A new play has opened in London’s Marylebone Theatre on a theme that might seem jarring in these times: coerced Jewish collaboration in the Holocaust. Yet “The White Factory” remains one of the year’s most compelling plays.

First-time playwright Dmitry Glukhovsky is better known for his futuristic dystopian novels about survivors of a nuclear holocaust who live in the tunnels of the Moscow Metro. Maxim Didenko, an award-winning theater director and choreographer from St. Petersburg, directs the show, rendered in English by renowned translator Marian Schwartz.

Six years ago Glukhovsky was reading Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” when he stumbled upon the idea that became this play. It was the story of SS commander Wilhelm Koppe, implicated in killing 340,000 people: mostly Jews but also Roma and Polish partisans who lived in or around the city of Łódź in Poland. Koppe escaped persecution for his war crimes, becoming the head of a Chocolate Factory after the war.

Glukhovsky relates how he travelled to Łódź many times, visiting the former Jewish ghetto which is still there, “well preserved and yet forsaken.” He saw that ethnic cleansing was something in living memory that could be repeated all too easily.

In the two-act play we follow idealistic lawyer Yosef Kauffman as he bargains with the Nazi occupiers in Poland’s Łódź ghetto and then struggles to rebuild his life after the war. Kauffman and his family are fictional, but historic figures like Wilhem Koppe also appear on stage. Chaim Rumkowski, a Jewish orphanage boss who became the unwilling overseer of the ghetto, is played by Adrian Schiller, himself the descendent of Holocaust survivors. Rumkowski encourages the people of the ghetto to make themselves “indispensable” to the Germans by working in the factory.

Describing the Łódź ghetto, Glukhovsky told The Moscow Times that, “The Jews had to turn a Catholic church into a factory to recycle the pillows taken from people sent to death. The new pillows went to Germany, so that German families would have a sweet sleep on them. The feathers and the goose down were flying to the ceiling, and the church was renamed ‘the White Factory’.”

His script became starker following a conversation with a Holocaust survivor he met in New York. “The reality of what was happening, he adds, “was much stronger than any metaphor I could come up with.”

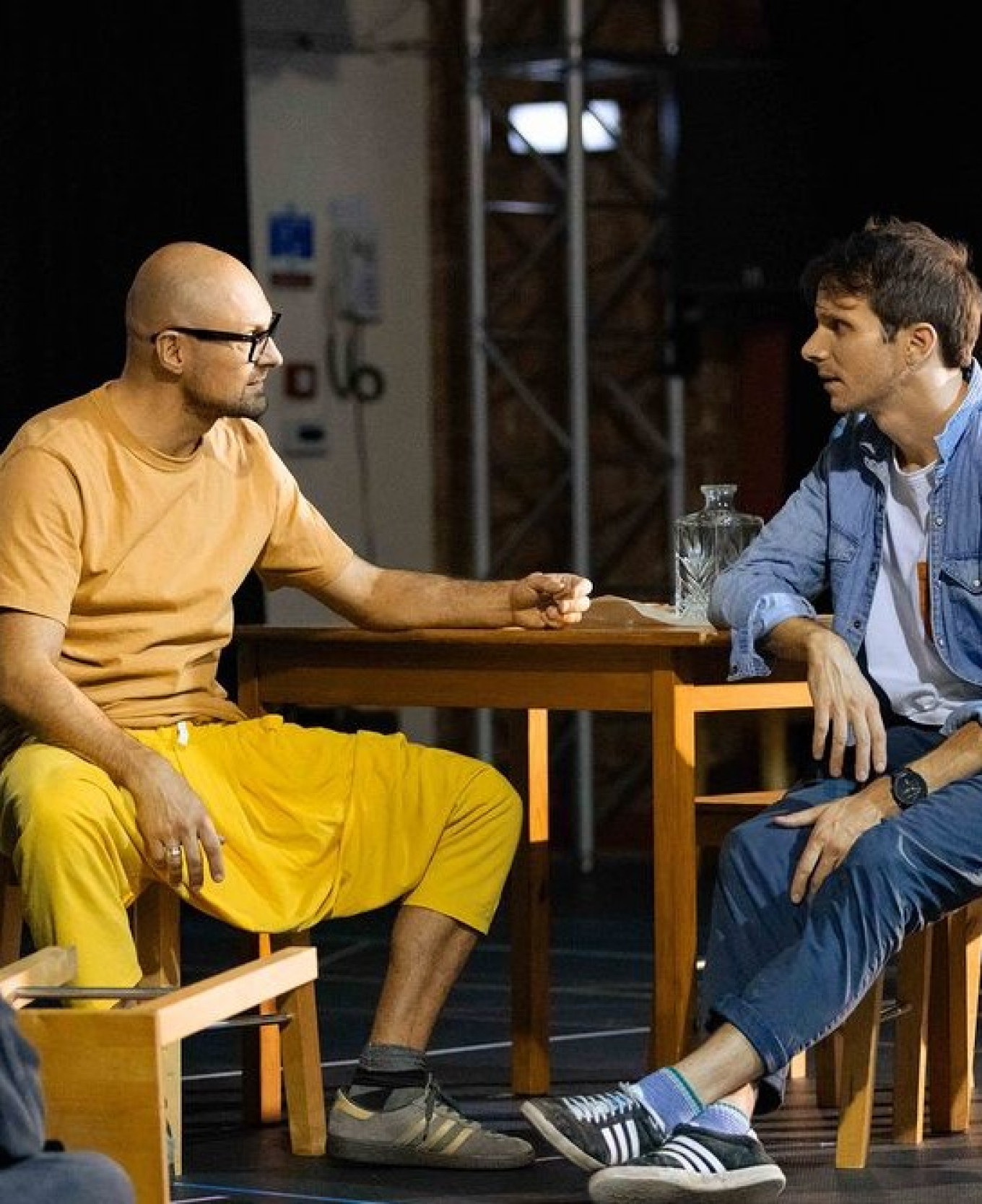

Director Maxim Didenko has opted for simplicity at the small theatre some distance from London’s West End. The audience sees the sparsest of props: sacks of feathers, a jug of water, and a white cube whose vertical walls double as beds in the play’s claustrophobic domestic scenes.

On stage the details of 1940s Poland are lightly sketched; this is also a universal story about a trapped family – a grandfather, father, mother, and two boys.

Throughout the play, an on-stage cameraman films the actors. Didenko told The Moscow Times that the Germans used to photograph and film what happened in the Jewish ghettos. “I saw a documentary based on home videos by [Hitler’s girlfriend] Eva Braun. And another by the personal cameraman of [Hermann] Göring.”

Didenko wanted the play to become a documentary in its own right. “After all, these things happened just 80 years ago.”

The child actors give touching performances that never feel forced; Glukovsky drew on his own family life when writing the dialog. A pivotal episode in the history of the children of the Łódź ghetto is also portrayed in “The White Factory.” As Nazi quotas become stricter, commander Koppe pressures Rumkowski to send thousands of “unproductive” child-workers in his factory to their deaths. Unable to save everyone, Rumkowski is reduced to bargaining to raise the cut-off age. “Five? Six, then? Seven?”

“Do you think I don’t know what a seven-year-old child is like?” snaps the Nazi commander. “I have young children myself,” he adds to shocked silence in the auditorium.

On the wanted list

Glukhovsky has previously crossed swords with the Russian government over his support for dissident Alexei Navalny. When Russia invaded Ukraine, he left the country and spoke out against the war; by June he was on the Russian federal wanted list for “discrediting the Russian Armed Forces.” He was tried and convicted in absentia with an 8-year prison term.

“When Russia’s war in Ukraine began,” Glukhovsky said, “I had to do another three rewrites [of the play] because I changed my understanding of how we get used to evil. And about how we find ourselves able to join the evil. How do we justify ourselves when we cede to the pressure of a great strength? And what do we become?”

Glukhovsky said the play isn’t about ideology. “I’m more interested in tracing changes these choices and unnatural compromise are causing us to make,” he told the Moscow Times.

As for the threatened prison term, the writer saw this as an “almost inevitable” result of his comments.

Translator Marian Schwartz tells The Moscow Times that her work with Glukhovsky began in 2018, when he asked her to translate some of what he called his “literary fiction.” She translated two stories, “Oppenheimer” and “Sulphur.”

“When I was first reading Dmitry’s short stories, he sent me an earlier version of ‘The White Factory’.” She also saw the invasion of Ukraine as a turning-point in the play’s journey to the stage. “The story of a regime’s victims facing the excruciating dilemma of trying to resist evil, whether actively or passively, took on a resonance it hadn’t before,” she noted.

“Five years ago” Didenko comments, “it was difficult to touch this topic, because it’s so fragile…[Actor] Adrian Schiller’s father was wearing a [yellow] star as a child, and then spent time in a camp in London because he was an Austrian citizen. So it was a sensitive topic for him too, and it took him some time to say yes to us.”

Didenko, who left Russia when the war began, also talked about guilt. “I think we all are responsible, but who is guilty? People who push the buttons to send rockets to civilians. When you are guilty, you are frozen, and when you are responsible, you act. So my action is my art.”

He added: “I can’t judge my people who didn’t have the possibility to run away. But the play relates much to myself and to my friends who live in Russia now.”

“The White Factory” is playing at Marylebone Theatre in London until November 4.