Writing about cookbooks should not be a minefield, but in trying to nail down exactly what constitutes a “Russian” cookbook, I often feel the need of a sturdy flak jacket. When you focus on a region whose physical and political borders have ebbed and flowed as often as Russia’s has, culinary history can well become controversial if not positively incendiary. I’m still bruised from the time I tried to join a Facebook group of Estonian cuisine buffs, only to be told to get lost when they saw my Russian surname and Moscow bylines.

There is also an “Alice Through the Looking Glass” aspect to writing about “Russian” food writers. Neither of the hipster PR girls at Moscow’s chic Danilovsky Market has heard of Olia Hercules or Anna von Bremzen, while no one in New York could pick Maxim Syrnikov (surely a nom de guerre?) out of a police line-up. Pity the writers caught in the maelstrom.

Absorbing the Cuisines of a Multi-National Empire

Russian patriotism is all the rage at the moment, but I have yet to meet a Russian— even one who sports a St. George ribbon on his dashboards— who eschews khachapuri, plov, borshch, or Latvian sprats on political grounds. Since the Mongol Tatars invaded Russia in the 13th century, bringing with them fermentation, meat on skewers, and spices, Russians have proved themselves to be uncommonly amenable to culinary imports.

As Russian colonized the hinterlands of her territory, pushing ever further east, south, and west, she absorbed the food and drink of these new territories into her own cuisine to such an extent that these regional dishes’ official provenance is now “Russian,” rather than Siberian (pelmeni), Polish (vodka), or Tatar (chebureki).

While the peasant diet changed little over the centuries, relying on traditional “low and slow” pottages, stews, and porridges cooked on the all-important stove, the nobility of Russia adopted French cuisine after the reign of Peter the Great. Thus, dishes such as Veal Orloff, Beef Stroganoff, aspics, salads, and frothy desserts entered the culinary canon.

Cookbooks in Imperial Russia began to be popular at the beginning of the 19th century, though enthusiastic culinary historians will find much to chuckle over in “Domostroi,” Russia’s venerable sixteenth-century household manual. Translations of established foreign cookbooks— mainly French and German— gradually made way for domestic Russian cookery volumes, which proved popular throughout the vast empire until the eve of World War I.

The revolutions of 1917, which ushered in the Soviet era had two major consequences for Russian culinary history. Food production inside the Soviet Union was swiftly industrialized with labor-saving innovations in refrigeration and canning. Workplace canteens became the places where food was consumed, though attempts by the government to eradicate home cooking never fully succeeded, particularly in the countryside. Outside the Soviet Union, waves of emigres brought their recipes with them to other countries. Deli food in America, for example, owes much to first-generation Russians.

The nine cookbooks I present here can be roughly divided into three groups: “classics”; the “cold warriors”; and “the new kids on the block.”

No discussion of Russian cuisine is possible without some reference to two historical books, which in many ways are the bookends of the homegrown genre. The “cold warriors” are the writers of four books, all written outside Russia either by enthusiastic foreigners or nostalgic emigres, and each is tempered with a subtle sense of melancholy that the cuisine is somehow not completely accessible to the author. Finally, three “new kids on the block” represent an entirely new era. They bring with them a fresh approach to Russian cuisine that reflects today’s more porous political borders and increased flexibility in interpreting classic dishes.

The Classics

A Gift to Young Housewives by Elena Molokhovets (Indiana University Press, 1998)

“A Gift to Young Housewives” was first published in 1861, the same year as the emancipation of the serfs. Elena Molokhovets’ cookbook proved equally revolutionary, remaining popular and in print right up to the 1917 revolution. She describes the opulence of nineteenth-century Russian kitchens, a world in which both abundant seasonal ingredients and a large labor force are assumed. After 1917, tattered copies of the book were passed down through generations of Soviet-era home cooks, who no doubt found the list of ingredients almost fantastical. Lovingly translated into English by Joyce Toomre, “A Gift to Young Housewives” is a marvelous window into the bygone culinary world of Tolstoy and Turgenev’s countryside.

Try: Pureed Fresh Cucumber Soup

The gift that keeps giving for more than 150 years Indiana University Press

The gift that keeps giving for more than 150 years Indiana University PressThe Book of Healthy and Tasty Food by Anastas Mikoyan (SkyPeak Publishing, 2012)

What Elena Molokhovets is to nineteenth-century culinary history, Anastas Mikoyan, Stalin’s commissar for foreign trade is to the Soviet era. Mikoyan’s passion project was as welcome to Soviet housewives, to whom it is dedicated, as Molokhovets’ book had been to their great-grandmothers. Containing more than 1,400 recipes, it sold more than 8 million copies and has never been out of print since it’s 1952 publication (it was first issued in 1939, but the war hindered further print editions). Many of the recipes in the Book, as it is lovingly referred to, begin with “open a tin of…” reflecting the ubiquity of tinned food, as well as the fact that many Soviet citizens were still in possession of only one burner on a communal apartment stove. The Book’s recipes contain ingredients that can be counted on the fingers of one hand and only a few simple steps. It also contains useful information on nutrition, cooking methods, and even the etiquette of setting a proper table, reflecting the post-war trend of returning to family life. Some of the Book’s recipes suggest access to ingredients that Soviet citizens found laughable, but for the social historian, it offers an invaluable window into the era of Brezhnev’s Stagnation and beyond.

Try: Shchi with Sauerkraut

The book in every kitchen. Courtesy of SkyPeak Publishing

The book in every kitchen. Courtesy of SkyPeak PublishingThe cold warriors

A Taste of Russia: A Cookbook of Russian Hospitality by Darra Goldstein (Edward & Dee, 2013)

Food plays an integral part in Russian history and literature, and there is no one better than Darra Goldstein for weaving these three narrative strands together. Each section and many of the recipes in her authoritative book include fascinating commentary from the author’s own experience or historical and literary references. This is required reading — and cooking — for any aspiring Russophile. Divided into seven chapters, each devoted to a different type of food (dacha fare, holiday feasts, etc.), the book offers classic Russian recipes as can be found in “A Gift to Young Housewives,” but well-adapted to Western ingredients. Russian foodies eagerly awaiting Goldstein’s next book, coming in 2020, can enjoy this revised edition.

Try: Sbiten (spiced honey drink)

Russian cuisine and culture Courtesy of Edward & Dee

Russian cuisine and culture Courtesy of Edward & DeeRussian Food and Regional Cuisine by Jean Redwood (Oldwicks Press, 2017)

Jean Redwood became fascinated with Russian cuisine while working in post-war Moscow at the British Embassy. The result was this little gem of a book, now back in print! “Russian Food and Regional Cuisine” is definitely of the “Book of Tasty and Healthy Food” era, but the recipes are well chosen and easy to follow. Redwood has a particular fascination with bread and pastries and has done a thorough study of both, which most Soviet cookbooks frustratingly lack.

Try: Crab & Rice Tefteli

Especially for pastry chefs. Courtesy of Oldwicks Press

Especially for pastry chefs. Courtesy of Oldwicks PressThe Art of Russian Cuisine by Anna Volokh (Macmillan,1983)

Anna Volokh’s 1983 tome is the one I still reach for when I need a definitive Russian recipe. A former food writer for Izvestia, Volokh knows her subject matter thoroughly and writes over 500 recipes with ease and grace. These are divided into fifteen chapters taking the aspiring cook from zakuska to desserts, as well as offering menus from different eras of Russian history. Volokh’s recipes endear themselves to me for their clarity and well-researched substitutions for ingredients that are hard to find outside Russia. Cooking from “The Art of Russian Cuisine” has helped me develop excellent pelmeni technique as well as keen insight into the origin of various dishes. For anyone embarking on a serious exploration of Russian cuisine, “The Art of Russian Cuisine” is a must-read!

Try: Salmon Baked in Parchment

Authentic but for Western cooks Courtesy of Macmillan

Authentic but for Western cooks Courtesy of MacmillanPlease to the Table: The Russian Cookbook by Anna von Bremzen and John Welchman (Workman Publishing Co. 1990: first edition)

This is the book I see most often on expatriate shelves, and with good reason. This 1990 comprehensive exploration of the cuisines of the former Soviet Union is an excellent introduction to each region and contains fascinating commentary on the origins of dishes and connections with the author, who is perhaps better known for her more recent “Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking.” Though von Bremzen writes fluidly and elegantly about her subject matter, I’m often left with the impression that one more round of recipe testing would not have gone amiss for many of “Please to the Table’s” more complicated dishes. That being said, I have spent many happy hours with my own batter-splattered copy of “Please to the Table” propped open on my kitchen counter and hope to spend many more.

Try: Azerbaijani Meatball Soup

A perennial expat favorite. Courtesy of Workman Publishing Co.

A perennial expat favorite. Courtesy of Workman Publishing Co.New kids on the block

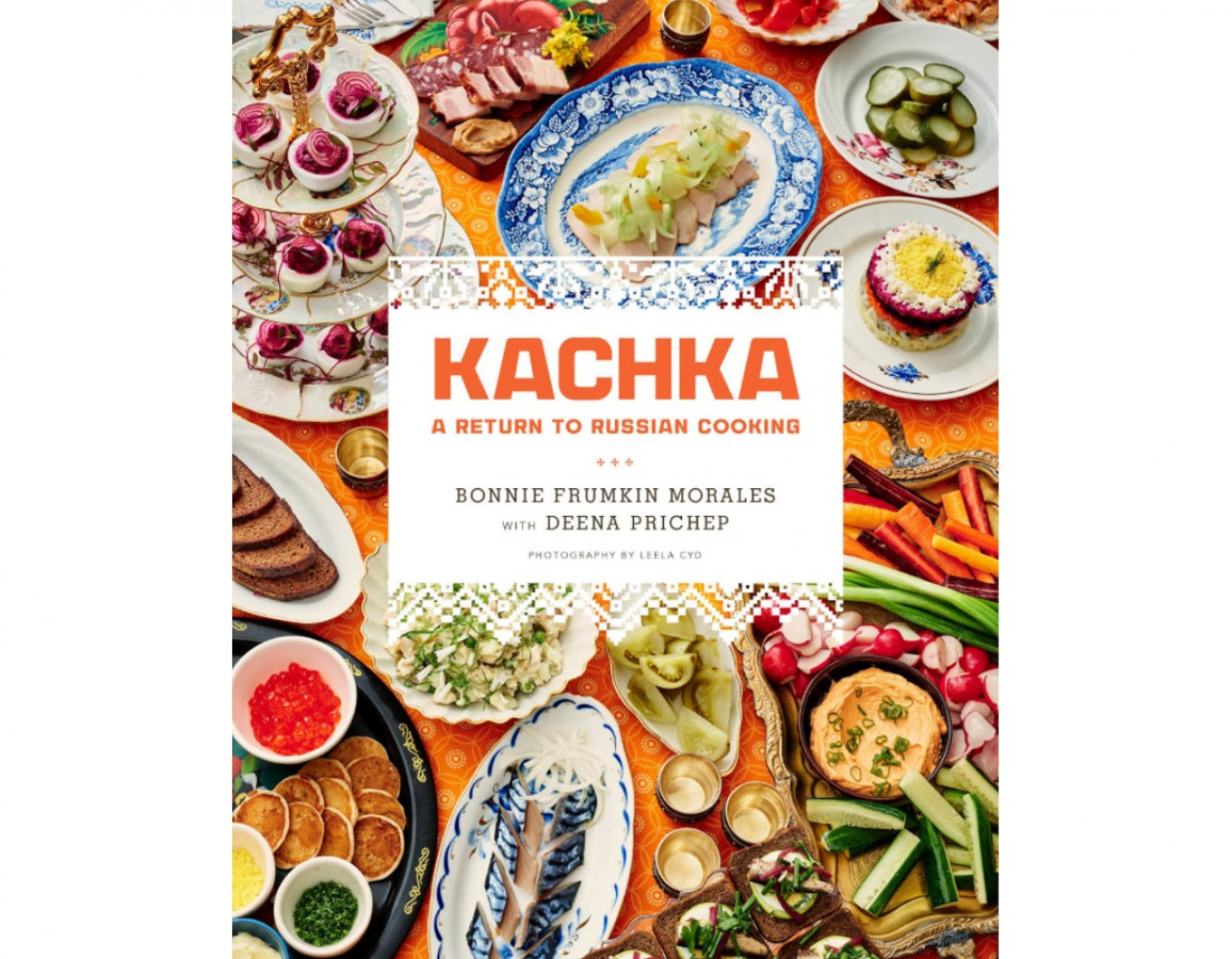

Kachka: A Return to Russian Cooking by Bonnie Frumkin Morales and Deena Prichep (Flatiron Books, 2017)

If Bonnie Frumkin Morales, owner of Portland’s now legendary Kachka restaurant doesn’t have you at her description of a zakuska menu, “How to Tetris your Table,” then you just don’t get either Russian food or humor. “Kachka” is Russian cuisine re-engineered for the Instagram generation, and how well it succeeds! Morales’s breezy, casual yet encouraging style will have your apron on, and your Kitchen Aid mixer fired up and ready to go before you even know what you are doing. ”Kachka” is a compendium of the restaurant’s most popular dishes, featuring easy-to-follow recipes, funky infographics on what to stuff into which kind of dough with ideas for menus, an impressive list of cocktails, and pantry staples to impress.

Try: Cabbage Pirog

From a Portland restaurant. Courtesy of Flatiron Books

From a Portland restaurant. Courtesy of Flatiron BooksMamushka: Recipes from Ukraine and Eastern Europe by Olia Hercules (Weldon Owen, 2015)

Olia Hercules will likely be horrified to find herself on a list of Russian cookbooks since she strongly associates herself with Ukraine, but with recipes like solyanka, pelmeni, and pirogi gracing the pages of her debut cookbook, I find it impossible to exclude her in this list. “Mamushka” is a bucolic exploration of Central Russia’s warm and balmy southern regions, including the Caucuses, where fresh vegetables, berries, and fruit are plentiful. Like many post-perestroika chefs, Hercules is not bothered about introducing elements from other cuisines into her own interpretation of traditional dishes, and her experimentation makes them all the more refreshing. With compelling photos and delicious, easy-to-follow recipes, “Mamushka” should take pride of place on any aspiring cook’s shelf.

Try: Tatar Lamb Turnovers (Chebureky)

Southern cooking Courtesy of Weldon Owen

Southern cooking Courtesy of Weldon OwenSalt & Time: Recipes from a Russian Kitchen by Alissa Timoshkina (Mitchell Beazley, 2019)

“Salt & Time” by the Siberian-born Alissa Timoshkina is an evocative exploration of Russian cuisine. It follows the classic cookbook structure, dividing the recipes into starters, soups, mains, pickles, desserts, and drinks, but the recipes are anything but conventional. Timoshkina has fused her native cuisine with some of the more exciting trends of her adopted homeland in England. Her recipes zing with flavor, and her creativity turns set pieces such as blini and smoked salmon into stunningly innovative creations.

Try: Vegan Bigos with Smashed New Potatoes

Fresh out of the printer’s oven Courtesy of Mitchell Beazley

Fresh out of the printer’s oven Courtesy of Mitchell Beazley