Leo Tolstoy liked to take long walks. He would sometimes leave the estate and walk wherever his fancy led him. One day he wandered from Yasnaya Polyana to the railway station, where a train was standing under billows of steam, ready to leave. Suddenly, a pleasant-looking lady stuck her head out of the window and said: “I say, man, go to the ladies’ room for me — I left my purse there”.

Since he was asked, Tolstoy went where he was told. And why not? He was curious about the ladies’ room. He got the purse and handed it to the lady through the window. She tipped him a five-kopek piece “for tea.”

Well, that was awkward. Tolstoy used to buy tea for 2 rubles 50 kopecks a pound in a shop. But he wasn’t above taking the coin.

But where did the expression “for tea” come from? The source is none other than Tsar Alexander II, who began the fashion for tea houses in Russia. These institutions were encouraged by the authorities not as “public catering facilities” but as places that would “cultivate culture.” Tea houses did not serve vodka or other alcoholic beverages. People could drink their tea and read a newspaper or take part in refined conversations.

Naturally, the nobility and the well-to-do did not go to tea houses. But they encouraged this movement as a way of taking care of the “common people.” So the lady in the train gave a five-kopek coin not for a glass of vodka, but for hot tea.

But on the train someone told the woman, “That’s Count Tolstoy who did a favor for you, madam.” Her panicked screams echoed across the platform, “Lev Nikolayevich, Lev Nikolayevich, give me back my coin! I didn’t recognize you!”

In reply, Tolstoy muttered: “No, I earned it.” And he put the coin in his pocket. After his long walk he used it to buy tea and drank it with great pleasure.

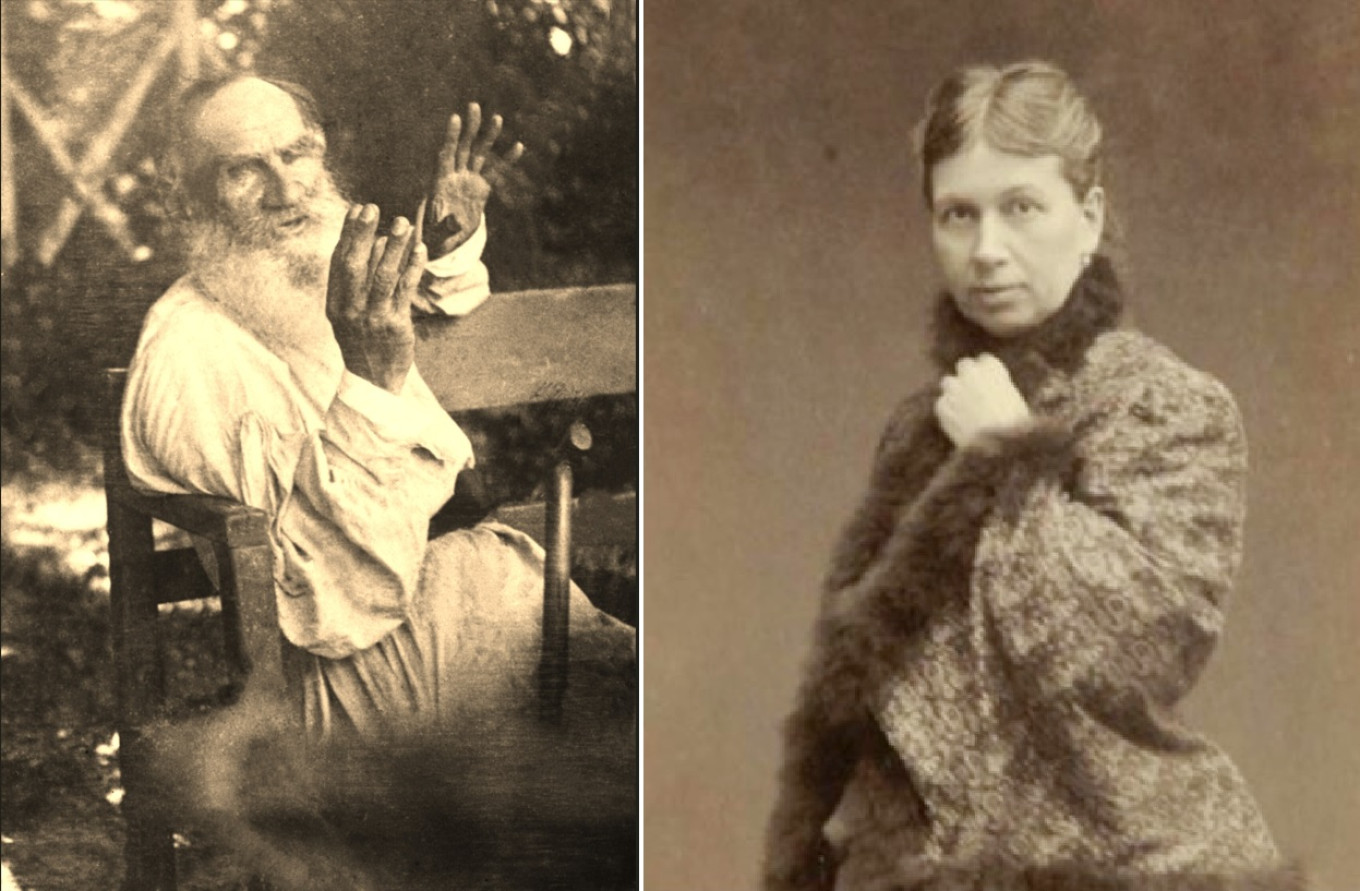

Tolstoy loved tea. He said that it “liberated the forces and possibilities that slumber in the depths of my soul.” He drank up to 25 glasses of tea a day. His wife Sophia didn’t want to constantly bother the servants to deal with the samovar, so she heated his tea on a spirit stove. “You should have married Robinson Crusoe,” Tolstoy said, looking at her heating system. “Yes, it would have been better to marry Robinson,” Sophia probably thought to herself, weary of her husband’s eccentricities.

Tea at the Tolstoy’s was filled with surprises. Imagine you are Countess Tolstaya. You enter the living room, where your invited guests from high society are expecting you. The table is set for tea, the candles are lit, but there isn’t a soul. And then suddenly before the astonished eyes of the hostess, there is a bark of laughter and the “high society” lifts the tablecloth and comes out from under the table. This was, of course, her husband’s idea…

Tolstoy invented another game for those occassions when a dull and rather unpleasant guest finally left. Tolstoy wouldn’t allow anyone to speak badly of the visitor, but he didn’t hide his feelings. As soon as the guest walked out the door, everyone at the table jumped up, raised their right arm and galloped through all the rooms on the first floor with serious expressions. They would run back to the table and only there would they start laughing. Tolstoy called it the March of the Numidian Cavalry.

That’s what tea does to people…

Since childhood we have thought of Leo Tolstoy as an ascetic, not at all interested in the delights of the table. Many have read about his commitment to vegetarianism and simple peasant food. But this was not always the case in his life. And the young man who inherited Yasnaya Polyana at the age of 19 traversed a long moral path before leaving the estate forever at the age of 82.

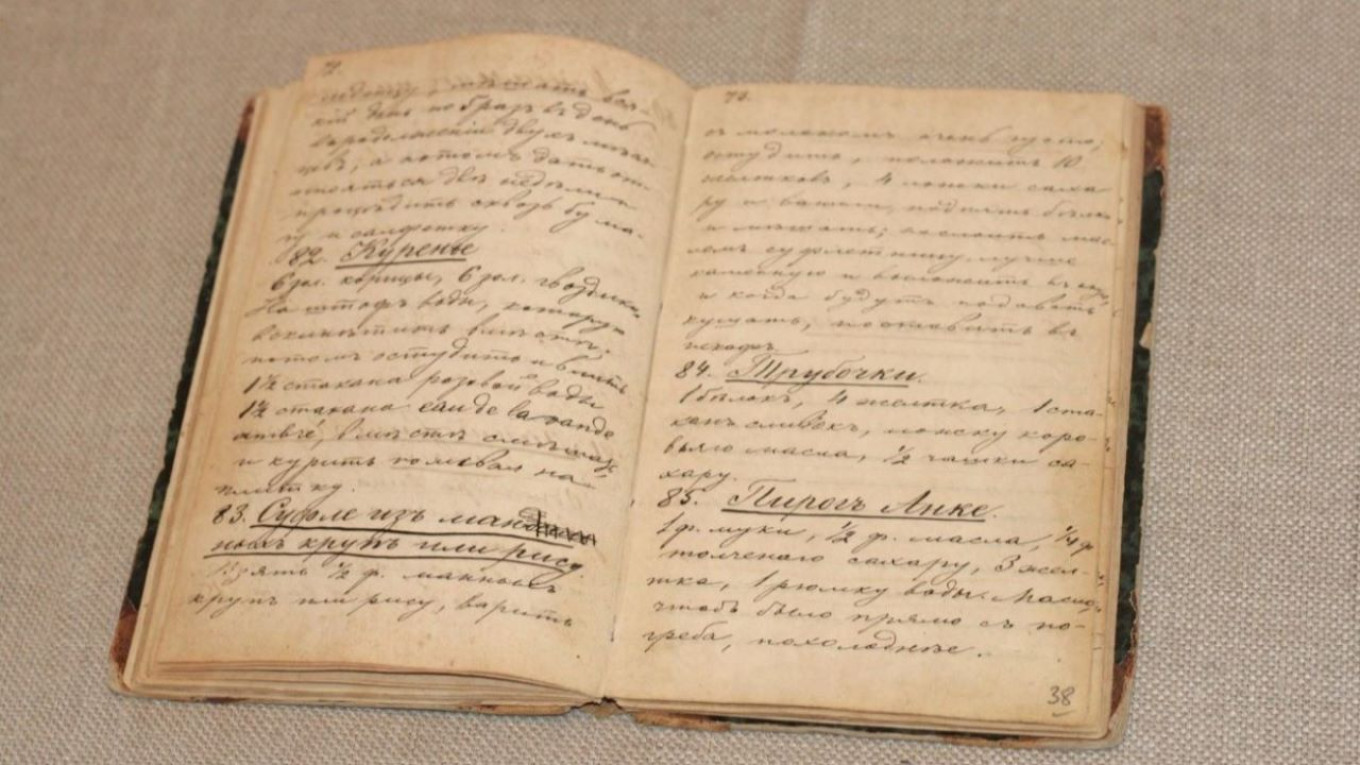

And yet, Yasnaya Polyana is most closely connected with the family’s best culinary traditions. Here Sophia, Tolstoy’s wife, stood by his side and later left us with her amazing “Cookbook.” Only in October 2013 was it taken out of the legendary Steel Room — a carefully guarded room on Prechistenka in the center of Moscow where Leo Tolstoy’s manuscripts are kept. Until then, it had not seen the light of day for almost a hundred years. The manuscript had lain in the archives, and it could not be printed during the author’s lifetime. Only a small and incomplete edition was published in the 1990s. In 2013, it was once again presented to the public at the Yasnaya Polyana Gallery in Tula. And thanks to the efforts of the staff of the estate museum, we were able to publish its new edition, complete with our detailed commentary.

A little over a century has passed since the days of Tolstoy and his family — a blink of the eye by historical standards. The cuisine of that period seems very familiar to us. Why? Perhaps because the entire family was characterized by simplicity and sincerity. We won’t find the pretentious dishes of haute cuisine of the time, such as Boeuf Mironton, truffles or Cutlets à la Maréchale. Instead we find ordinary, everyday dishes: dumplings and scrambled eggs, lemon tart and potato pudding, mushroom soup and gingerbread. We don’t even need to recreate them — they are part of our lives today.

These records can hardly be called a cookbook in the usual sense of the word, as there are no sections on “salads, soups, hot dishes, desserts,” nor the usual introduction on “how to make broth.” There aren’t even many recipes — just 162. But here’s the paradox. Each one is not just a list of products, pounds, and minutes. Many have a story and names of their own. “Maria Nikolayevna’s Apple Kvas” is from the writer’s younger sister. “Marusya Maklakova’s Lemon Kvas” is from a close acquaintance of the Tolstoy family, whose brother, a famous lawyer and leader of the Cadets, would become a “white emigrant” after the revolution. “Bestuzhev’s Easter Curd and Cream Mold” is from V. N. Bestuzhev-Rumin, who was chief of the Tula Armory 1876-79. The “Apple Confections of Mar.Petr.Fet” recipe came to the family from Afanasy Fet’s wife. And “Perfilievs’ Sparkling Wine” came into the household from Leo Tostoy’s third cousin.

This is living history. Behind each of these recipes is an episode or a whole page of Russian cultural life.

Here is one of our favorite recipes, Sophia’s Almond Cake. It can be made in ramekins —small muffin tins (as pictured above) — or in a large round cake tin.

Tolstoy’s Favorite Almond Cake

Ingredients

- 9 eggs

- 200 g (1 c) sugar

- 200 g (2 c) ground almonds

- pinch of salt

- oil and crumbs to grease and crumb the mold

- Vanilla and almond extract as flavoring

Instructions

- Prepare the cake tin(s): grease it with butter and sprinkle with crumbs.

- Preheat oven to 175°C /350°F.

- Separate the whites from the yolks. Whisk the yolks with the sugar until pale and thick.

- Whip the whites with a pinch of salt until they form a stiff foam.

- Add half of the ground almonds to the yolks, mix gently and gently fold in half of the whipped whites.

- Add the remaining ground almonds and whipped egg whites.

- Thoroughly but gently fold in the whipped egg whites without “breaking” them.

- Pour into baking dish(es) and bake for 40 minutes.