“DAU” / Kinopoisk.ru

At the end of January, parts of what is surely Russia’s most spectacular film project premiered in Paris. The project — something between a film series and an extended social and psychological experiment — is called “DAU” and directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky, a filmmaker with only one major work before this project.

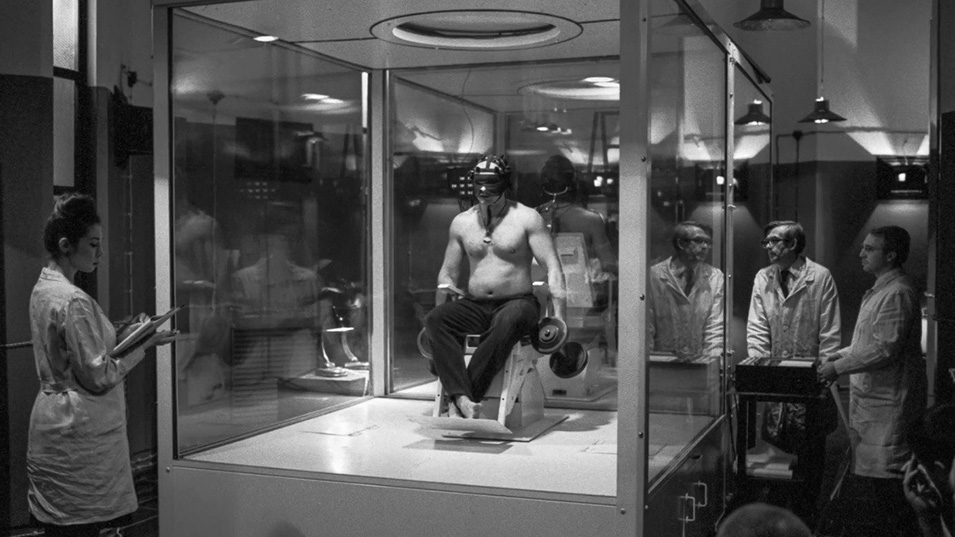

It is based, in part, on the life of the Soviet scientist Lev Landau, here played by the classical music conductor Teodor Currentzis. Most of the cast of almost 500 principal characters and 10,000 extras are played by non-actors. The film project initially had a script by novelist Vladimir Sorokin and follows the life of the people working in a Soviet research institute from 1938 to 1968.

Funding was provided by a pantheon of European production companies, television channels, and foundations, including Eurimages; the Swedish Film Institute Film and two other Swedish production groups; Arte France Cinema and other French companies; three German foundations and production companies; and several groups in Netherlands from other countries.

Funding was also provided by Sergei Adonyov, a wealthy businessman who supports a variety of liberal media and non-traditional contemporary cultural institutions in Russia.

Most of the filming took place in an enormous set built in Ukraine that recreated, to some extent, a Soviet-era research institute. Cast members lived on the set; dressed in the clothes of the eras being filmed, had period haircuts, glasses, and medicines; bought food and goods that were typical of the time periods, using real rubles from past decades.

“DAU” / Kinopoisk.ru

More than 700 hours of film was shot from 2008 until 2011, although most of the “life” in the institute seems not to have been filmed. Of the material that was filmed, it’s apparently not clear what was scripted and what was real or played to look real. Some participants have expressed discomfort or distress about the morality of some of the filming.

But all of the information about the film is coming to Russia second-hand, since less than a dozen film critics have seen any part of the film on the big screen. Some saw parts in London; others have been watching it in Paris, where 13 parts are being shown as part of an installation that includes faux ruins, a light sculpture and a theater set.

The material will be transformed into films, television series, documentaries and media-art installations.

“DAU” / Kinopoisk.ru

The great irony of the project is that a Russian film that may revolutionize film-making today as much as Sergei Eisenstein’s films did in the 1920s may never be shown in Russia.

The issue is perhaps not the grim depiction of the Soviet Union — because the film is both a recreation and a fantasy; a celluloid version of the past, the invented past, and the present — but due to some of the story lines, like a graphically depicted gay love story, that are not permitted on the screen in Russia today.

Read More

Podcast: The Kremlin Wants North Korean Workers Out. And Behind the Scenes of DAU, a Russian Film Spectacle