In October 1917, Lenin’s Bolshevik Party seized power and inaugurated the first communist workers’ state, founded on the principles of Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital.” Almost immediately, the race was on to turn antiquated, almost feudal imperial Russia into a communist utopia. It was a tall order in Russia: the vast majority of the population of the nascent Soviet state were illiterate peasants, for whom the traditions and tenants of Orthodox Christianity were the sole cultural and spiritual bedrock. Replacing it with the more complicated economic and social principles of Marxism took ingenuity, dedication and ruthlessness.

The state embarked on a nationwide campaign to discredit all deities, confessions and religious traditions throughout the former empire. They closed all religious-affiliated schools, closed monasteries and sanctioned wholesale destruction of church property. The effort would span decades until it simply ran out of steam in the 1980s. But at its height, the anti-religious campaign was a highly effective arm of the state, which harnessed a powerful medium — graphic art and the propaganda poster — to communicate its core message that religion had no place in communist life.

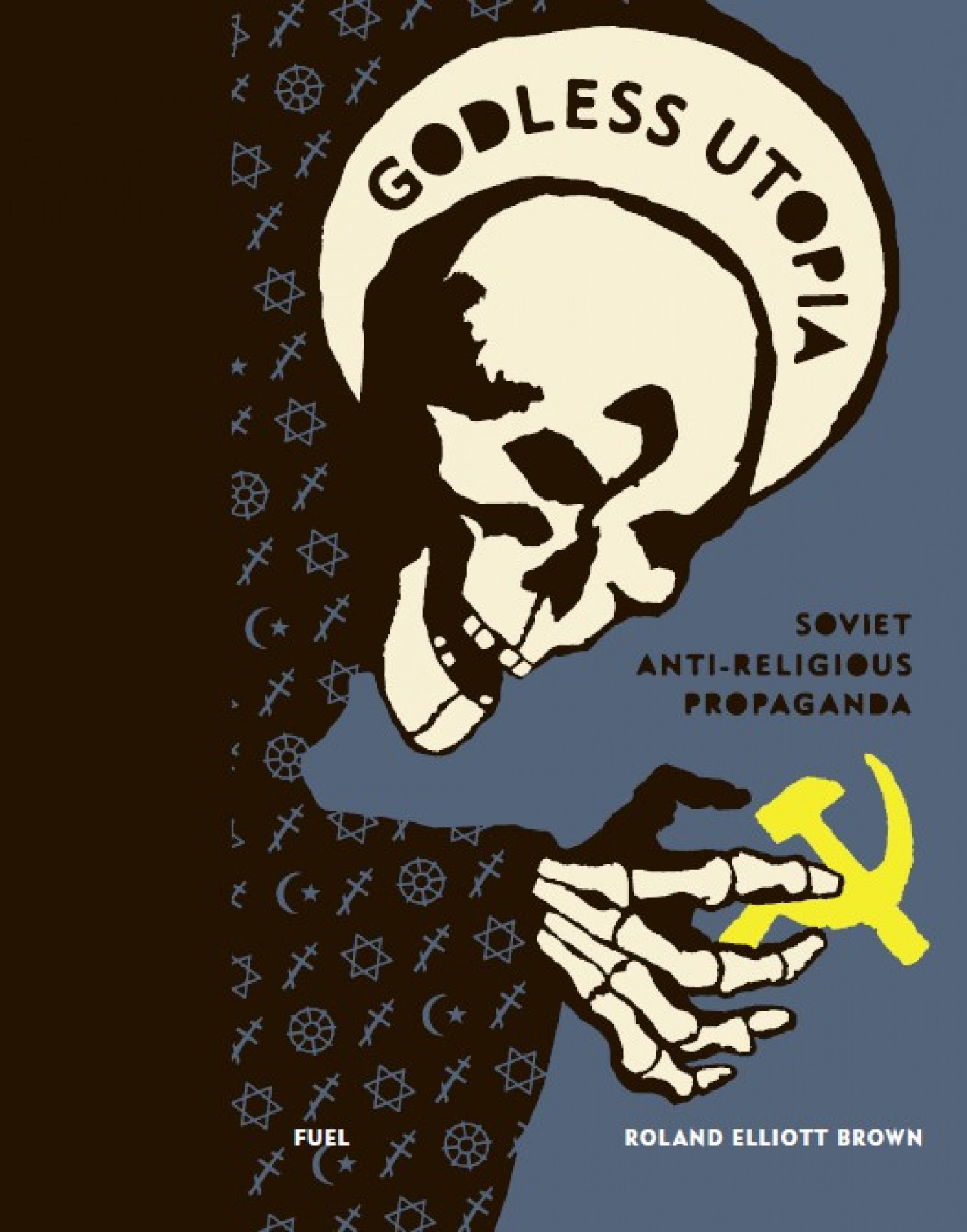

The anti-religious campaign and its vibrant iconography is the subject of “Godless Utopia: Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda,” a fascinating new book by Roland Elliott Brown, published by Fuel Design & Media, which examines the anti-religious campaign through a collection of illustrations, posters, and the cover art of two prominent atheist magazines. The illustrations are accompanied by full translations of their slogans, but it is telling that these are almost superfluous, so compelling are the images of idealized Soviet workers doing battle with, and eradicating outmoded representatives of the Orthodox Church, Judaism, Buddhism, and to a lesser extent, Islam.

Brown begins by skillfully guiding the reader through the critical milestones of the history of the Orthodox Christian Church in Russia, noting that its beginning was as violent as its supposed end: when Grand Prince Vladimir baptized Russia at the point of a sword and burned the pagan idols in Kyiv to show that recidivism would not be tolerated. This theme of church and state continues through the medieval occupation of the pagan Tatar Mongols to the rise of the Muscovite State and on to Peter the Great, who significantly diminished the Church’s power by relegating it to the status of a government department. This concise history perfectly sets the stage for the carnage to come; “Godless Utopia” charts the violence against church property, priests, nuns and religious institutions during the 1920s and 1930s.

World War II offered the Russian Orthodox Church a brief respite and a window of opportunity to show that it could walk the ethically thin line of a loyal servant of the Soviet state and faithful Christian. Brown then traces the downward trajectory of the anti-religious campaign as the country limped towards its own demise. The resurgence of the Church is charted through its very public rapprochement under Gorbachev, ideally timed to coincide with 1988 and the Millennium of Grand Prince Vladimir’s baptism.

In “Godless Utopia,” Brown gives us much to consider about the nature of man’s relationship with both church and state. “Godless Utopia” examines the anti-religious campaign of the Soviet Union in its entirety as a separate political and social phenomenon, and does so very effectively through the lens of its primary communication instrument: graphic art. The result is a beautiful volume of illustrations and images as disturbing as they are thought-provoking — particularly so now, when the world is witness to a new resurgence of religious intolerance.

Students of Russian history will welcome the publication of “Godless Utopia” this month, but so too will art historians, religious scholars, as well as observers of Russia’s cultural history and indeed anyone who has embarked on the quixotic search for the elusive Russian soul.

“Godless Utopia: Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda,” from Chapter Three “Priest of Power”

Mikhail Bulgakov’s great novel of Stalin-era Moscow, The Master and Margarita, begins with a debate between two atheist propagandists. The older, more learned Berlioz is lecturing a crude young poet, who goes by the pen-name ‘Homeless,’ about the failure of his latest submission. Homeless has depicted Jesus as a villain, but this, Berlioz says, is not the point. Since Jesus never existed, Homeless ought to show how the myth of Jesus evolved from the myths of even more ancient gods like Osiris and Mithras. Into their conversation steps the devil himself, in the guise of a weird tourist, and enquires whether both men are atheists. Berlioz gives him the party line: “In our country atheism doesn’t surprise anyone. The majority of our population consciously and long ago ceased believing in the fairy tales about God.”

Bulgakov, who wrote his novel in secret during Stalin’s Terror in the 1930s, had picked up on the quarrel that began between atheist propagandists around the time of Lenin’s illness and death. The two leading anti-religious magazine editors of the era, Emelian Yaroslavsky and Maria Kostelovskaya, despised each other and fought to dominate atheist publishing. Yaroslavsky—a ‘culturalist’ interested in the mythological and social roots of religion—was ostensibly the more learned of the two, although in practice, they covered very similar territory. Following their clash over use of the title Godless, Yaroslavsky opened a new front against Kostelovskaya by releasing his own illustrated magazine, Godless, in 1925.

One can imagine Ivan Homeless publishing his work successfully in one atheist magazine only to come up against what passed for the rival philosophy at another. Bulgakov suggests that Homeless is unfamiliar with religion, and hints that he is perhaps typical of the naive atheists who grew up after the revolution. He bears no resemblance to the seminarians-turned-atheists who influenced the Russian Marxists, and his threadbare nom de guerre suggests the previous generation of revolutionaries has already taken all the best names. The Georgian ex-seminarian Ioseb Jughashvili, for example, took ‘Stalin,’ or ‘man of steel.’

Stalin’s native Georgia was home to an ancient Christian civilization whose conversion predated Russia’s by hundreds of years. Its vulnerability to two Muslim empires—the Ottoman and the Persian—had forced it to accept Russian domination. Russia had dissolved Georgia’s ruling dynasty and replaced its independent Orthodox patriarch with a Russian. Stalin, born in 1878, went to a church school and sang in a choir. At sixteen, he entered the Tiflis Theological Seminary, where tsarist monks’ efforts to efface Georgian culture stoked nationalist resentment.

Shortly before Stalin joined, another student had murdered the rector with a Caucasian dagger. The students circulated secret newspapers and banned European novels—Victor Hugo was a favorite—and formed secret discussion groups. The young Stalin, a nationalist poet with some talent, made an enemy of David Abashidze, a Georgian monk who was even more contemptuous of Georgian culture than the Russians were. Abashidze ran a monastic surveillance regime and sent Stalin to a punishment cell for possessing banned books. Stalin later recalled the monks’ ‘spying, penetrating into the soul.’

Although Stalin spent four years there, he never graduated. He fell under the influence of a local priest’s son and rebel named Lado Ketskhoveli, who had been expelled from the Tiflis seminary for leading a student strike, and from another one in Kiev for possessing banned books. Ketskhoveli joined a group of Marxists and became a typesetter for their press. From around 1898, Stalin began to idolize Ketskhoveli and kept a portrait of him in his seminary cell. He then joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party when it formed that year. The seminary, he later claimed, expelled him for ‘Marxist propaganda.’

Historians have used Stalin’s seminary background to foreshadow his ascent as a dictator. Describing his role at Lenin’s funeral, Richard Pipes writes, “Stalin delivered a funeral speech with a ‘pledge’ in which, using religious cadences he had learned in the seminary, he vowed in the name of the Party faithfully to carry out Lenin’s commands.”

Explaining how Stalin used his position as general secretary of the Communist Party to sideline rival Bolsheviks after Lenin’s death, Geoffrey Hosking writes, “He had a crude but lucid mind, which sorted out people and political tendencies into unambiguous dualities, right/wrong, progressive/reactionary, for us/against us. He deployed his arguments like a seminarian his catechism, by question and answer and by accumulation of evidence, until he could sweep away the ‘wrong’ side of each duality with overwhelming logic.”

Even before Lenin died, the main effect of anti-religious spectacles had been to demonstrate that the ‘propaganda’ struggle between religion and atheism was to be one-sided and that the Communist Party was well and truly in charge. As the newspaper Izvestia reported on an anti-Christmas parade in Moscow, in January 1923 “God-fearing Moscow philistines saw an unprecedented spectacle. From the Sadovaya to the Square of the Revolution there stretched an unending procession of gods and heathen priests…Here was a yellow Buddha with contorted legs, giving the blessing … And the Babylonian Marduk, the Orthodox virgin, Chinese bonzes and Catholic priests … A Russian priest in his typical stole, offering for a small price to remarry anybody. And here is a monk sitting on a black coffin containing saints’ relics: he, too, praises his wares to the undemanding buyer.”

As former socialist-turned-theologian, G. P. Fedotov, reported on a similar Easter procession in Tiflis that spring: “The population, and not only the faithful, looked upon this hideous carnival with dumb horror. There were no protests from the silent streets—the years of terror had done their work—but everyone tried to turn off the road when they met this shocking procession … There was not a drop of popular pleasure in it.”

Politically, the Bolsheviks had cornered the church. When Patriarch Tikhon died compliant in 1925, the clergy did not dare to elect a new patriarch. But the placeholder, Metropolitan Sergei, pledged loyalty to the U.S.S.R. in 1927 as “our civic homeland, whose joys and successes are our joys and successes and whose setbacks are our setbacks.”

Stalin defended the crushing of the church to foreigners. Meeting a delegation of American trade unionists in late 1927, he contrasted Soviet ‘freedom of anti-religious propaganda’ with cases such as recently occurred in America in which Darwinists were prosecuted in court.

He was referring to the 1925 Scopes ‘monkey’ trial, in which a high school teacher, John T. Scopes, had faced charges for breaking a Tennessee law against teaching evolution. Scopes was fined $100, but the state supreme court overturned the verdict on a technicality. Since the Communist Party stood for science, Stalin said, such cases ‘cannot occur here.’

More substantial—and ominous—was his appeal to class warfare: “The Party cannot be neutral towards the bearers of religious prejudices, towards the reactionary clergy who poison the minds of the toiling masses. Have we suppressed the reactionary clergy? Yes, we have. The unfortunate thing is that it has not been completely liquidated.”

His answers to the Americans—and his omission of the right to ‘religious propaganda’ mentioned in the constitution—prefigured the new, Stalinist style of state atheism.

At the same time, Marxist-Leninist prophecies were failing to come true. There had been no successful communist uprisings in industrialized Europe to provide the USSR with powerful allies, and the advanced European powers remained enemies. As early as 1925, Stalin settled upon the goal of ‘socialism in one country’ and succeeded in wrenching the revolutionary project away from the emphasis on world revolution dear to Lev Trotsky—whom he expelled from the Party in 1927. But if the Soviet state was to fortify itself for long-term isolation, it needed to industrialise fast, because, as Stalin later said, ‘those who fall behind get beaten.’ To do that, it needed grain to feed the cities and export for cash.

Stalinist atheism took shape on the ‘grain front’. Responding to food shortages in 1928, the government began to seize grain. When the peasants rebelled, the regime blamed ‘kulaks’—more prosperous peasants—and, in 1929, unleashed class war in the countryside. The plan was to divide the peasantry by setting the majority of ‘poor’ and ‘middle’ peasants—against the kulaks. They would press the first two groups, along with their assets, onto state-controlled collective farms. They would dispossess and exclude the kulaks, exiling those they deemed ‘malicious’ on cattle wagon journeys to remote regions, which often led to their deaths.

Note: For ease of reading, footnotes have been removed from this section and the text formatted for this site.

Excerpted from “Godless Utopia: Soviet Anti-Religious Propaganda” published by Fuel Design & Publishing.

Copyright © 2019 by Roland Elliott Brown. Used by permission. All rights reserved.