For centuries people all over the world have made jam to preserve the harvest. We don’t know when exactly it appeared in the Russian kitchen, but we do know that the ancient recipe for jam is very different from the one we use today. And the big question is: Would we have liked it?

In Russian, the term for jam is варенье, which just means “something boiled.” It only came to mean something sweet in the 17th and 18th centuries. Until then, “jam” was just used in the sense making something through boiling, such as salt or ink. There was even “silk jam”: boiled silkworm cocoons. It appears that people made sweet jam in Russia in previous centuries, but it didn’t have a special name. For example, “cherries boiled in honey” might have been like our jam even if it was called something else.

So, what is classic Russian jam? It is berries or fruit boiled in syrup. The fruit and berries can be whole or cut into pieces. But jam could be made of other products, too. Ancient Russians made jams of ginger in honey, radishes in molasses, nuts in honey, and so on. Molasses in ancient times was thin, clarified honey. The dishes made with it are mentioned in “Domostroi” (1550s): “Lingonberry water and cherries in molasses, and raspberry punch and all kinds of sweets, and apples and pears in kvass and in molasses.”

As you can see, jam — although it was not called that back then — was a dish that wasn’t exactly inexpensive, but it was fairly common. In “Domostroi” it is described being served in affluent homes, but it also appeared on the royal table. In fact, the richer the table, the more sophisticated the jam. Here is an example from the menu of Empress Anna Ioannovna (1730s): “Treats at court festivities were always abundant, although quite monotonous. Among the sweets were jellies, ice cream, candies, suikerbrood, various jams, fruit marshmallows, and soft jelly candies.” Even the person compiling this list did not bother to specify what kind of jams were served; there were too many to describe.

The menu during the rule of Anna Leopoldovna (1741) included such sweets as apple marshmallows, plum jellies, ginger in molasses, berry jelly, and jams made from Seville oranges, pears, plums, cherries, gooseberries, barberries and currants.

In the 17th century cane sugar was imported into Russia, but it wasn’t immediately used throughout the country — naturally, it was quite expensive. In ordinary homes, honey was used more often. Water was sweetened with honey or berry juice to make fruity drinks. Molasses (thin, clarified honey) was used for preserving berries and fruits. In “Russian Cookery” (1795) Vasily Lyovshin describes in detail how to make it. “Choose the best honey,” he writes, “and clarify it like this: put it in bowl on a trivet [on the fire]. When it comes to a boil, carefully skim off the foam. You can tell if it is ready this way: put a hen’s egg in it. If it sinks, it means that it is not ready. If it floats on the surface, take it off the fire. You can cook a variety of berries and fruits in this honey.”

Once you have the thinned, clarified honey, making jam was easy. Lyovshin wrote that cooks should “boil cherries as much as possible, stirring frequently and removing the foam,” and “boil until the syrup permeates the apples, skim the foam and stir constantly so it does not burn.” Even cucumbers could be made into jam. It was recommended to “cut them in half and seed them, boil them in honey, flavoring with ginger and a lot of pepper.”

Over time sugar gradually became more and more accessible. In St. Petersburg in 1719 the merchant Pavel Vestov opened a factory to process sugar cane. And in 1721 Peter the Great issued a decree “On the prohibition of sugar imports into Russia,” after which the authorities simply limited the import duty to 15%.

But sugar was still not cheap. All the same, jam made with sugar is already mentioned in Nikolai Yatsenkov’s “Newest Cookbook” published in 1790-91. Although it is mostly a translation from the French original, the demand for these tips among the Russian public clearly shows that sugar was no longer just a tsarist amusement. But still, the quality of the product back then was far from what it is today. Lumps of sugar had to be boiled, foam skimmed off the top to clarify it (like honey). Then it could be made into a syrup.

It is interesting that one of the volumes Yatsenkov’s edition, called “Malorssian Confectionary Book,” is no longer a translation but a collection of recipes by the author from “notes up to and concerning jam.” Here, too, sugar was widely used, which clearly speaks of its prevalence and availability. “Pour grated sugar into a pan, lay on top little rows of good raspberries, cook them a bit, add two spoons of water, and then put them up in a jar with syrup.”

The emergence of Russia’s own production of beet sugar sharply reduced the cost of making sweets. The first experiments with beet sugar were made in Russia in the early 1800s by Major-General Georg (Egor) Blankenagel, a native of Livonia. The Patriotic War interrupted his work, and this new type of sugar was only produced in Russia starting in the 1820s. By 1840 there were already 164 sugar factories in the country making sugar from beets.

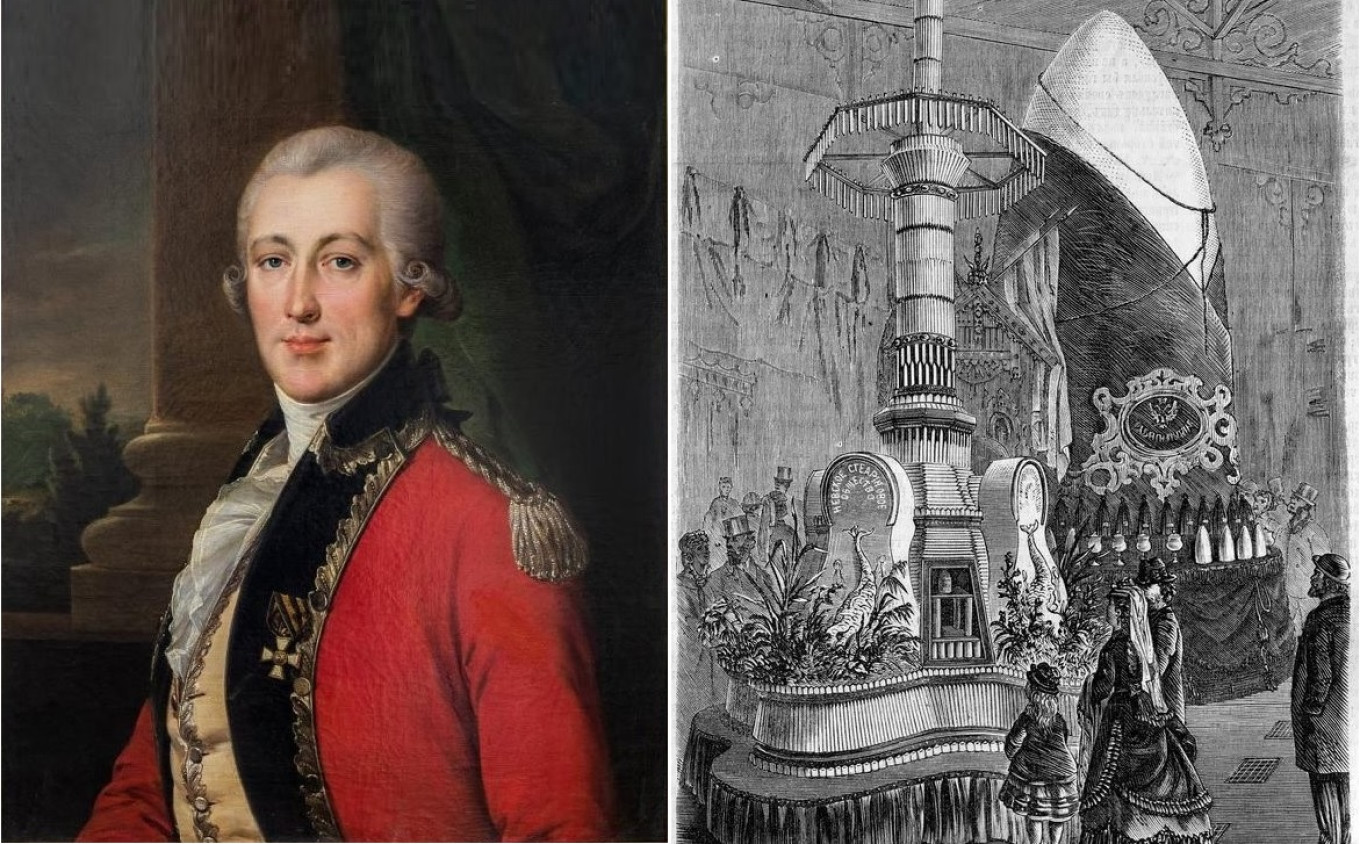

Below: Georg von Blanckennagel (unknown artist, late 18th century) and a giant head made of sugar at the manufactory exhibition of 1870 in St. Petersburg (Journal “World Illustration”).

But for many years jam was made with both honey and sugar. The poet Alexander Pushkin seems to have liked both. The memoirist and maid of honor of the court, Alexandra Smirnova-Rosset, wrote that the poet’s favorite was white gooseberry jam, made with a pound of berries, two pounds of sugar and one cup of water. But in “The Captain’s Daughter” Pushkin mentions another treat sweetened with honey: “Once in the fall, my mother cooked honey jam in the fireplace of the withdrawing room as I stared at the boiling foam and licked my lips.”

In classic jam, the trick is to keep the berries or pieces of fruit from breaking up. To keep the pieces whole, jam is cooked in several steps. If the berries are juicy (raspberries, strawberries, cherries, or black currants), they are picked over and washed, covered with sugar, and left for 3-4 hours until the berries release their juice. Then they are brought to a boil and left to cool for 5-6 hours. Then the jam is boiled a second time for 10 minutes, after which it is again left to cool for 5-6 hours. Finally, it is brought to a boil for just 3 minutes and immediately poured, hot, into sterile jars.

But there is also a quick trick to make jam: cover berries in sugar, leave for 3-4 hours until they release their juice, then cook in one step until ready — check the temperature and see if the syrup has thickened. After the jam is ready, it is poured into sterilized, dry, hot jars. Be sure they are bone dry: moisture can lead to mold and fermentation.

Five-Minute Raspberry Jam

Ingredients

- 1 kg (2.2 lb) raspberries

- 1 kg (2.2 lb) sugar

Instructions

- If the berries are clean and unmarred, it is best not to wash them. Remove the sepals (the part that connects the berry with the stalk) and stalks.

- Cover the raspberries with sugar and leave for 3-5 hours until juice appears.

- Put the raspberries in a pan on the stove, bring to a boil, stirring gently.

- Boil for 5 minutes, immediately pour into sterile jars and cover with lids. Store in a cool place.