In its 874-year history, Moscow has grown from an obscure twelfth-century military outpost into a world-class capital city of over 20 million inhabitants. Along the way, the city has been reinvented over and over to suit the needs of its rulers. Ivan the Great made Moscow “The Third Rome” after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, raising stone cathedrals inside the Kremlin whose golden domes still characterize the city’s skyline. Peter the Great relegated Moscow to second-city status when he transferred the capital to his newly minted St. Petersburg, and in doing so, made Moscow a center of conservative thought and Orthodox belief: Moscow’s famed forty-times-forty churches soared above the city’s two and three-storied secular edifices.

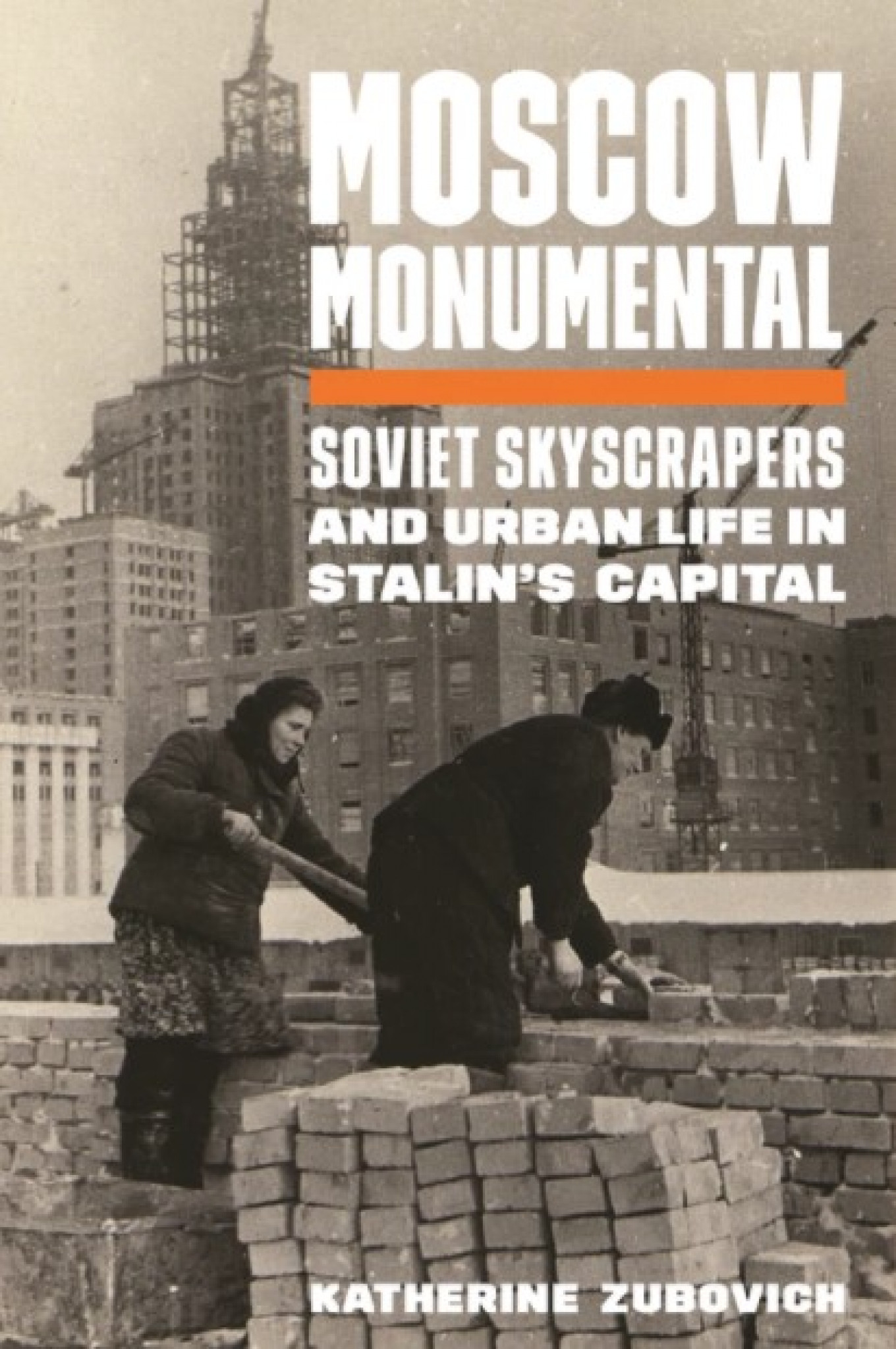

When Vladimir Lenin moved the capital of his nascent Bolshevik state back to Moscow, he overtly turned his back on St. Petersburg’s imperial legacy while also recognizing that it would take a Herculean effort to turn Moscow into the global capital of the new communist world. The story of that effort is the subject of Katherine Zubovich’s new book “Moscow Monumental: Soviet Skyscrapers and Urban Life in Stalin’s Capital.”

Professor Zubovich brings mastery of Russian and Soviet history together with an extensive understanding of art history to tell the engrossing story of how Moscow’s modern skyline took shape in the turbulent 20th century. In an engaging style that draws on diaries, memoirs, letters, and meeting minutes, Zubovich first chronicles the government’s ambitious plans to construct a massive Palace of Soviets on the spot where the new Christ the Savior Cathedral stands today. This is a challenging task as the former monumental edifice was never built, but Zubovich brings to life the evolving plans for this centerpiece of the new Moscow ensemble, including pre-war efforts to involve Western architects and engineers to facilitate the construction of something utterly foreign to Russian architecture: the skyscraper.

Moscow’s skyline today is dominated by the seven Stalin-era “vysotniye” or “tall buildings,” which were originally planned as satellites around the central Palace of Soviets. These buildings — often known among foreigners as “Stalin’s wedding cakes” — ultimately were built, and to this day serve their original purpose: two are ministries, two are hotels, two are residential buildings, and the largest is the central building of Moscow State University. At first glance — or even after several decades — the seven may seem identical, but “Moscow Monumental” recounts that they are anything but. The stories of their planning and eventual construction spans the decades before and after World War II and features some of the most famous names in Soviet History.

But it is lesser-known personalities who come to brilliant life in “Moscow Monumental” in stories of those who built the skyscrapers and of those whose lives that were disrupted by their construction. It is this aspect of “Moscow Monumental” that gives the book such universal appeal: Zubovich has done stellar work in the city’s archives, uncovering a trove of letters and petitions from ordinary Soviet citizens, who ask for help in relocation as their homes are demolished to make way for the new buildings, or who make their case for the right to occupy an apartment in the new houses. This central tension between the Muscovites who are moving “up” the new Soviet hierarchy and possibly into the upper floors of the buildings on Barrikadnaya or Kotelnicheskaya and those who are moving “out” to the inelegant and barely cobbled together new suburbs makes “Moscow Monumental” far more than a study in urban planning. This is a book which delves into the very human tensions created by a society forced into transition, and the effects on a city undergoing a seismic political, cultural, and architectural change.

Excerpt from Chapter 6 of “Moscow Monumental”

The Vysotniki

The young welder E. Martynov would never forget his first day of work on the university construction site. Winding his way through small mountains of freshly dug dirt, Martynov glanced up at the metal columns that had recently been planted into the ground below and now stretched far up into the sky. It was a clear spring day and Martynov could feel the air around him vibrating from the clanging, clattering, screeching sound of the machines that were hard at work nearby. Martynov handed his documents to comrade Fedorov, a Stalin-award-winning foreman, who carefully looked over the papers, sizing up the young man with a sideways glance before giving him an easy task to start. Martynov would later admit that he was a little nervous on that first day. This was not just any construction site, after all. This was the future site of the 32-story Moscow State University (MGU), a building known at the time as the “Palace of Science.” And those who worked on this building were not just ordinary construction workers; they were “vysotniki.”

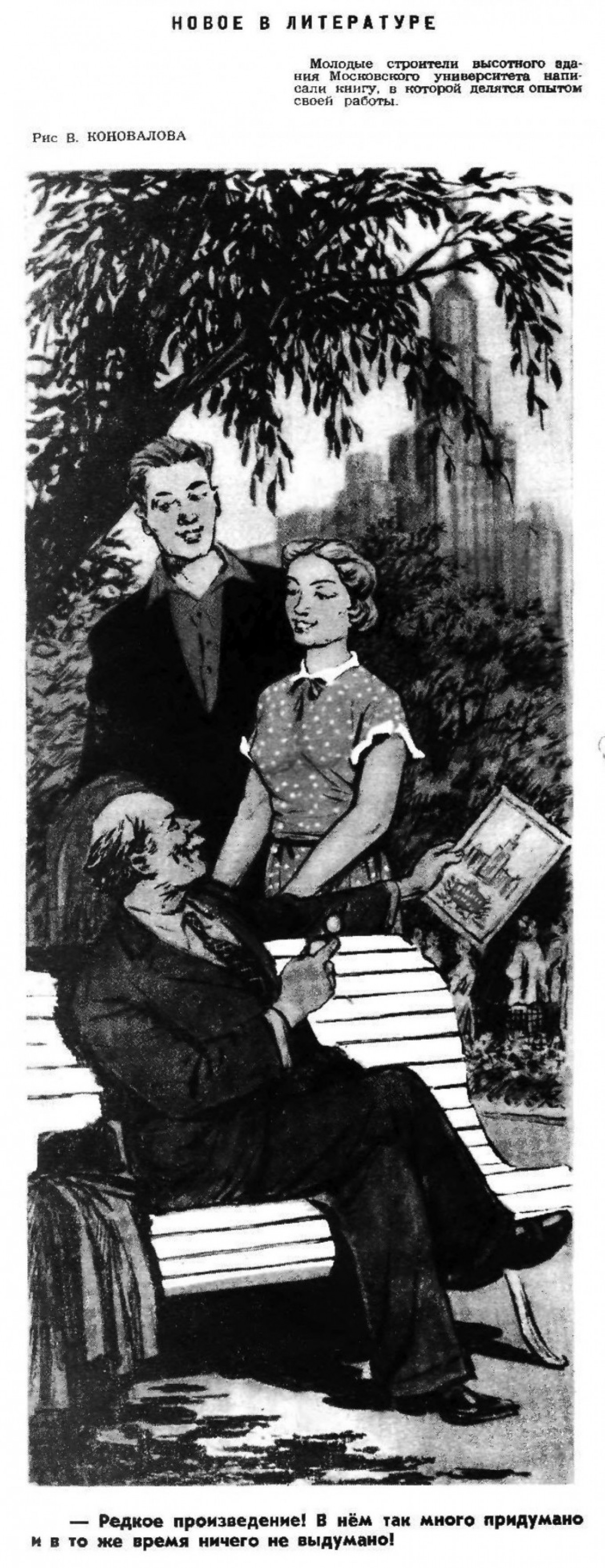

Martynov’s account of life on the MGU construction site is, of course, an idealized one. It was published in 1952 in a special collection of narratives written by workers, foremen, and architects printed by the Soviet trade union press one year before the new university building opened its doors to the first cohort of students. There was a ready audience both in Moscow and beyond for the fifteen thousand copies of this booklet that celebrated the achievements of the builders of MGU. The Soviet satirical magazine Krokodil highlighted the publication of the booklet in its August 1952 issue, announcing to its readers that “the young workers of the tall building of the Moscow university have written a book that shares the experiences of their work.” In the accompanying cartoon image, an older reader seated on a park bench holds a copy of the book in his left hand (fig. 6.1). Glancing up at two healthy young workers, the old man congratulates them: “A rare piece of work!” he exclaims. “In it, they come up with so much yet at the same time don’t make anything up!”

The publication and celebration of narratives like Martynov’s in 1952 was part of a larger project to make popular heroes out of Moscow’s skyscraper construction workers. This chapter examines these heroic narratives and the ideological work they did in the postwar Stalin era, but it also considers the silences and absences in such texts. Accounts of the mismanagement, faulty work, accidents, and reprimands that were a part of daily life on the construction site are not printed in that 1952 booklet. The real difficulties of carrying out such monumental construction projects are acknowledged in Stalin-era workers’ narratives, but these texts aim to convey to the reader how challenges were overcome, usually in stories about workers banding together to succeed against all odds. Published narratives about the university’s construction repeated a familiar set of literary conventions established across decades of socialist realist works.

Also not printed alongside Martynov’s account are the experiences of Gulag workers and former Gulag inmates whose sentences had been reduced in exchange for their work building up postwar Moscow. Like Martynov, Ismail G. Sadarov worked on the university skyscraper project, though he did not freely wander onto the construction site to report for his first day of work. Sentenced in 1947 in the North Ossetian ASSR to seven years imprisonment for military desertion, Sadarov was given early release in 1950 in exchange for working on the construction of Moscow State University. Sadarov’s experience building the university skyscraper survives in a slim historical record that is a faint whisper when held up against Martynov’s much louder voice. And yet, these men, along with thousands of other men and women like them, inhabited the same small world of the university construction site. Weaving together their voices is the goal of this chapter, which examines how the vysotniki were idealized in Soviet popular culture and how they lived and worked in reality.

Builders As Heroes

The word “vysotnik” is derived from the Russian word “vysota,” or “height”; it was a term applied to all construction workers engaged in building Moscow’s skyscrapers. They included in their ranks both skilled and unskilled laborers and as a group were counted among the heroes of the postwar era. Each of Moscow’s eight skyscraper construction sites employed a variety of vysotniki, from those who worked at the top of the structures to those working closer to the ground, digging foundation pits and fixing in place the metal matrices needed to reinforce concrete. But as the nickname implies, “vysotniki” were best known and most celebrated for their work scaling the tall buildings. From the early 1950s, these men and women could be seen climbing up the tall metal carcasses of Moscow’s enormous new structures to carry out their work as welders, granite workers, stuccoists, and steeplejacks (verkholazy). Craftsmen like E. Martynov secured, sculpted, and shaped the spires of Moscow’s skyscrapers (fig. 6.2). And in the process, they were some of the first to see Moscow from the new vantage points created by the city’s tall buildings.

Whether gazing out across the city from the outlying tower on the Lenin Hills or from the more central spire on Smolensk Square, the vysotniki saw Moscow in an entirely new way. This fact was often used as the basis of metaphor in vysotnik narratives, like Martynov’s published account from 1952, which culminates with the young worker triumphantly gazing out across the cityscape from just beneath the newly-installed gold star atop the university skyscraper. “The fog faded away, and all of Moscow became clearly visible,” Martynov wrote. From the top of the building, Martynov could see that “the Soviet people are building their own beautiful future! They are dreaming not of war, but of peaceful, happy lives!” A keen observer not just of the built environment but of Soviet society as a whole, the figure of the vysotnik was endowed with special powers of perception. From his or her unique vantage point, the skyscraper builder was able to assess the state of affairs below. Not all vysotniki, of course, would see the world through the optimistic eyes of the young Martynov.

Moscow’s vysotniki of the late Stalin era were idealized and celebrated in popular culture in the mold of Soviet heroes before them. The term “vysotnik” had an earlier usage that ensured that Moscow’s skyscraper builders were closely associated with the heroic. In the 1930s, it was in most cases used to refer to Soviet aviators (letchiki-vysotniki). In the Soviet Union, as in the United States, the interwar period was the age of great aviator-explorers. In the Soviet case, the aviators of the thirties conquered the popular imagination with their daring flights to the arctic. (In 1937, against the backdrop of the purges, Soviet aviators first landed an aircraft at the North Pole and then broke the world record in long-distance flying by traveling over the arctic from Moscow to the United States.) From 1941, aviator-vysotniki featured as key figures of the Soviet war effort. But by the late 1940s, the word “vysotnik” had come to refer, in Moscow at least, mainly to the workers involved in skyscraper construction.

Like the aviators before them, these builders captured popular attention by reaching for new heights. That aviators and skyscraper builders were so closely linked in the Soviet imagination is not surprising, given the symbolism attached to their respective achievements. Their shared goal of reaching for new heights—whether by plane or by skyscraper—was rooted in the same inclination. This was not a uniquely Soviet phenomenon. As Adnan Morshed writes, in the early- to mid-twentieth century “the skyscraper was popularly seen in the role of the airplane’s urban alter ego.” In both airplane manufacturing and skyscraper building, planners combined technology with human force and bravery to create spectacles in the sky. Airplanes and skyscrapers alike were at once beautiful and sublime, awe-inspiring and terrifying.

Those who built these structures could be similarly described. In New York City in the 1930s, newspapers tracked the construction of the Empire State Building day by day in serialized accounts of the brave workforce of the city’s “sky boys” and “poet builders.” These men, immortalized in the photographs of Lewis Hine, were as diverse in ethnic origin as their Soviet counterparts were two decades later. And any New Yorker who found themselves in Moscow after the war would have been reminded when hearing stories about the vysotniki of similar narratives from the interwar years back home. The Soviet Union was nonetheless keen to emphasize the differences between its monumental building projects and skyscrapers built abroad. While one group of skyscraper workers built in the name of capitalist “progress,” the other labored in the pursuit of “communism.” But perhaps the key difference was that the vysotniki understood their work as an extension of wartime sacrifice.

![Figure 6.3: “My father defended Stalingrad, and I am building [it back] up” / “Moi otets otstaival Stalingrad, a ia otstraivaiu.” Krokodil, May 20, 1953. Courtesy of "Moscow Monumental"](/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/katherine-zubovichs-magnificent-moscow-monumental-3.jpg)

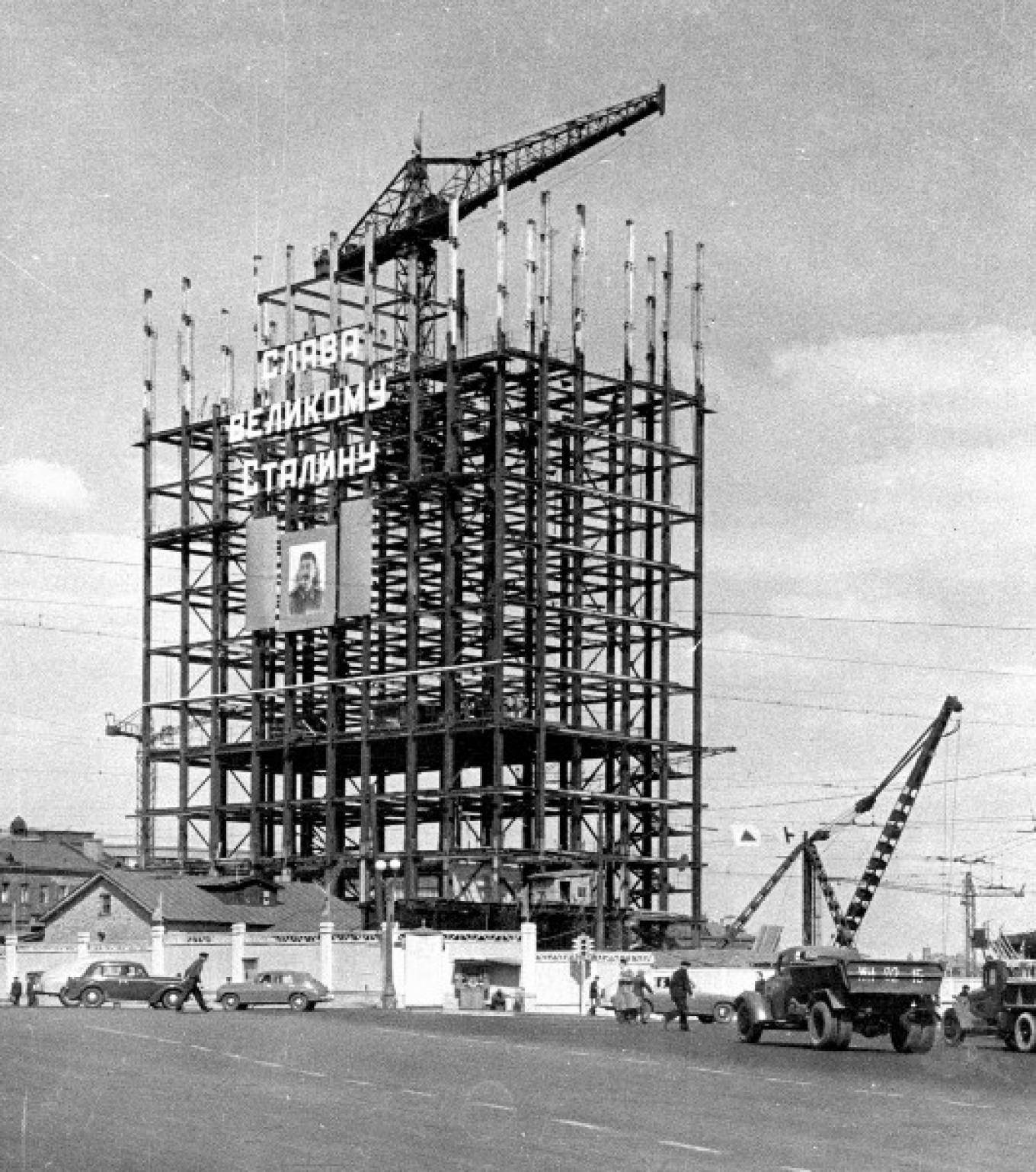

Moscow’s vysotniki were swiftly incorporated in the late 1940s into the pantheon of Soviet revolutionary and wartime heroes. Construction workers were important figures in the Soviet imagination in the 1930s, but the immense tasks of postwar reconstruction served to move this category of worker to center stage. Soviet writers and officials worked to forge strong associative links between postwar building and wartime heroism. As the construction worker pictured on the May 1953 cover of Krokodil put it, “My father defended Stalingrad, and I am building [it back] up” (fig. 6.3). Many of Moscow’s young vysotniki had similar stories about their fathers’ and mothers’ heroism, and many more had fought in the war themselves. These wartime experiences remained relevant in the work being done on the construction site, where large banners were hung from the steel carcasses of the buildings with war-related and patriotic slogans, including “In peaceful days” (V mirnye dni) and “Glory to Comrade Stalin” (fig. 6.4). Fedor Lagutin, a master concrete worker on the university construction site, recalled in 1952 that nine years earlier he had been stationed with his battalion far from Moscow, on the Rybachii Peninsula up north. Knowing that Lagutin had worked before the war in the capital city, the other soldiers in the battalion, none of whom had ever been to Moscow, asked Lagutin to describe it. “I began talking about the Kremlin,” Lagutin recalled, “about the wonderful stations of the metro, about the wide and spacious streets and squares, and the new beautiful buildings.” But Lagutin’s description of Moscow was quickly cut short as German artillery began to shell the unit. “Everyone rushed to their positions …” he recalled. Then, “when the enemy guns fell silent, one of the soldiers piped up: ‘Just you wait,” he exclaimed, “we’ll finish fighting this war, and then we’ll build such palaces that you will sigh in amazement.’ ” For Lagutin, whose leg was amputated during the war, the university skyscraper on the Lenin Hills was one of these palaces. After the war, Lagutin was determined to continue working in construction, despite the challenges presented by his disability. “I will build again!” Lagutin told himself. If the Soviet flying ace Alexei Mares’ev could get back up into the sky with two prosthetic legs, so could Lagutin, the concrete master resolved. In 1949, Lagutin was put in charge of the concrete division at the building site of Moscow State University.

Older workers like Lagutin tied personal frontline memories to the construction site, but for the younger Martynov, it was the act of bearing witness to wartime destruction on the home front that spurred him on in his work. Still a child when the war began, Martynov remembered the year 1941, when his father left for the front and his mother started work at a factory. The family had moved just a few years before to the outskirts of Moscow. They settled in a little house with a small yard next to the construction site of a new school. As a child, Martynov would wander out of his yard and onto the construction site next door to watch the builders at their work; sometimes the workers would allow the boy to help out by holding bricks and tools. Each day Martynov would return home covered in dirt until the school was finally finished and the boy was old enough to enroll. When the school was destroyed in that first winter of the war by the Germans, Martynov was crushed. “She was demolished by the bombs that were thrown down and tore through the outskirts of Moscow by fascist pilots,” Martynov recalled in 1952. “Tears welled up in my eyes,” he continued, “at the sight of the mound of broken bricks.” A few months later, Martynov joined the ranks of the city’s construction workers, training to mend his broken city by becoming a welder. A decade later he would pay homage to his lost school by helping to build the country’s premier university.

Soviet skyscrapers served as a means through which both the state and the self could be rebuilt after the war. It was often the able-bodied male builder who featured on magazine covers and in published texts. But, as even the most idealized vysotnik narratives attest, the skyscraper construction sites were filled with the scarred bodies of shell-shocked warriors who had lost far more than limbs in the recent war. Wartime trauma runs throughout the construction worker narratives printed alongside Lagutin’s and Martynov’s in that small booklet of 1952. While Moscow’s skyscrapers stood as monuments to Soviet victory in the war, their construction also served as the means through which builders could overcome past grief and loss. Those wishing to take up the metaphor might make themselves whole again through work, rebuilding the self along with the city. Soviet production novels of the twenties and thirties could serve as the model for a vysotnik wishing to reforge himself on the construction site. Only instead of returning home after the Civil War to rebuild a cement factory, like Gleb Chumalov in the novel Cement, decorated veterans now returned from the Great Patriotic War to build skyscrapers in Moscow. As Ogonek magazine put it in 1952, “before our eyes Moscow is transforming, enormous bright buildings are climbing up to the sky, and alongside Moscow, together with her buildings ordinary Soviet people grow—the rank and file builders of communism.”

For ease of reading, footnotes have been removed from this excerpt.

Excerpted from “Moscow Monumental: Soviet Skyscrapers and Urban Life in Stalin’s Capital,” by Katherine Zubovich. Copyright © 2021 Princeton University Press. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Katherine Zubovich is an assistant professor of history at the University of Buffalo, State University of New York. She is also working on a short book, “Making Cities Socialist” to be published as part of the Cambridge Elements in Global Urban History series. Follow her on Twitter at @kzubovich.

For more information about Katherine Zubovich and her books, see the publisher’s site here.