (14 oz to 1.1 lb) cabbage

- 100 ml (7 Tbsp or 2/5 c) milk

- 50 g (1.7 oz or 3.5 Tbsp) butter

- 3 eggs

- 1 tsp sugar

- salt to taste

- 1 tsp starch

- egg and milk for basting, if desired

Instructions

- Pour the flour into a large bowl. Coarsely grate the very cold butter, occasionally dusting the grater with flour to make the butter easier to grate.

- Rub the butter into the flour with your fingers until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

- Add the sour cream and start kneading the dough, first with a spoon. When the ingredients are combined, continue kneading with your hands until the dough comes together into a lump. Do not knead until smooth!

- Shape the dough into a thick pancake, wrap in clingfilm and put in the refrigerator for 30-40 minutes.

- Put the eggs in a saucepan, cover with cold water, and put on heat. When it comes to a boil, boil for 8 minutes, then turn off the heat but leave the egss in the hot water for another 8 minutes. Then rinse the eggs under cold water, cool and peel.

- Shred the cabbage finely. Crush the cabbage with your hands and transfer to a large skillet.

- Add milk and sugar to the cabbage, put on the burner, bring to a boil and stew until the cabbage is soft. When ready, salt the cabbage to taste and add butter. Raise the heat and boil the mixture, stirring constantly, until all the milk has evaporated.

- Allow the cabbage to cool. Transfer it to a clean dish so that it cools more quickly.

- Finely chop the hard-boiled eggs and add them to the cabbage. Taste the filling; it should be well salted.

- Preheat the oven to 190°C /375°F.

- Divide the dough into two parts. Roll one out to a thickness of about 5 mm (1/4 inch). Fit the dough on the bottom and sides of a 26 cm/10 inch round pan and sprinkle it with starch (this is necessary so that the moisture from the filling does not make the dough wet).

- Spread the cabbage filling over the pastry.

- Roll out the second part of the dough into a pie-sized circle and cover the cabbage filling with it. Pinch the edges of the dough.

- If you wish, the pie can be basted with egg mixed with milk.

- Put the pie in the preheated oven for 35 minutes.

… we have a small favor to ask.

As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

It’s quick to set up, and you can be confident that you’re making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.