This summer the Anatoly Zverev Museum is celebrating the work of four geniuses — one literary and three artistic. In the exhibition entitled, “The Flying Troika and Its Passengers,” Nikolai Gogol’s novel “Dead Souls” is interpreted by Marc Chagall, Anatoly Zverev and Vadim Kosmatschof.

The non-conformist artist Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986) loved Nikolai Gogol, and over the years the museum that bears his name has exhibited his portraits of Gogol and illustrations of the writer’s works. The idea for this exhibition was born when curator Polina Lobachevskaya saw Marc Chagall’s lithographs illustrating “Dead Souls.” And as she told The Moscow Times, “Zverev was obsessed with Gogol’s ‘Dead Souls’ for virtually his whole life. He loved Gogol, and ‘Dead Souls’ in particular, and there are many illustrations of his in various collections. When we saw Chagall’s astonishing lithographs, I immediately had the idea of doing an exhibition to highlight the parallels between these two great artists.”

These lithographs are not widely known. Marc Chagall (1887-1985) studied lithography in Berlin in 1922. While he was still learning this craft, he was approached by the French art dealer Ambroise Vollard to make a series of lithographs illustrating the work of Russian literature of his choice. Chagall proposed “Dead Souls” and spent two years, from 1923 to 1925, producing 96 lithographs. For some reason, Vollard did not immediately begin work on the publication, and then died unexpectedly in a car accident in 1939. Chagall gave a set to the Tretyakov Gallery, but they remained unpublished in France for almost another decade.

After the war another publisher, Teriade (the pen name of Efstratios Eleftheriades) commissioned a French translation of “Dead Souls,” asked Chagall to make 11 more lithographs and published the book to great acclaim. It won the Grand Prix at the Venice Biennale in 1948.

And then, decades later in Moscow, the collector Boris Fridman acquired a set of the works and shared them with AZ Museum.

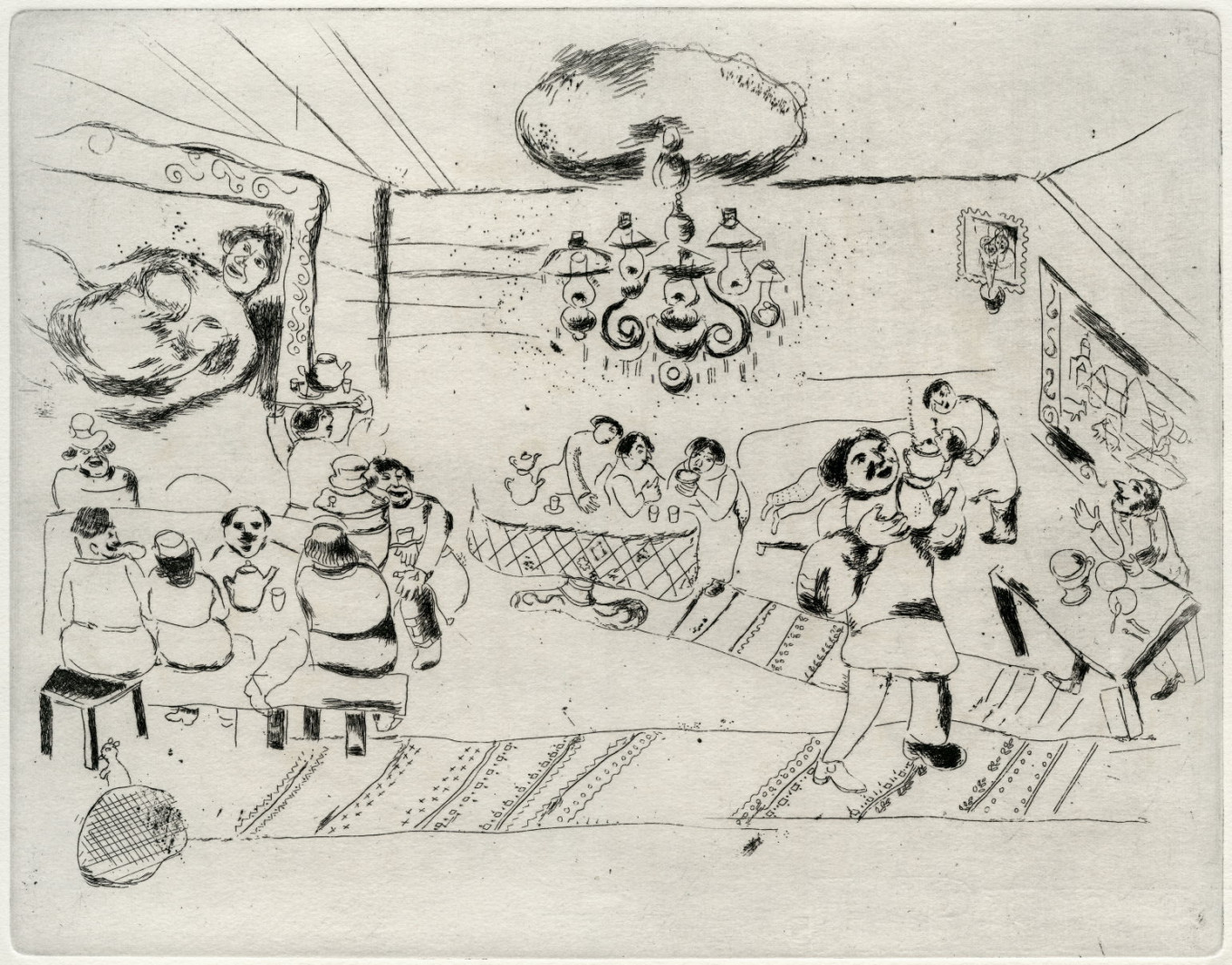

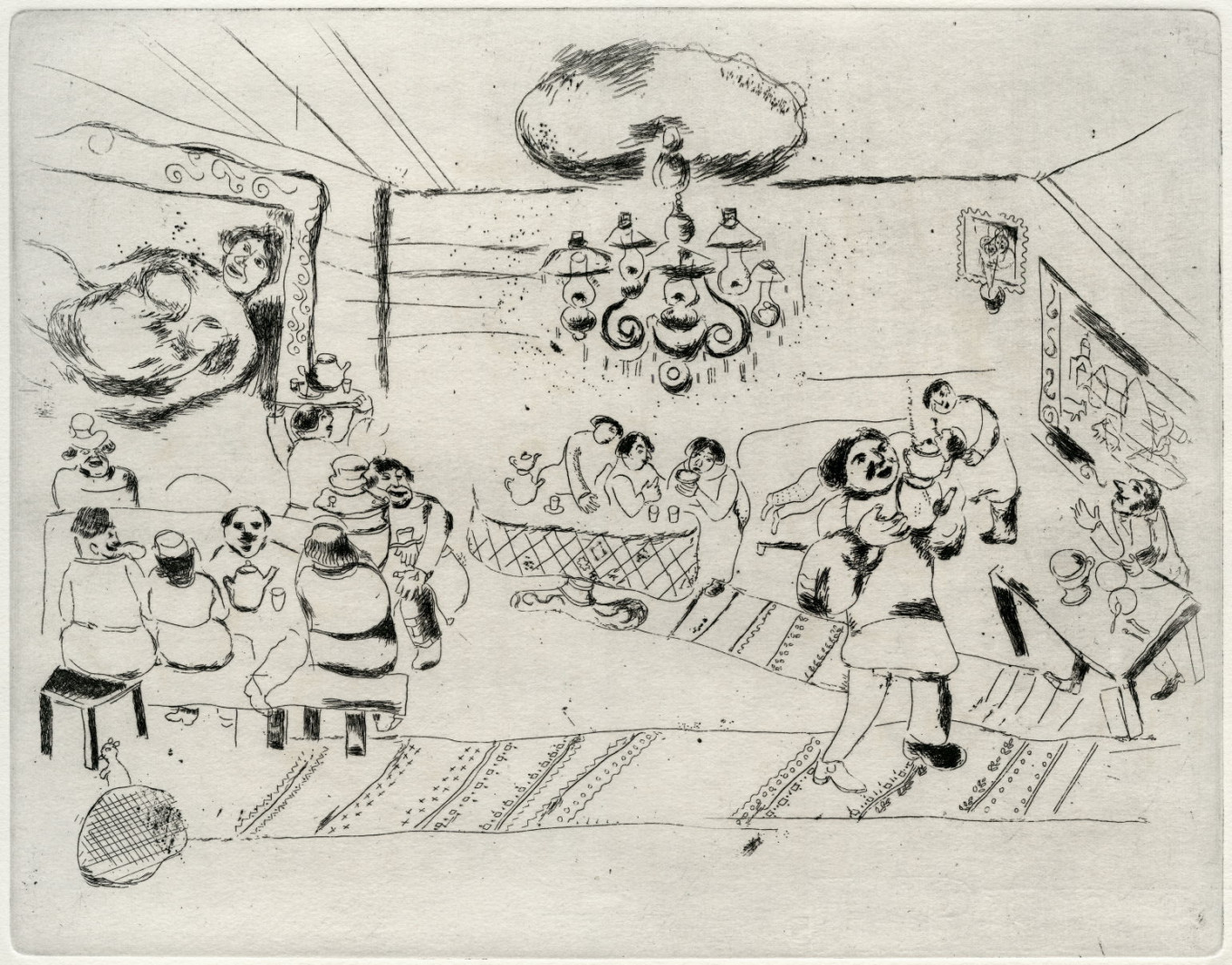

“Inn,” Marc Chagall, 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. Fridman

“Inn,” Marc Chagall, 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. FridmanThe troika

“Chichikov’s Troika,” A. Zverev, 1983 Tretyakov Gallery

“Chichikov’s Troika,” A. Zverev, 1983 Tretyakov GalleryAlthough Zverev’s drawings and paintings and Chagall’s illustrations would have made a fine exhibition, Lobachevskaya thought a show of works about “Dead Souls” needed a third artist — a troika, both literal and figurative.

The image of the troika is the most famous image in Gogol’s novel — and indeed one of the most famous in Russian literature. At the end of Part One, Pavel Chichikov, the main character, is leaving town. He has been buying up the “souls” of serfs who have died between censuses, which owners are eager to sell since they have to pay taxes on them until they are officially stricken from the books. Chichikov’s carriage is being pulled by a troika of horses that fly across the landscape as if they had wings. Gogol tells us that “Chichikov just smiled as he lightly bounced on his leather cushion, since he loved to drive fast. And what Russian doesn’t love to drive fast?”

As the carriage flies along the road, kicking up dust, the narrator asks if Ancient Russia — “Rus” — is like that troika, “rushing ahead, a high-spirited troika that no one can overtake… Rus, where are you racing to? Answer! She does not answer. The bells start up their fantastical jingling; with a thunder clap, the air is torn into tatters and turns into the wind; everything — everything on earth — flies by, as other nations and states step aside, looking on scornfully, to make way for her.”

This image gave the exhibition its name “The Flying Troika and Its Passengers” and its third artist, the sculptor Vadim Kosmatschof. Lobachevskaya said, “After we had a dialog of two artists, we wanted to create a sculptural image of the “flying troika.” We discussed many options, and we came to the conclusion that the most interesting artist for this would be Vadim Kosmatschof.”

Kosmatschof, a Russian-born, award-winning artist who has lived in Europe for many decades, leapt at the offer to provide an image for an exhibit, since Gogol is one of his favorite writers. “My main way of perceiving the world is through sculptural images. I keep my eyes wide open and catch sight of a broad range of phenomena, everything from banal nonsense to the expanses of space. However odd it might seem, the two often go hand in hand. The trick is not to stoop down to illustrative thinking… in the literary subtext I saw, above all, a metaphor with a series of sculptural associations. One of them took three-dimensional form.”

The association that took form is powerful metal troika, both heavy and airy, that explodes from the wall of the first floor.

To complete the exhibition, two more artists were invited to contribute: Mikhail Shepilov and Alexandra Anokhina, who brought the lithographs to life in animations.

The ride

“Chagall Drawing ‘Dead Souls’,” 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. Fridman

“Chagall Drawing ‘Dead Souls’,” 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. FridmanThe exhibition begins on the first floor, where visitors begin their journey, as it were, on the roads of old and new “Rus.” Kosmatschof’s troika bursts into the room and seems about to launch itself into the animated film of Chagall’s lithographs that morph into Russian trains and then Moscow traffic. If there is one constant in Russia, it is that Russians still love to drive fast.

On one wall are Chagall’s enchanting images of the road into the town of “N” (a convention used to designate any small town where action in a novel takes place). On the opposite wall two Chagall lithographs and two Zverev drawings capture Gogol and his world in brush and pen strokes that are as contradictory as the writer’s world: delicate and bold, dark and airy, whimsical, comical and dark.

Visitors can continue the exhibition however they wish. The second floor has been transformed into a slightly mad version of a 19th century Russian parlor, with floral wallpaper, corrugated columns, and a comfortable settee. This is the home, as it were, of Gogol’s characters: old-fashioned and a bit crazy.

Chagall’s illustrations of characters and events line the walls with quotes from the novel. We see Chichikov, the mysterious buyer of dead souls, being born and not being quite what was expected. We are introduced to the dreamy and sentimental Manilov (whose name is derived from the word to lure); the widow Korobochka (“Little Box”) who runs her small farm well but has no loftier spiritual interests; Nozdrev (“Nostril”) who is hearty and hail-fellow-well-met while being a cheat and a bully; Sobachkevich (“Dog”) who is solid, simple and interested in making a deal and money; and Plyushkin, the miser and hoarder, sadly collecting useless bits and bobs.

“The Prosecutor’s Funeral,” Marc Chagall, 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. Fridman

“The Prosecutor’s Funeral,” Marc Chagall, 1948, lithograph From the collection of B. FridmanGogol draws these characters with broad strokes and a delicate pen, making them both larger than life and very detailed and specific. They are not cardboard figures, although now Russians use their names to describe people like them. For example, they might call their dreamy son Manilov or the hoarder on the fourth floor of their apartment house “a real Plyushkin.”

Chagall’s lithographs are the visual representation of the text. Some are delicately penned drawings with masses of tiny details. Others are bold and dark. Sometimes the perspective is skewed; sometimes it is perfectly rendered.

Before leaving this floor, be sure to relax on the settee and watch the characters in Chagall’s drawings in animation, projected on the fourth wall.

“Zverev Drawing ‘Dead Souls,” 1950s From the collection of S. Alexandrov

“Zverev Drawing ‘Dead Souls,” 1950s From the collection of S. AlexandrovThe third floor presents Zverev’s illustrations and portraits of Gogol. The décor is black and white, with plain block benches. But the severity is just a foil for Zverev’s watercolors, which are exuberant splashes of color, and the fun-house mirror in the corner. Walk closer to see Zverev appear to pop out, holding portraits and jesting.

The exhibition is accompanied by a rich series of films and discussions in Russian, described in a brochure found in stands on the stairwells.

The show will run until August 18.

AZ Museum. 20-22 2nd Yamskaya-Tverskaya Ulitsa. Metro Mayakovskaya. For more information, see the website.