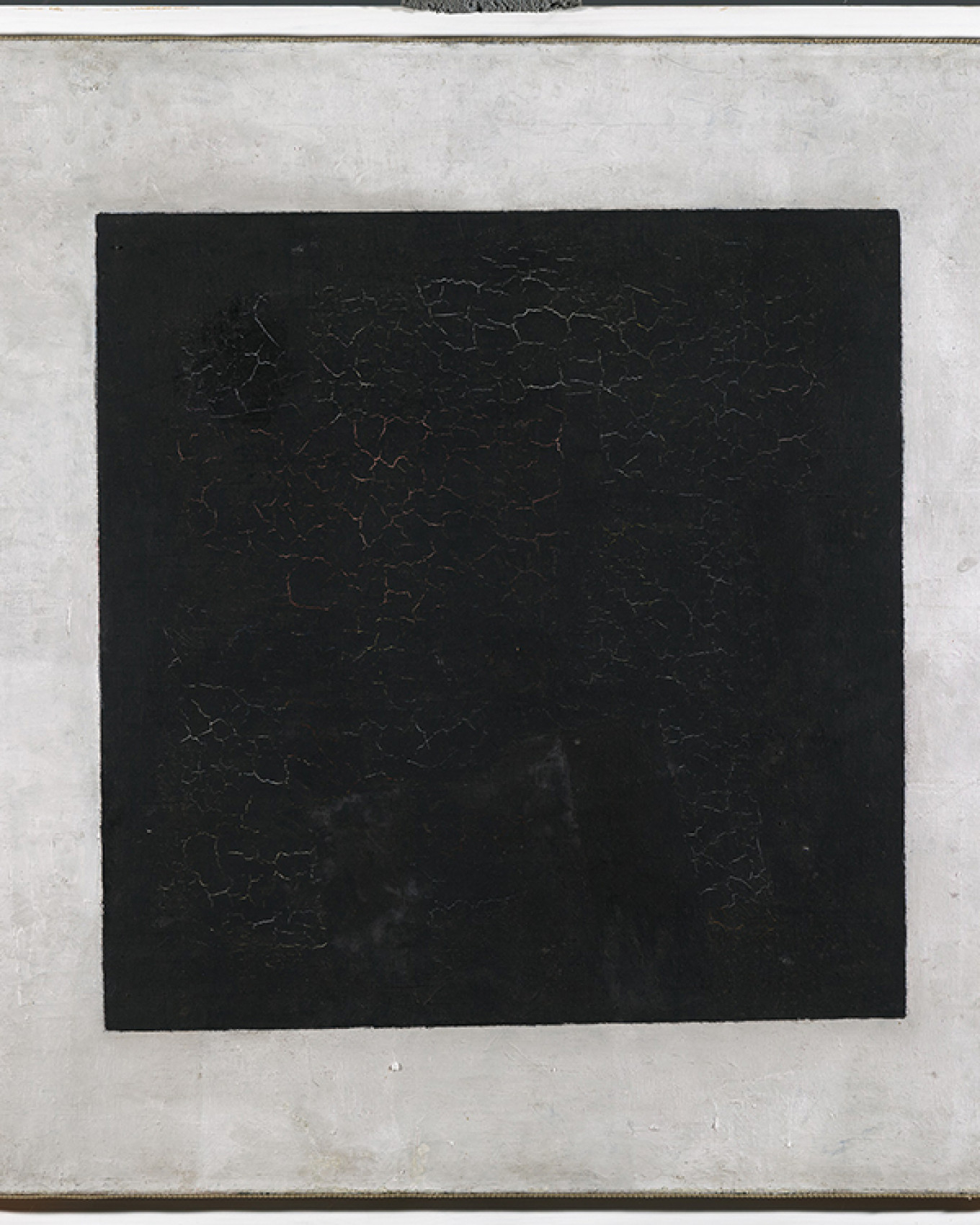

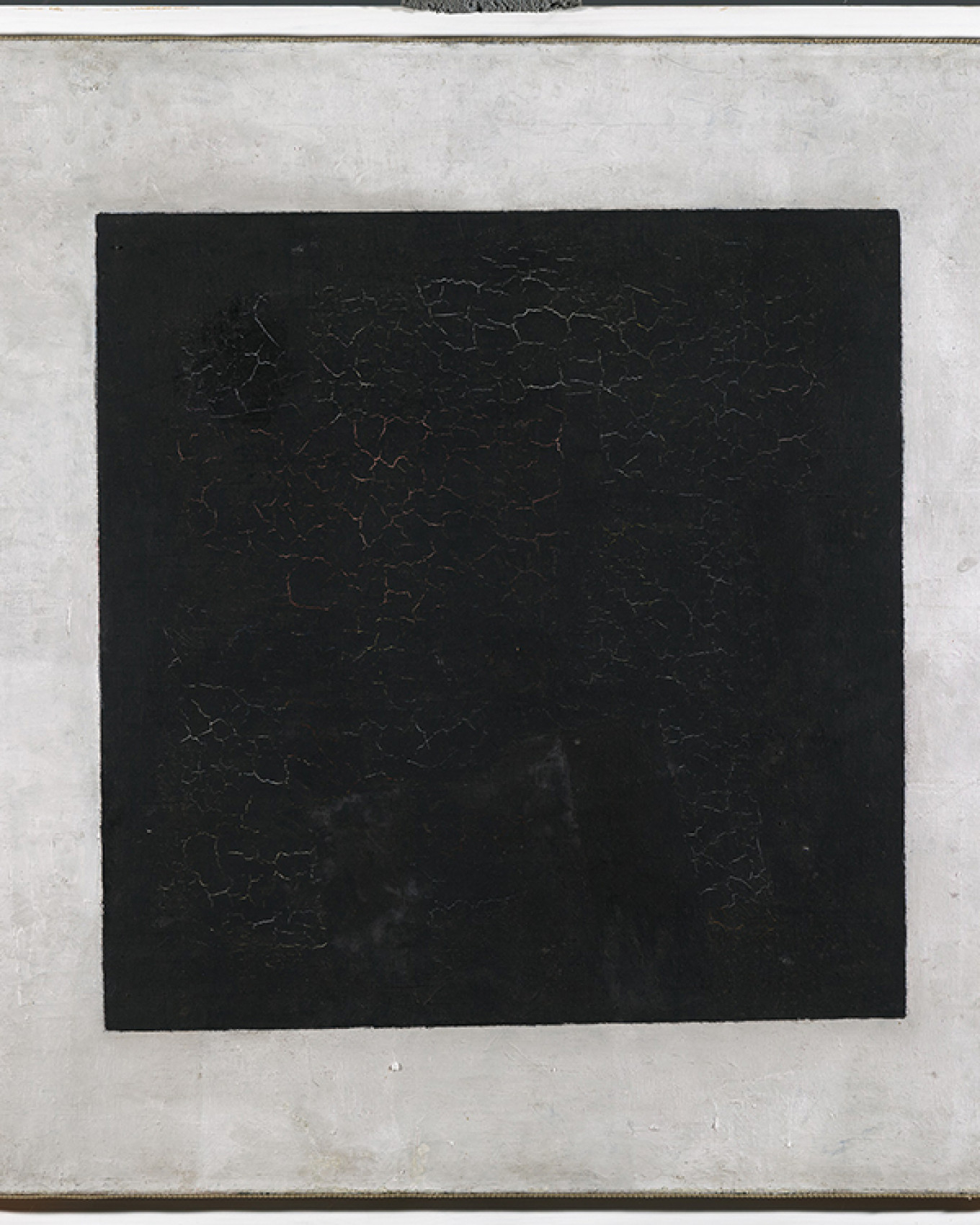

Zelfira Tregulova, the director of the Tretyakov gallery, vividly recalls the first time she saw Kazimir Malevich’s iconic 1915 painting “Black Square.” “It was in 1974, I remember the shock.” As an art history student at Moscow State University, she first encountered the painting in the Tretyakov Gallery, albeit not hanging in the airy exhibition halls, but locked away in the dark storage vaults. The painting was unlike anything she’d ever seen. “I couldn’t have imagined that such things existed, that art could be like that.”

Fast-forward 45 years. The “Black Square” now hangs in the New Tretyakov, in a room devoted entirely to Malevich. Internationally recognized as a masterpiece, it nonetheless still remains under-visited. The gallery has faced enduring difficulties in attracting visitors to its collection of early twentieth-century art. The exact footfall in Malevich’s room is difficult to track (the Tretyakov’s ticketing system includes access to the permanent collection within the price of a temporary exhibition ticket), but Tregulova is clear that available data shows that it “is not enough, it is not enough for such a collection.”

When she became director in 2015, she emphasizes that “one of the first tasks” she set herself was “to bring visitors to this building.” To this end, an extensive renovation project began in June 2018, during which time ten exhibition halls were restored. When they reopened in August 2019, their avant-garde art was arranged according to a modernized new rehang. But is this enough to generate interest in art which spent decades gathering dust in the depositories?

There and here

The relative lack of audience for Malevich in Moscow is ironic, given the crowds his name attracts into international art galleries. The Malevich retrospective held in London’s Tate Modern in 2014 helped the gallery to achieve the highest attendance rates in its history. This is proportionate to the reputation Malevich and his peers have in the canon of art history. The group of radical young artists who briefly rose to prominence around the time of the Russian Revolution are celebrated as some of the original innovators of abstraction, as pioneers and prophets of the course of twentieth-century art. But while this makes them reliable bait for blockbuster exhibitions abroad, this sacred-cow status has never completely transferred to their home turf. “When we do exhibitions of the avant-garde, from the very beginning, we know that the attendance will be three or four times lower [than other Tretyakov exhibitions]” Tregulova acknowledges. Such disappointing ticket sales buck a trend in the Russian art scene, which shows a sharp uptake of interest in historic works by Russian artists.

The Tretyakov’s overall visitor numbers have been boosted by a spate of “sensational exhibitions” in recent years, which smashed records and saw long lines of visitors queuing for hours in the biting cold. The frenzy began in 2015 with a retrospective of fin-de-siècle painter Valentin Serov. In three and a half months, almost half a million visitors attended, making it the most successful exhibition of any Russian museum, ever. A televised Putin visit boosted ticket demand to such an extreme that visitors broke down the gallery doors in their haste for access. The follow years, records were broken again, as a 2016 show of the seascape painter Ivan Aivazovsky attracted 600,000 visitors, numbers which were matched by 2019’s Ilya Repin exhibition. When, last year, a retrospective of the landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi was launched, the Tretyakov website sold tickets with a warning that visitors would expect queues of up to eight hours.

Such statistics speak to an overwhelming appetite for homegrown Russian artists, albeit of a specific strand: nineteenth-century realism. Why, then, does this demand abruptly cut off when it comes to the masters of early modernism?

Several factors come into play, including the lingering legacy of Soviet education. While Repin et. al. have been staples of any Russian school curriculum for generations, Malevich and his peers were all but written out of history under the cultural consolidation of Stalinism. “For decades this art didn’t exist for the people here,” Tregulova explained, adding that this lack of exposure translates to continued confusion today, “people still really didn’t know what it means, this art of the twentieth century.”

Education is essential because this art is the very opposite of accessible. The avant-garde are a complex mix of politics and theory, a response to a rapidly-changing world which is easily misunderstood and easily trivialized. Few paintings could have provided as much fodder for the ‘my five year old could have done that’ argument as the “Black Square.”

Drawing in the skeptical

The Tretyakov curators, however, are committed to changing public perception because, as Tregulova notes, “the Tretyakov collection of the avant-garde is really unrivalled.” Several educational efforts have been launched under her tenure, amongst them the recent renovations, which have introduced thematic halls for individual artists, each telling a clear story about how the Russian avant-garde changed the history of “not just Russian art, but world art.” Tregulova believes that attracting visitors is contingent on offering them new ways to understand historic works of art. Indeed, she credits the recent craze of the nineteenth-century exhibitions as not merely symptomatic of a zeitgeist-fueled appetite for realism, but as “mainly due to the new exhibition policy.” The innovative research of her curatorial teams meant that “every exhibition was a new step in the interpretation of the art of these artists.”

The idea behind the Aivazovsky exhibition, for example, was to illuminate this he was not merely a “commercial, salon artist” but also “a metaphysical artist.” It was a conversation with artist Anish Kapoor —who, Tregulova notes, was “mesmerized by his [Aivazovsky’s] paintings” during his visit to the Tretyakov — that inspired this approach. The curators chose to display Aivazovsky’s seascapes alongside contemporary Russian video art as a “bridge between his metaphysics and the metaphysics of contemporary art.”

It was important that the exhibition “helped young people to understand that Aivazovsky was not just this sweet painter of sunrises and sunsets,” but that “he was thinking about the basic elements out of which the world was created. He was a philosopher,” Tregulova said.

A similar revisionism applied to the Repin show, where the curators also sought to demonstrate “a deep religious connotation, as with the writings of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky” throughout his oeuvre. “No one had seen that in Repin before” Tregulova explained, emphasizing that these retrospectives were not merely an opportunity to showcase a collection, but to actively explore and challenge it, to find new ways for contemporary viewers to engage with the classics.

Tregulova is going to try a similar strategy with the avant-garde. “We are ready to present a new concept of the avant-garde through exhibitions.” Indeed, a special show is currently on display at the New Tretyakov, looking back at the history of the avant-garde. “We are writing the new history of Russian art with these exhibitions, finding in these artists something which people didn’t see before.”

Wider trends show that attitudes are slowly changing. Tregulova highlights the winter Olympic games opening ceremony in Sochi in 2014 as a significant moment for public awareness of Russian modernist to art. Prior to this “nobody in Russia, except a few intellectuals, considered the avant-garde as something they should be proud of, or a special achievement. This ceremony showed everybody that the Russian avant-garde is an incredibly interesting cultural phenomenon.”

The gallery is continually trying to capitalize on this growing awareness through public exposure events. A 2016 project on the Moscow metro brought avant-garde art to everyday life. In 2017, the Tretyakov hosted a centenary exhibition of the art of the Russian Revolution. “We knew that there would not be more than 100,000 visitors, but we knew that it would become an exhibition which would become a mighty step forward in presenting the art of that time,” Tregulova said. Cumulatively, she notes that these efforts have been successful. Visitor numbers are rising and the recent renovation of the permanent collection is “starting to attract a lot of attention.” She admits, “there is a lot to do and a lot to achieve,” but progress is moving in the right direction.

Training the eye

But progress is still moving slowly. One afternoon, gallery visitors to the avant-garde halls continued to be frequently perplexed by Malevich’s exhibition hall. “It’s sort of pointless” Galina Volkova, a beautician observed with a shrug. “I’d say I dislike it more than I like it.” Meanwhile, Gennady Sidorov, 57, was visibly baffled by the art on display. “I don’t understand it, I don’t really like it.” Another museum-goer, Lyudmila Petrovna, a 42-year-old designer, acknowledged the artist’s weighty cultural legacy. “I’ve read a lot about the square, and when you do that, you understand why it’s so significant — it was a political statement, a protest, a new type of art.” She conceded, however, that without her autodidactic investment she would have been lost. “When you look at it, it’s literally just a square.”

Nonetheless, Alexei Bogdanov, a 19-year-old university student, was enthused. “We learn about Malevich in school, he’s such an important cultural figure, such a famous Russian artist. I wanted to come here to see his work for myself.” Perhaps indicative of a generational shift, he appreciated that “Malevich was important because he was so unique” and saw the value in abstract forms. “You can see their own ideas in them, you project your own thoughts onto them.”

As if to acknowledge this uphill struggle in their current exhibition, the Tretyakov curators have hung Malevich’s paintings alongside pull-quotes from a hatchet job published in Pravda in 1935. Here, an outraged writer complains that “the directors of the Tretyakov Gallery deferentially exhibit such derisory things as Malevich’s ‘Black Square’.” The baffled critic is only able to respond to the painting through spasms of sarcasm. “In a frame, on a white field, is a large black square. How incredibly deep and thoughtful! What advanced technique! What skill! what a bright reflection of our epoch!”

It’s a tongue-in-cheek reference to Malevich’s infamous lack of middle-ground, how he has long inspired a cult-like obsession amongst his devotees, and disdainful dismissal from others. Plus ça change, it seems.

Museum of Pictorial Culture. To the 100th Anniversary of the First Museum of Contemporary Art runs until Feb. 23.

New Tretyakov Gallery, 10 Ulitsa Krymsky Val. Metro Octyabrskaya, Park Kultury. Tretyakovgallery.ru