An economist by education, Ksenia Buksha has worked in finance, marketing, and advertising. She is a mother of three, plays the guitar, draws, and paints. She is also, writer Dmitry Bykov asserts, one of the best poets of her generation, although she is better known for her prose. The 37-year-old St. Petersburg native has published numerous novels, short story collections, a poetry collection, a guidebook on business reputation management, as well as a biography of the Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich.

Buksha’s writing—brisk, yet richly atmospheric, and often punctuated by her own abstract paintings and drawings—explores love, youth, orphan-hood, death, and everyday life in all of its uncanny drabness. Often set in St. Petersburg, many of her novels interweave seemingly unconnected characters into a single topography of the city. Her latest novel, “Churov and Churbanov” (2019), is a thriller in which two former schoolmates—one a pediatric cardiologist, the other an errant entrepreneur—are connected by a single heartbeat. Her 2018 collection of stories, “Opens Inward,” follows a transport route stretching from one end of her own Petersburg region to the other while interlocking its denizens in a poignant triptych of birth (“Orphanage”), life (“The Asylum”), and death (“Last Stop”).

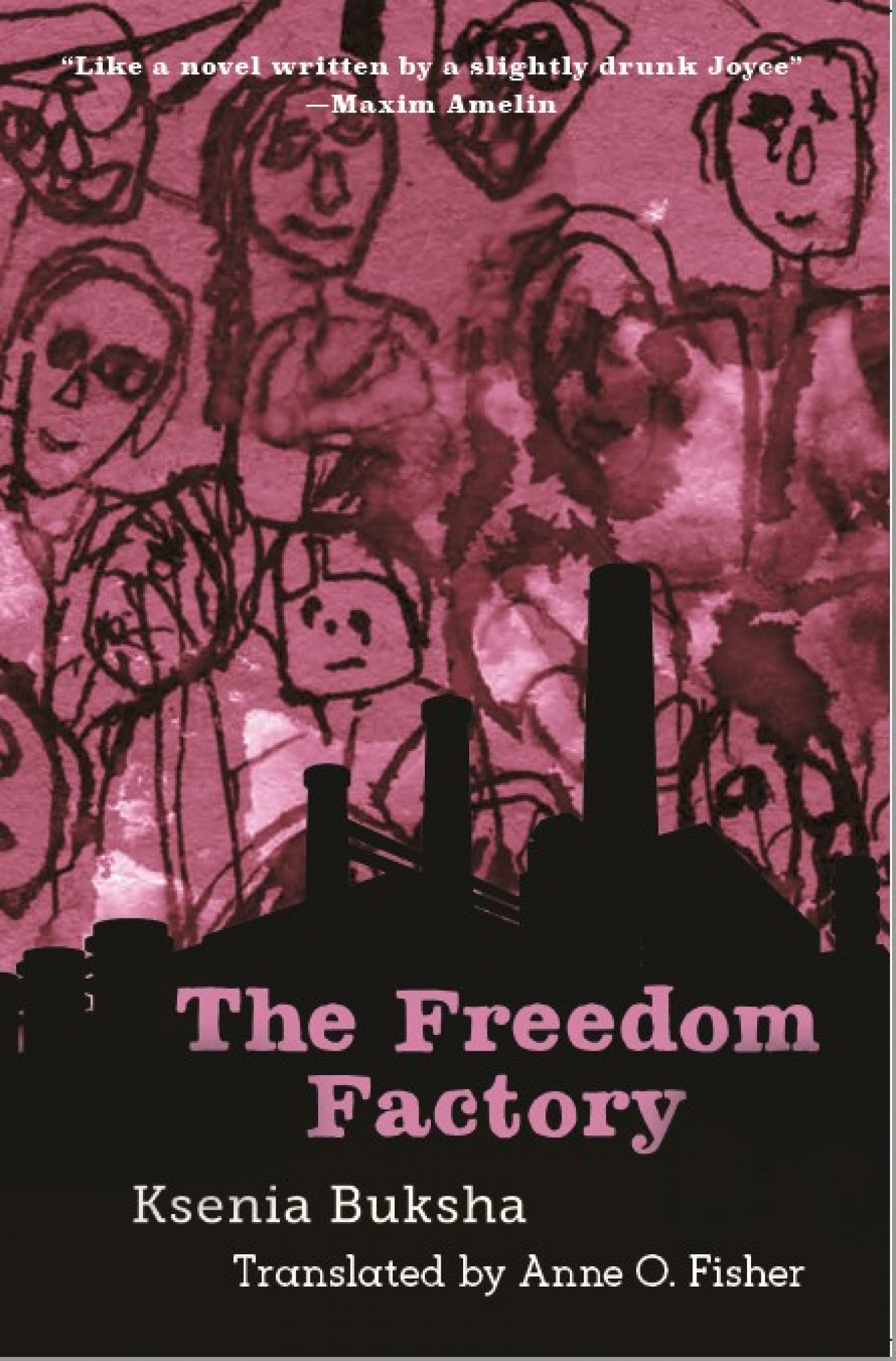

“The Freedom Factory,” translated by Anne O. Fisher (Phoneme Media, 2018), is Buksha’s most recent (and thus far, only) novel to be appear in English. Part fictionalized oral history, part avant-garde stream of consciousness, the novel tells the story of a real military defense factory in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) through the interconnected lives of its workers.

Though a factory history may not sound particularly enthralling, it is not for nothing that the book was awarded Russia’s 2014 National Bestseller Award. Reading “The Freedom Factory” is like peering into a kaleidoscope you turn to see what the next prisms will reveal. Forty short chapters—each containing its own linguistic style and life—bring together excerpted interviews, monologues, film reels, snapshots, and recollections of former and current factory employees. The text spans four directorships, beginning with the factory’s heyday as an economic and cultural hub in the post-WWII years (under Director N), through the Stagnation Period of the 1970s and ‘80s (under Director V), from the U.S.S.R.’s collapse and into the chaotic 1990s and subsequent 2000s, when the factory degrades into a relic of the failed Soviet project (under Director NN and then Director L).

One moment, we’re among women in acid-singed smocks in the factory’s hot-dip galvanizing shop. Another moment, we’re aboard a trade vessel, bobbing along a pink-tinged sea under a greenish sun, headed to Cuba with Freedom’s own first Soviet radar system. Later, it’s four months after Chernobyl and Director V is figuring out how Freedom is going to design and produce a hundred radiation detectors in five days to screen imported Ukrainian and Belarussian fruit. But reappearing characters—some of whom stay with the factory till the very end—connect these seemingly independent prisms into a whole.

Though it is a fictionalized account, the book is based on (and contains verbatim pieces of) materials that Buksha, in her capacity as a promotional copywriter, collected when writing a brand book for the factory’s current-day new management. Characters speak to a muted author, who is not so much a narrator as a fictionalized reporter, the shadow of whom we only glimpse when speakers echo her questions (“How he died? There’s kind of a legend about that…”) or address her (“But you can’t write that down, because the names of people associated with the factory have to be encoded in Latin letters”).

Russian critics have pointed to the paradox of someone who came of age in the post-Soviet period—and has worked as a day trader no less—writing about the Soviet factory experience. Indeed, the novel not only occupies a special place in Buksha’s work, which usually takes place in the post-Soviet years, but in contemporary Russian fiction as a whole. A number of award-winning Russian novels of the last decade reexamine the hardships of the Soviet period while blurring traditional victim-perpetrator divisions (such as Eugene Vodolazkin’s “Aviator,” Guzel Yakhina’s “Zuleikha,” or Zakhar Prilepin’s “Monastery,” for example), but Buksha’s novel does this by reprising an unlikely genre—the Soviet production novel.

Unlike Western factory novels, which exposed injustice (such as Upton Sinclair’s 1906 exposé of Chicago’s meatpacking district, “The Jungle”), the Soviet production novel—the literary centerpiece of the U.S.S.R.’s official aesthetic style, Socialist Realism—depicted workers’ willingness to endure deprivation in the name of industrial progress. Valentin Katayev’s “Time, Forward!” (1932), for example, which was based on the author’s own experience visiting a construction site in the steel-producing city of Magnitogorsk, chronicles a brigade’s efforts to break the Soviet Union’s current record for cement pouring. (The workers succeed, of course, only to be immediately outpaced by another factory, thereby illustrating the lightning pace of Stalin’s first five-year plan.)

In many ways, the voices of Buksha’s novel pick up where these frenetic accounts leave off, only it’s a few decades later when the Cold War is in full swing. In Chapter 7, “The Lily,” Director N announces that he needs four data link targeting systems (Lilies) for the U.S.S.R.’s Yak-28L tactical bombers in two weeks. Upon negotiating the necessary conditions (a 299-ruble salary, cots, and, of course, an endless supply of hooch), the shop workers, “three sheets to the wind,” meet the deadline—a veritable industrial triumph.

“The Freedom Factory,” however, is just as much about the Soviet project’s construction as it is about its collapse. Not surprisingly, the Lilies, which are “slapped together any which way,” don’t work when they are installed in the planes. But shoddy workmanship and missed potential are beside the point. The novel lays bare the complicated junctures of disillusionment and nostalgia, cynicism and hope, and comedy and tragedy.

The novel’s multitude of voices, linguistic styles, and cultural specificity make for a tall order for translator Anne O. Fisher, who is no stranger to challenging texts. (She is the award-winning translator of Ilf and Petrov’s NEP-era comedic novels, “The Twelve Chairs” and “The Little Golden Calf”). Fisher expertly maneuvers between shop-floor banter, bureaucratic jargon, bucolic scenes, and even outright gibberish. When a tedious meeting about a new factory intensification program sputters into nonsense, Fisher renders garbled Russian obscenities with aplomb: the factory, a voice booms, will “meet and exceed the demanding dongstrds fu kniduction and bu do nof goods for hapular ass! In short, comrades, Fintensification-1991 begins now!”

In grappling with the novel’s many historical allusions, Fisher occasionally makes subtle insertions or expansions. In the Russian text, for example, when the personnel manager looks over the file of a newly arrived worker, Tasya, he reads the following information: “born 1942, place of birth Leningrad, parents unknown.” He then frowns as he involuntarily pictures frost-covered floorboards and “scraps of wallpaper.” The translation makes this reference to the Nazi blockade of Leningrad clearer with some strategic additions: “Boris Izrailyevich frowns. The Siege. He involuntarily pictures the frost-coated floorboards, the walls scraped almost bare of wallpaper, and the like.” This tactic works well to convey the historical context for the Anglophone reader while still keeping pace with the text.

Rife with laugh-out-loud moments, heartbreak, and arresting lyricism, Buksha’s “Freedom Factory” brings a bygone era to life in all of its madness, harshness, and beauty. And lucky for us, Anne O. Fisher has rendered it in an English text that is just as dazzling as the original.

“The Freedom Factory” Chapter Two: Tasya

Ta-a-asya, Boris Izrailyevich croaks, and the unspoken but undeniable malediction, directed at no one in particular, hangs briefly in the air. So you’re Tasya. Holding her personal file up close to his face, the personnel manager reads: born 1942, place of birth Leningrad, parents unknown. Boris Izrailyevich frowns. The Siege. He involuntarily pictures the frost-coated floorboards, the walls scraped almost bare of wallpaper, and the like. I’m from an orphanage. So you’re fresh out of factory apprenticeship school, then? Yes. Did they send you? Assign you here? No, I wanted to come. I want to work at an electronics factory. Boris Izrailyevich looks up. Why, that’s marvelous! Let’s go, I’ll show you around. Now what kind of job can we set you up with? We could take you on as an apprentice press operator in Shop Twelve. There’s a lot of girls there, you’ll make friends. Oh, yes, I’d like that!

They stride through the courtyard. One limps, the other minces. Gee, who was that? Yes, our comrade C is a big fellow. He’s pretty strong, huh? Yes, he can hoist a lift one-handed. But listen to this: in the war he took out several tanks. He’s been decorated. Gee! Then why don’t we go to him first, what if I like it there?

Lifts. Cables. Pulleys. What’s this, Izrailyevich? She the reinforcements you promised us? Well, it’s just that I happen to have an extra half hour today, so… I’m giving the young lady a tour of the factory. We need more workers. A parts manager, maybe—you don’t need physical strength for that. As a matter of fact, Kostya, may he rest in peace, only had one arm. But he did just fine… Okay, okay, simmer down now. Do you want to be a parts manager, Tasya? You’ll have all these elevators, and lifts, all these neat conveyor belts so you can send out all the components on time? So the devices can be built? What do you say, Tasya? (Her face is tilted up like a little saucer. Her eyes are open very wide. Way up high, where the cable runs through the pulley… all the way up underneath the roof… there’s something white up there…) Um, I don’t think I can, after all… I’d rather, I think I’d rather do that other thing… be a press operator… Fine. We get it. No, really, it’s fine, we’d rather have a regular guy anyway. Cut it out, now; there’ll be another batch coming soon. For sure, I promise you.

They get to Twelve. Hello, girls. Here, I’m bringing you a new apprentice. Let me introduce you: Tasya. So here, Tasenka, is where we make toys. What we do is we press a sheet of plastic, and presto, we get a little toy gun, all ready to go. The presses are new, it’s the most advanced technology. To be sure, it is considered harmful work, press-forming plastic and poly- styrene, by law you aren’t allowed to work here yet, but you can start as a batcher or packager. We have fun here. Look, here’s our changing room, and that’s the shower! And you get milk after your shift. And every so often the labor union gives out free tickets, one time we even saw Lyubchenko herself, can you imagine? So then, you’ve decided, my dear? I can go? Well, hold on a minute… What’s this? You don’t want to work here? Oh, please don’t be angry! It’s just that I still haven’t figured it out. Could I look at some more workshops, please?

Goodness, now who’d go being angry with you? Look around and come back to us! Sure, Tasya, let’s go have a look around, of course. Just not for too long, I don’t have much time.

So what was that?! What’s going on?! I don’t want to make toys. Get a load of that! What’s with you?! What’s with these whims?! I want to work at an electronics factory, I don’t want to make toys. Well, well, well, Tasenka… Hmm… in that case… we’ll head over to the machine shop, then. That’s in Nine. But I’m warning you, it’s an all-male collective. Nobody’s going to coddle you there. You’re not afraid of hard work, are you? What about sharpening your cutter, will you be able to do that yourself? Well they’ll teach me, won’t they, Tasya whispers rapturously. I want to work a machine! And I will! Well I’ll be. She’s going to work a machine. Fine, let’s go.

How-de-do, Izrailyevich! And what’s that you’ve got there? Tasya!? What kind of a name is that?! That’s what they called you in the orphanage? No way, we don’t like Tasya. We’re gonna promote you to full Anastasiya. One letter for every inch you are tall! Ha-ha-ha! Where are those benches we had around here? Z made some benches, remember? ’Cause she’s gonna need two! So what do you think, Tasya? Like it here? That’s my girl! Now fellows, you better watch your mouths… and by the way, she’s going to be a lathe operator, just like you all. That’s what I’m saying. Now look over here, Tasya, here we have comrade K, for example. He also started just like you, back when he was still in school, and now he’s up there on the wall of fame every quarter. Show her the kind of parts you make. Gee, they’re teeny-weeny! Neat! You like that? You want to make ones like that? I do… but… I just…wait…

Hell’s bells. Tasya. What am I waiting for?! I’m not going to get anything done today with you around. That does it, Tasya, I don’t know what to do with you. You don’t like it here, you don’t want to go there… I don’t really like people like you very much, you know? Capricious people. You know what? Seeing as how you came to work, then you don’t get to pick where, you just go where you’re told. And incidentally you won’t get a whole lot in the way of choice here. I’m the one who’s just going around coddling you, damned if I know why. That’s it, we’re going back to Shop Twelve, and basta. Oh… no, no, no, no, no, now don’t go doing that, I really just can’t stand that, what’s with the waterworks…

Greetings, Boris Izrailyevich, what’s all this racket over here? Well see, this little lady came to work at our factory. Her name’s Tasya. I’m taking her around, showing her everything. But she’s all, I don’t want to do this, I don’t know how to do that. Hmm. I see. Boris Izrailyevich, you can go back to your office. I’ll update you later on the labor assignment for comrade… what’s your last name? Comrade M. Now then. Where would you like to work? At an electronics factory, that I understand. What would you like to do? Every day?

I like designing and building things. Designing things? So that means you like tinkering with mechanisms, is that right? Yes… once at the orphanage I even fixed a clock. You fixed a clock? Yes… and I got first place in the model competition with a working model excavator, I thought up a way to build it so that it really would dig, all you had to do was push it a little and then it’d dig for two minutes. It could dig for two minutes? The excavator could really and truly dig? And what did it dig, if it’s not a secret? Sand. I’ll bring it in and show you, if you want me to. Please could I work in a shop that designs and builds things? Please! Even just as an apprentice, I can do the work, honest I can!

Hmm. Well, here’s what I’m going to tell you. We do have a shop like that. It’s called the assembly operations shop. What they do there is they put parts together to make subassemblies, then they put those together to make devices. That’s this workshop, this one right here. Now hold on a minute, don’t celebrate! You need a high-school diploma to work here. Do you understand? And you still have two years to go until then. Three, you say? Mm-hmm. Well, all right. Come on.

Hello, comrades. There’s someone I’d like you to meet. This is comrade M. She’s going to work with you as an ap- prentice assembly fitter. That’s right, she will be the first young lady in your shop, and so I’m going to ask that, as her comrades, you take her under your wing and treat her with extra sensitivity and loyalty. If the foreman tells me a month from now that you’re not up to it, Tasya, you’ll go work wherever Boris Izrailyevich sends you. Without a peep. Deal? Deal! Thank you so much, sir! But—what’s your name? Have that model excavator in my office first thing tomorrow.

Chapter Three: The People’s Brigade

Ekaterinhof Park is covered in bright white bird-cherry blossoms. The petals hang layered in the air, puff up in little powdery heaps, float in lacy rafts down the river, swirl in the dust. Even after five o’clock the sun still stands above the warehouses, cranes, and iron roofs. It’s spring (sharp, brilliant smells; breezes; reminders; bird-cherries and fried fish; rank rot and fresh breezes; the neighborhood’s poverty; the clattering of sharp, rusted roofs), the air is maximally saturated, so you stop feeling hunger, cold, fatigue, and pain, and all that’s left is a fevered, insomniac receptivity to happiness, an urge to continually switch activities, flowers, faces; it’s the vibrating, liquid, prismatic air of frenzy. A woman bashes a man in the head with a piece of rusty pipe, blood pours in a sheet down his cheeks, and he smiles blissfully. In the housing blocks, the little eight-year-old daughter of momma Svetka the building caretaker sits in the entrance and tells scary stories, while her baby sister Vika squats in her tattered, peeling sandals on the ground, methodically spitting on the grey asphalt dust and smearing it around with her finger.

Man! Isn’t there a fight somewhere? My hands are itching, couldn’t somebody somewhere just have a good fight today? We should sic the people’s brigade on you, Pasha! You should work harder, then you wouldn’t have so much extra energy. Guys, I have a plan (pulls a half-liter beaker out of her bag). Whoa there, Tanya, where’d you dig that up? I asked the measurements and standards guys, I told them what it was for and they gave it to me. What’s it for? Well this is what it’s for (tells them). So let’s just drop by. I’ve suspected for a long time now that they’ve been pouring short. Now Pashka, just where do you think you’re going? No, we’re not taking you with us anymore. We’re keeping things reasonable. You will stay behind and keep a lookout. That’s even better: what if there is a fight?

Could we have some juice please? (Three glasses of 200 milliliters each. Tanya produces the beaker.) What’s that you’ve got there? Don’t worry. We’re the people’s quality control. (Valya’s a detail man, he makes the smallest parts in the whole factory on a lathe so small the workshop nicknamed it “the alalaika.”) Now don’t you go worrying about anything. The third glassful easily fits in the beaker on top of the first two, and at this point Verrrrka takes center stage. Her voice vibrates threateningly. So. A half-liter beaker! And it all fit! Three 200-millileter glasses! Call the manager, we are going to officially document our audit. That’s right! shout shoppers. We’ve been seeing this for a long time! Don’t give me your “just wait a minute,” Verka hammers out. We didn’t come here to wait! We came to establish that you are pouring short! And we are establishing it! We don’t want anything from you (Valya). Now don’t you worry. Everything’s going to be okay. But you just can’t do that. You see? That’s why we’re documenting our audit. Because people want to have some- thing to drink. But you pour short. Yes, that’s right, everyone says approvingly. That’s what we want! But you pour short! We’ve been noticing this ourselves for a long time now! But if nobody’d come to you with a beaker, you’d’ve kept right on pouring short! Those who act with impunity will suffer punitive measures! That’s right! Good for these guys.

The saleslady turns sour. (Pashka peeks through the door- way. This is just the right time. Would be the right time. But Verka is watchful. She brandishes her fist at Pashka. Pashka promptly assumes an innocent expression: what?)

The four of them walk down the damp, fresh, warm street. Pashka, is it true that you’re a former city boxing champion? What do you think? Everybody knows I am. And know who my buddy is? A! We were at the same trade school, we roomed together. How could you not have heard that? Well, that’s just ’cause you’re not interested in boxing, but he’s like… he’s famous! His fame’s resounding everywhere these days. He even took out that world champion, Savage Hugh; he took him out in the first round. And you slept in the same room as him? Weren’t you afraid? That’s right, we used to jump up in the middle of the night and spar, and sometimes I even laid him down on his back, no sweat, lies Pashka. But you just try to get me flat on my back! Verka bristles and puffs up, right in the middle of the street. She’s solidly built, thick-set, and her eyes are foreboding, crazed; she’s not joking. Yeah… I’ll lay you on your back, no doubt about it, says Pashka in a way that makes Valya blush a little, while Tanechka snorts indignantly to herself and adjusts her glasses, but Verka doesn’t give a rat’s ass. Come on, then! she shouts, and runs at him. Pashka grabs her lazily, but carefully, in the middle of her dress and throws her over his shoulder, where she kicks and bucks, playing the game that’s as old as the earth itself… but suddenly Pashka fixates on something… he tests the air… then he plops Verka back on the asphalt, not noticing that she’s lost a shoe, and races off. Tanechka: somebody’s started a fight. Let’s give the guy a chance to do what he loves best.

Verka (hopping over to her shoe on one foot): hey, wait for me!!

Pashka’s already deep in the thick of it. Valya K peers in, but no matter how hard he tries, he just can’t figure out who’s beating who. And how did Pashka figure it out, off the cuff like that? He didn’t figure out a damn thing, he’s just hitting whoever his fist lands on, that’s all. Valya, hadn’t you better go help him? Well isn’t that some great advice! Don’t go in there, Valya! Girls, I love you so very much, says Valya K. Jeez, I’m trying to look out for you, and you go and smart off. You’re just afraid to fight. You abandoned your friend when he was in trouble! Then I’ll go in myself! Verrrrka flies over to the fight and grabs one of the fighters by the neck from behind. This surprising dirty trick makes him lose his balance, and he almost falls backward. Verka lets go and jumps away. As she approaches the fight, Tanechka loudly says “a people’s brigade.” And this is where it all stops. Not all of it, of course; the commotion goes on for a long time, what with the building caretaker having gotten dragged in, as well as an old shrew with scratched-up legs, and a mom ignoring her many children to pour oil on the flame from her window, but then a Pobeda pulls up and a solid-looking comrade climbs out, and it’s not clear who the comrade is, but in the end the conflict is diluted and drains away. Pashka, excited and rumpled but virtually unscathed, is gesticulating and yakking about some- thing. By now the sun is disappearing behind the buildings, and the lindens’ gigantic leaves hang almost motionless in the air, and the air smells fresh: there’s going to be a storm.

The granny with the scratched-up legs runs, shuffling, after them. Dearies, Komsomol members, help me! My daughter-in-law is sick. Grandma, call a doctor if she’s sick. We’re a people’s brigade. What? A doctor? What doctor!? No doctor can help her. Come with me, I beg you by Christ the Lord, help me… she’s young, but she’s dying… she’s going to die. Don’t say Christ the Lord, Valya K retorts, but we’ll do it. We’ll come and figure out what the problem is.

They follow the granny. We live in a corner, half a room, we got no space, and here I am with two sons, used to be four but my youngest died in the war and the oldest went missing without a trace, and now two live with me, and the younger one, he’s like you, he’s finishing high school, he’s working, but the older one, well he drinks, he got married and he drinks, and now he’s made his wife… I don’t know how to say it… we got no space, but she wanted a baby so bad, and like he says, she tricked him… so he goes and makes her… it’s…

Get an abortion (Verrrrka.)

Yes… and he beat her, and threatened her, and he… well, he broke her spirit… she went and did it… and all she’s done since then is lie there, she never eats, she almost never sleeps… she just lies there, no work, no nothing… we had a doctor already, what’s the use in doctors… we got a good one, God bless her… she said okay, we’ll take her to the psych ward, we can take her, you know, but then, well, you know yourself what that means… and she tells us, you need to bring her out of it as soon as possible… she needs happiness… but where are we going to get that… what kind of happiness can we give her…

The granny frets. The door is open. The ceiling is low, and there’s a burnt, damp smell. Had there been a fire? It’s dark. A smoky, greasy kitchen, thronging with women in cheap floral-print dresses. A bevy of ragged preschoolers that pushed into the building after the brigade raises a racket in the narrow corridor. The narrow “half-rooms” lie off the corridor. Pashka doesn’t go in, he stands in the doorway. The meager square meters are heaped with things, packed with furniture. Hello. We’re a people’s brigade. Someone brought us…

Why?

Well, we don’t know why ourselves. Leave.

She turns to the wall and pulls the blanket over her head.

Out past the smeared window in its unpainted, dried-out frame, the sleepy, dusty stillness is growing dark. But it’s not night: in Leningrad, May brings white nights. No, this is a storm coming in to the Narva Outpost from the sea. At the very last minute before it hits, a yellowish light bursts from low on the horizon, filling the streets.

Out of nowhere, Valya K remembers where and when he saw such a strange light: when he was little and they were leaving Leningrad by barge. Look, Valya’s older brother said. Valya turned toward the city and saw above it a fantastical, ominous sun, its glare resounding against the black sky. Mama, is that the end of the world? asked Valya. That was the night the Badayev warehouses burned… and with them most of the city’s flour and sugar… on the eve of the 900 days… The barges were being bombed. The one that left before theirs went down with all its passengers.

Verka, her face dark, stares out the window. Pashka has turned back into the gloom of the corridor and is digging in his pocket, extracting the sugar cubes he filched from the factory cafeteria and passing them out to the small fry.

Excerpted from “The Freedom Factory” by Ksenia Buksha, translated from Russian by Anne O. Fisher and published by Deep Vellum/Phoneme Media. Used by permission.

The Russian novel was published under the title «Завод ‘Свобода’» published in 2014 by OGI. © Ksenia Buksha 2014. © English translation by Anne O. Fisher 2018.