Saturation

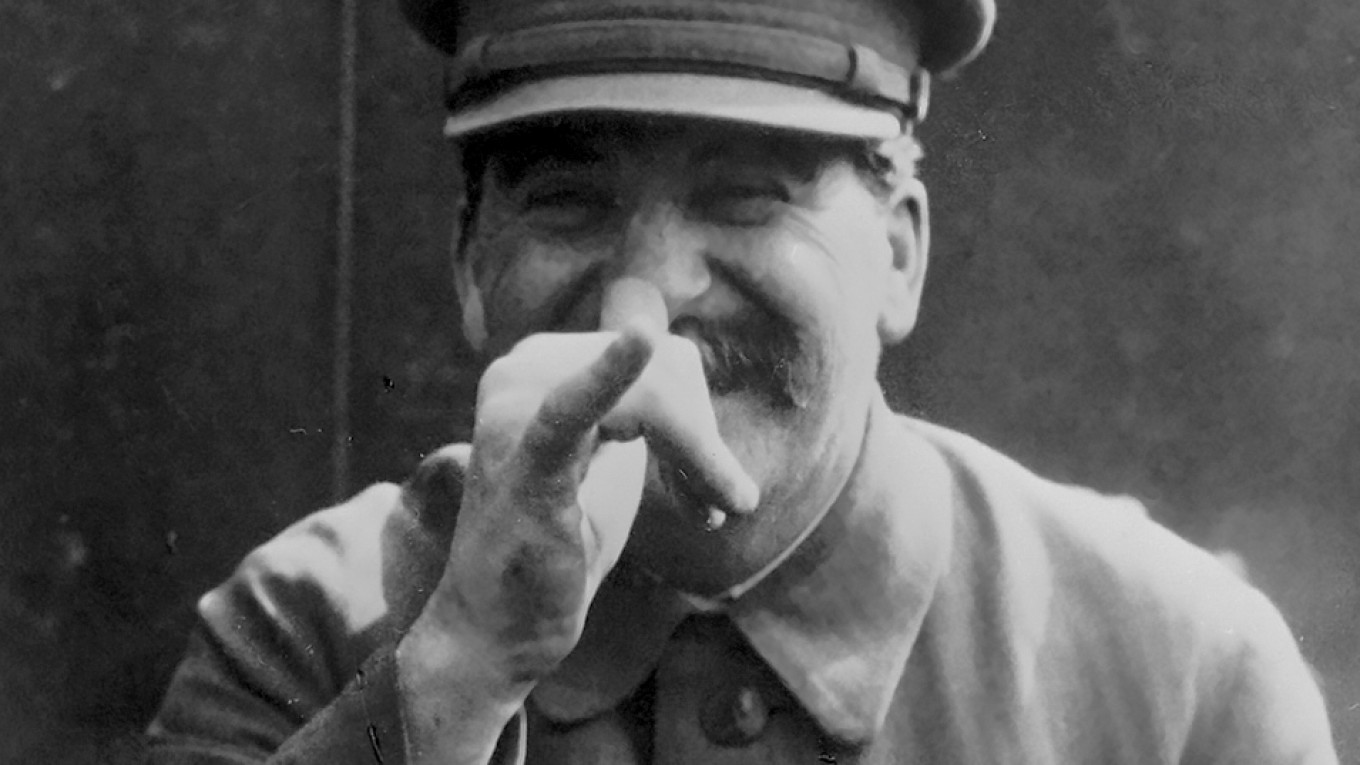

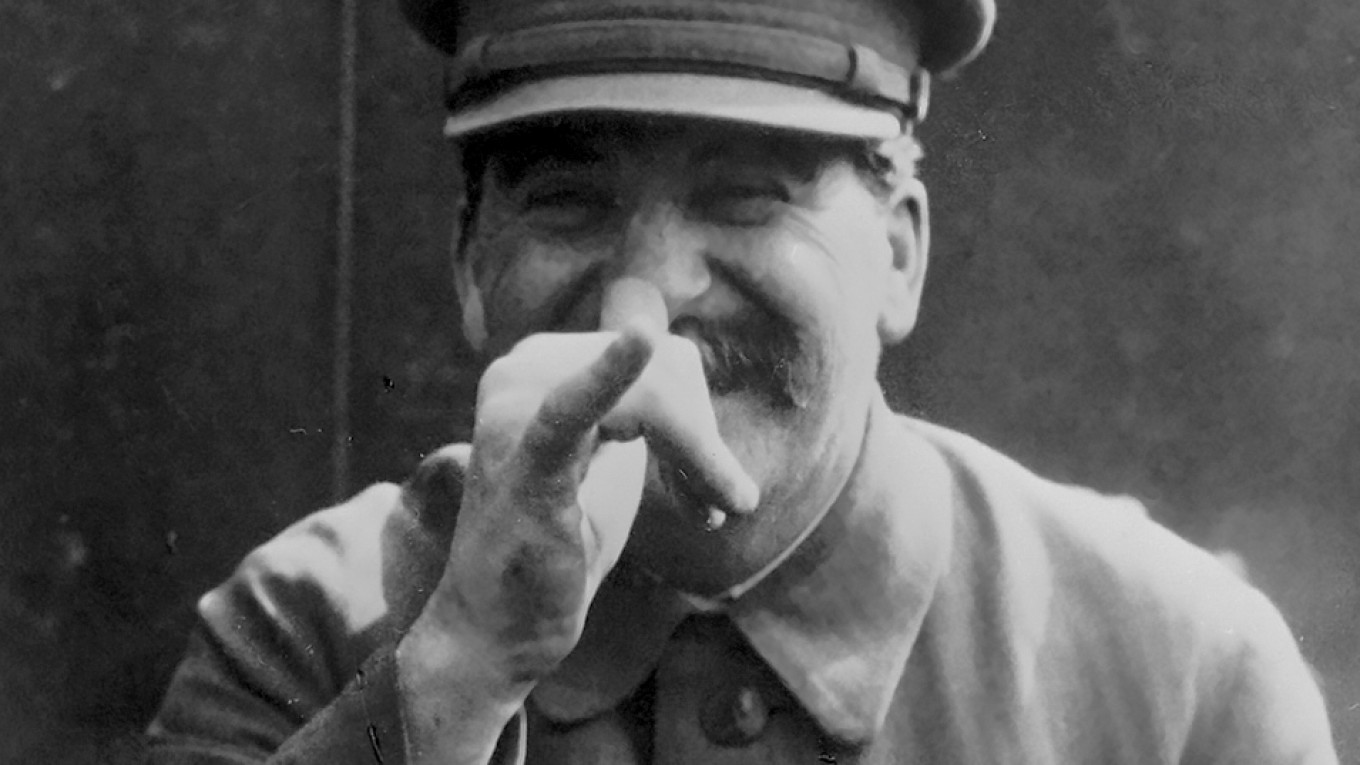

There is no doubt that many Soviet citizens venerated Stalin, but in political humour we can hear many others sharing critical opinions about him and his Cult on a day-to-day basis that rapidly presents us with a very different, more complex image. Let’s consider two anekdoty which turned up numerous times in the archival sources:

Stalin summoned a number of economists and told them he wanted to hold a feast for all the people, a feast so great they would revel (пировать) for weeks. He asked the economists how much this would cost, but no one could say. Then one spoke up and said it could be done very cheaply: ‘Buy a single bullet and shoot yourself – then everyone will celebrate’.

Stalin was out swimming, but he began to drown. A kolkhoznik who was passing by jumped in and saved him. Stalin started to ask the kolkhoznik what he would like as a reward when the latter realised who he had saved. ‘Nothing!’ he said, ‘Just please don’t tell anyone I saved you’.

In each anekdot, the underlying assumption is that the population at large hates Stalin and would prefer him dead. There’s a sense here that Stalin is the principal cause of people’s suffering; as another anekdot had it, rather elliptically, ‘In our country we have such an artist that when he performs, the whole nation weeps’. More directly, a Harvard Project respondent recalled a simple pun, altering Stalin’s propagated role as Leader and Teacher (vozhd’ i uchitel’) to Leader and Torturer (vozhd’ i muchitel’). If Stalin was ultimately to blame for their hardships, then citizens could readily imagine that his death would improve their lives.

As this implies, far from being a taboo subject for mockery, or deemed to sit benignly above politics, Stalin was considered and treated in humour as Public Enemy Number One: he was the default object of popular sarcasm, mockery and criticism, and was targeted more often than any other leading figure. As a later Romanian joke described their own dictator’s, Ceauşescu’s, cult, ‘In laughter as in life, he is at the center’.

In fact, the very saturation of the Stalin Cult became a subject of mockery in its own right. A letter sent to Andrei Zhdanov (Kirov’s successor as Leningrad Party boss) makes this point in subtly absurdist fashion, detailing in a long list the ubiquity of Stalin’s name by the later 1930s:

Dear comrade Zhdanov!

Do you not think that comrade Stalin’s name has begun to be very much abused? For example:

Stalin’s people’s commissar

Stalin’s falcon

Stalin’s pupil

Stalin’s canal

Stalin’s route

Stalin’s pole [sic]

Stalin’s harvest

Stalin’s stint

Stalin’s five-year plan

Stalin’s construction

Stalin’s block of communists and non-party members

Stalin’s Komsomol (it’s already being called this)

I could give a hundred other examples, even of little meaning. Everything is Stalin, Stalin, Stalin.

Although this author went on to encode his message as constructive advice to the leadership, actually warning them of the risk of absurdity such a prevalence of Stalin’s name engendered, many others seized on this absurdity directly. For example, a lawyer recalled that, in his workplace in Odesa, on the sign for the toilets someone appended the words ‘named after Stalin’ (туалет им. Сталина). Less overtly, some Komsomol members in Bashkirskaia oblast’ amused themselves by renaming their canteen’s dull cabbage broth ‘Stalin soup’ – an appellation that could sit quite happily alongside the others on the list sent to Zhdanov.

This vein of sarcasm as a response to the overbearing nature of the Cult is neatly summed up in an anekdot which recounts how, for an anniversary celebration of Tchaikovsky’s work, there was ‘a two-hour speech about Comrade Stalin and nothing said at all about Tchaikovsky’. A similar joke described how the centenary of Pushkin’s death (1837) would be marked with the erection of a statue which, via several planning revisions, becomes a colossal statue of Stalin holding a small volume of Pushkin’s poetry.

More significantly, rather than just mocking the Cult’s excesses, by inverting the practice of associating Stalin with every element of life or official policy, he could easily be blamed for everything. When the abolition of student grants was announced in October 1940, M.V. Pen’kov blamed Stalin directly, yelling a parody of an official slogan back at the radio announcement in a room of his contemporaries: ‘Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for [this] happy life!’ Similarly, in Saratov, an unnamed girl was sentenced to five years for being late to work, to which she responded with withering sarcasm, ‘Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for a happy childhood’, mocking another famous slogan. And, in mid-1940 when the working day was increased from seven to eight hours, Lashina, an accountant in the Northwest shipping fleet, ranted angrily to her colleagues, concluding, in tones of withering scorn, ‘Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for stretching out your hand to us, although we have already stretched out our legs,’ melding a propagandistic image of Stalin the paternal teacher with a colloquialism meaning ‘to kick the bucket’. She was not the only one to respond this way: V.A. Marandzheev, the chief of staff at a musical instrument factory, interjected during a radio broadcast of a lullaby praising Stalin, maintaining the high register of the song for comic effect, ‘Hallowed be thy name, Stalin. The workers offered unto Stalin the sacrifice of their 6- and 7-hour working days’.

How can these anekdoty and biting one-liners fit with the generally accepted ideas about the Stalin Cult and its importance? Was its influence over people’s understanding of and engagements with the regime much less than has so long been claimed? In fact, that Stalin was so often the principal target of mockery doesn’t mean that his Cult of Personality was unimportant or unreal. On the contrary, that he so frequently featured in critical humour actually demonstrates how closely he was associated with the regime in the minds of the people. But being the symbol and centre of both the Party and the Soviet Union wasn’t always a good thing to be when criticism and discontent demanded a ready target.

What it does suggest, however, is that although (as countless historians have argued) the Cult’s significance grew disproportionately over the course of the 1930s, many citizens responded to it much as they did to any other official state policy. That is, they received and judged it selectively and critically; it was neither embraced wholesale, nor was it simply dismissed out of hand. Responses depended on changing events, specific policies, and personal experiences. It is in any case rather unrealistic for us to expect to find a static or even a singular opinion of Stalin, even in the mind of a particular individual; people are simply too complex and contradictory for that. Yet when we ask questions about ‘popular opinion’ we usually want to find a nice, clear answer rather than a mixed one, which is precisely what makes a continuing emphasis on the explanatory power of the Stalin Cult so appealing. But the Stalin Cult cannot simply ‘explain’ popular opinion to us, even if contemporaries frequently and pointedly used it to help explain their difficult lives to themselves.

Note: For ease of reading, the footnotes have been removed from this section.

Excerpted from “It’s Only a Joke, Comrade.” Copyright © 2018 by Jonathon Waterlow. Used by permission. All rights reserved.