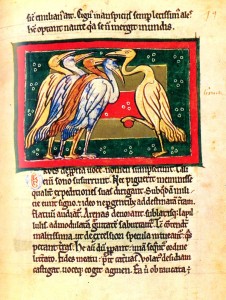

Crane /grus/ 10.2×6.9 cm

The text originates from Isidor /XII.VII.14/ who quotes Lucan /Pharsalia,7.716/ and draws on writings by Pliny /23.80; X.29.42/ and Solinus /10.12— 16/, his story is also traceable to Aristotle /IX.614.B. 18/. In the text the chief emphasis is on the cranes’ strict orderliness in life; they fly in a strict line and in the night one of them is on the watch, guarding the sleeping flock. The sentry stands on one leg not to fall asleep. They swallow sand and small stones to ballast themselves during the flight. You can tell a crane’s age by its colour, for in old age it becomes all black. Pointing to their strict formation during the flight, “Aviarium” /39/ emphasizes the importance of orderliness in the life of man, which ought to facilitate man’s ascend to piety. The “Bestiary of Love in Verse’: /1473/ presents the crane in the spirit of secular love lyrics. Pierre of Beauvais /11.142/, Albert the Great /XXIII.1.49/ and Brunetto Latini /I.V.165/ considerably expand that part of the story in which the line of flying cranes is compared to a military formation of “knights marching to fight”. In the reliefs of Romansque and Gothic churches the cranes are part of the compositions encting the fable about the wolf and the crane /for instance, the reliefs of the Cathedral in Autun/.