Many believe that the COVID-19 pandemic is firmly in the rearview mirror, but this is clearly madness. I’m still in full lockdown and in deep danger of becoming something I never imagined: a homesteader. I spent much of the spring baking bread and early summer brewing kvas, and now in high summer it’s time to take on the range of Russian dairy products.

Yogurt was my entry point; more from a sense that my if daughter’s recent smoothie habit continued (and it showed no signs of abating) we would soon have to declare bankruptcy. Casting a desperate glance around my kitchen, I suddenly realized that I had the means to go into yogurt and whey production with almost no overhead. My trusty Instapot (multi-cooker or “steamy pot” depending on what part of the English-speaking world you’re from) has a yogurt function. With very little research and almost no hands-on work, I was soon producing kilos of high-quality Greek yogurt, labneh, and enough whey (the liquid by-product of any fermented dairy product) to satisfy even the most voracious smoothie habit.

Turning to tvorog

After an unsuccessful foray into kefir production, I turned to tvorog, which seemed, on the surface of it, a far simpler prospect and one that also held out the promise of saving tons of money: my husband consumes about a pint of tvorog while he is waiting for the coffee water to boil. Every day.

When I first arrived in Russia in the early 1990s, tvorog was one a long line of baffling Russian products I could not understand.

Its packaging (bland industrial blue and white tin foil) offered no hints. I knew it was some kind of dairy from its location in the sour-smelling dairy aisle. Being new to Russia, I naively asked a shop assistant with an absurd conical hat and fluffy neon blue apron what it was, and she looked at me as if I were lacking a chromosome or eight.

I was none the wiser when I took the moist square packet home and opened it up. It looked like ricotta but had none of ricotta’s smooth creaminess. It was not yogurt, and it had none of the texture of any cottage cheese I had every consumed. It was drier and far sourer, and I could not for the life of me work out how one might consume it or use it in a recipe. I shoved it to the back of the fridge and forgot about it.

Over the next decade, understanding trickled into my consciousness. I got to know a lovely dairy woman at Leningradsky Market who made and sold a wildly popular homemade tvorog. This was creamy and light but incredibly filling, delectable just on its own, superb when spiked with fresh herbs, or magnificent alongside Russian penicillin (otherwise known as raspberry jam).

Explaining tvorog to the outside world remains a challenge. We often describe it as “Russian cottage cheese,” but this is erroneous, as thousands of emigres who patiently strain cottage cheese to approximate the dryer consistency of tvorog can attest. Classic cottage cheese is made with animal or vegetable rennet, whereas tvorog is made with conventional acids, such as lemon juice, vinegar, or buttermilk. This makes both quark and farmers’ cheese better analogs. Nor is tvorog “Russian ricotta,” though its texture is closer to the Italian soft cheese made from whey and milk. Tvorog’s small and easily shaped curd may well be the clue to its name, which probably comes from the Old Church Slavonic word “tvor” meaning “to form.”

Tvorog is the pillowy dairy comfort food of Russian childhood. The gateway drug to tvorog is syirki: addictive, chocolate-covered logs of sweet tvorog, called by its Russian diminutive tvorozhok. Because tvorog is a fermented product, it is often easier to digest than other dairy products and thus force fed to kids in Russia until they either get married or go off to do their military service.

Tvorog is consumed on its own, with berries or jam, or in one of several classic Russian dishes: vatrushki are sweet pastries with tvorog in their middle, which cross the Atlantic at the beginning of the 20th century and become cheese Danish. Tvorog is also a favorite filling of Ukrainian varenki, or sweet dumplings.

And it’s the key ingredient in the annual show-stopping Easter paskha, where tvorog is mixed with equal parts of butter and sugar and candied fruit for an intensely rich end to the long Lenten fast. It came as no surprise that many culinary historians believe that tvorog is the great-grandparent of that quintessential American phenomenon, the cheesecake.

Like most Russian foods, the best tvorog made at home by your babushka (or better still, at her dacha). But babushka is unlikely to stop there: tvorog came into being because it was a better way to preserve raw milk. But even tvorog won’t last forever. To make sure it doesn’t spoil, babushka will probably parlay tvorog on the turn into syirniki or cheese pancakes, also a staple of Russian childhood, which have found their way into mainstream cuisine as a popular dessert.

The many ways to make tvorog

The chemistry of tvorog seems straightforward. All you need is milk, some kind of acid, salt, and optional cream or buttermilk. The acid is introduced into the warmed milk, which immediately curdles, forcing the milk curds to separate from the whey. You leave this alone for a time, then drain it, and mix with a bit of optional cream and some salt and that’s tvorog. (Don’t discard the whey — see the sidebar for great ways to use it!)

Simple, right? Wrong. The key variables of milk temperature, type of acid, and length of curdle offer infinite possibilities. I wanted a recipe that would be almost as hands-free as my yogurt method. Once again, the Instapot multi-cooker was a godsend, allowing me total control of the temperature of the milk, which needs to be just under boiling.

My time fiddling in the Tvorog Test Kitchen produced industrial quantities of tvorog, more than a regiment of Russian husbands can consume. There was nothing for it, it was time to perfect my syirniki recipe, or Russian cheese pancakes. Classic syirniki use an even ratio of tvorog to flour (or sometimes very little flour) with an egg to bind it; this results in a dense texture, like fried cheesecake. Since syirniki are usually paired with fresh fruit, I cut the sugar back dramatically. Inspired by “The Pancake Handbook: Specialties from Bette’s Oceanview Diner,” I upped the number of eggs considerably and whipped the egg whites into stiff peaks, which achieves an unthinkable lightness. The addition of buckwheat flour adds a nutty flavor element, while buttermilk or kefir injects a pleasant tangy note. Light but flavorful, these syirniki are perfect for breakfast or brunch, paired either with fresh fruits or smoked fish.

Tvorog

Ingredients

- 4 quarts (4 liters) whole milk

- 6 Tbsp (70 ml) white vinegar

- Generous pinch of salt

- ½ cup (125 ml) light cream or buttermilk

Instructions

- Heat the milk to 175ºF (79ºC), keeping a close eye on it to ensure it doesn’t reach boiling point.

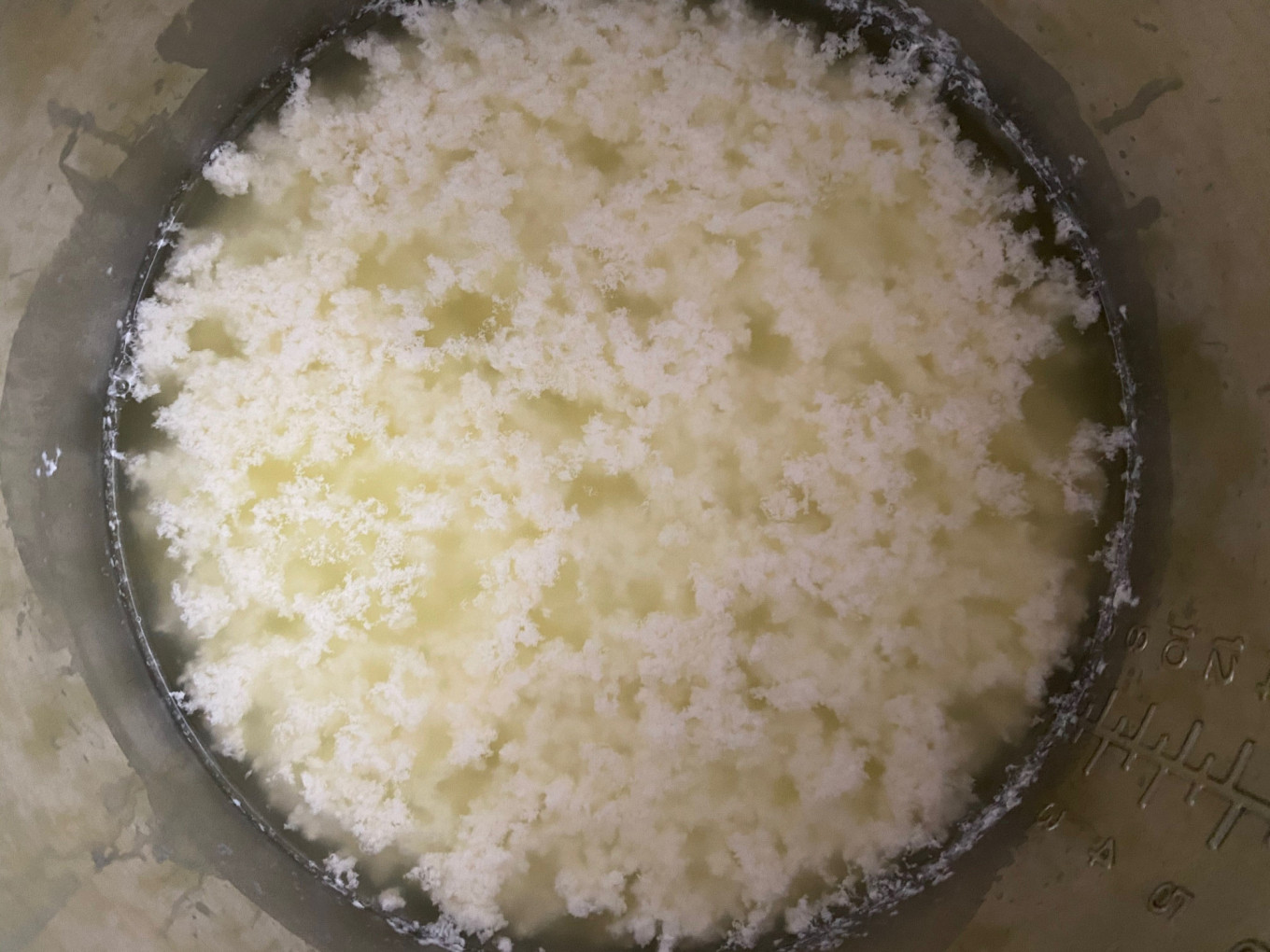

- Remove the milk from the heat and slowly, but steadily pour in the vinegar, then stir gently with a wooden spoon for 1-2 minutes. When you see hints of the curds separating from the yellow whey, cover the pot with a clean towel and a tight lid. Leave it for 30 minutes.

- While you wait, set a colander lined with cheesecloth over a large bowl or pot, which is deep enough to ensure that the contents of the colander do not touch they whey in the pot below.

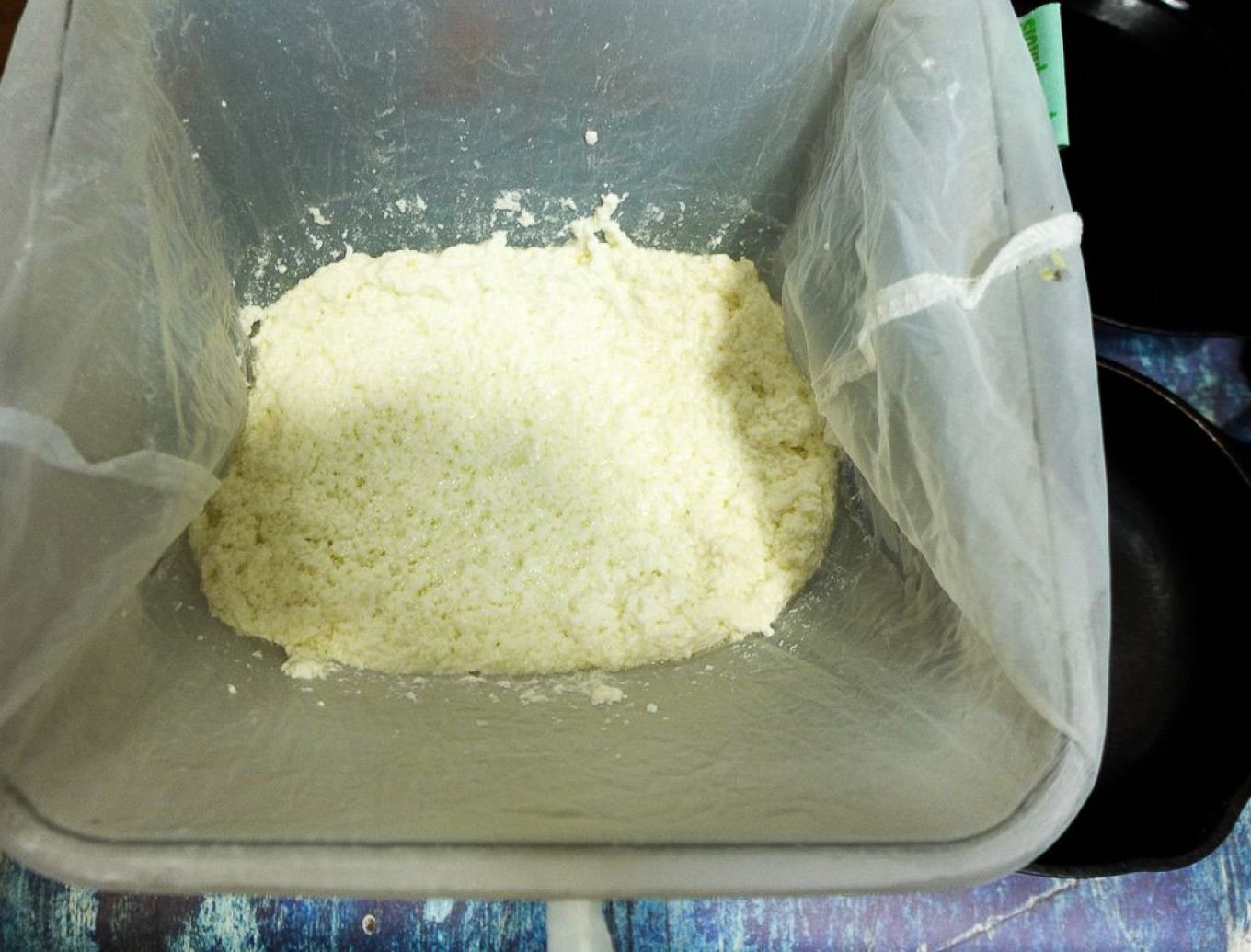

- Sprinkle salt over the mixture, then gently pour the mixture through the colander, allowing the whey to drip down into the pot. This can take a while but be patient and wait until all the whey has drained.

- Decant the tvorog into a clean, non-reactive container and mix with the cream or buttermilk to your desired wetness. Chill for at least 4 hours before enjoying. Tvorog will keep for 7 days in the refrigerator.

Syirniki (Tvorog Pancakes)

Ingredients

- 1 ⅓ cup (320 ml) tvorog

- ½ cup (125 ml) kefir or buttermilk

- ½ cup (125 ml) buckwheat flour

- ¼ cup (60 ml) all-purpose flour

- 1 tsp salt

- 1 Tbsp sugar

- 6 eggs, separated

- 1 potato, sliced in half lengthwise

- Vegetable oil for cooking

Instructions

- Separate the eggs and whisk the yolks until the color lightens slightly and the mixture feels thicker.

- Add the buttermilk to the egg mixture and whisk to combine.

- Whisk together the flours, salt, and sugar, then gently fold the egg yolk mixture into the dry ingredients.

- Beat the egg whites until they form peaks and take on a glossy color. Gently fold the egg whites into the batter until just combined.

- Preheat the oven to 200ºF (95ºC) and put a baking sheet into the oven.

- Heat a skillet (non-stick works well here) over medium heat. Pour ⅓ cup (80 ml) of vegetable oil into a shallow dish. Use a sturdy fork to skewer a potato half, then dip it into the oil and rub the potato onto the skillet.

- Scoop a scant ⅓ cup (80 ml) of batter onto the skillet and cook until golden brown (about 2 minutes per side). Keep the pancakes warm in the preheated oven.

- Serve with fresh berries, jam, honey, or smoked fish and more tvorog!

5 ways to use whey

Whey contains impressive amounts of vitamins and protein, making it an ideal nutritional supplement. If you make tvorog, keep the whey in the refrigerator and use it!

- Add it to a smoothie instead of juice.

- Use whey instead of water in soups and stews.

- Use whey to cook grains.

- Make ricotta using whey as the acid.

- Use whey instead of water when baking bread or rolls.