In 1983 Dr. Harald Lipman came to Moscow as the resident physician for the British Embassy. Yuri Andropov was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the U.S.S.R. and relations between the Soviet Union and the Western countries were particularly tense. After completing his first residency, Lipman returned in 1987 for another ‘tour of duty,’ this time to a country being led by Mikhail Gorbachev into the era of glasnost and change.

Lucky for us, Lipman kept a diary — “just headlines and notes” he says — but enough to trigger the flow of memories, often aided by his wife, Nahid. He has compiled them into a book entitled “Moscow Memories: Memoirs of a Medical Diplomat,” which describes the day-to-day life not only of diplomats, but of Soviet citizens living in Moscow and other parts of the Soviet Union: “D” coupons, Beryozka stores, sterilized glass and metal syringes under a tea-towel, Alla Pugacheva singing “Million Red Roses,” tickets to the Bolshoi. These homely details and observations are an invaluable contribution to the memoirs of leaders and analysis of scholars. Indeed, these minutiae of daily life are the context — and often cause — for the changes initiated by the country’s leaders. The Moscow Times spoke to Lipman about his book and memories.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Could you speak a bit about the contrast the very poor physical reality and the very rich, emotional, cultural reality of those years?

A: Times were hard for Soviet citizens — there’s no question about that. Of course, we as diplomats, were in privileged circumstances… there were special stores for foreigners, the “diplomatic gastronom,” for example. We also would go to the rynok [farmer’s market] quite regularly. We would go to other stores in the Moscow and we got a pretty good feel of what the situation was like. Sadly many of the stores had bare shelves, or something would appear in Moscow, bananas or pineapples or something like that. Then street sellers would have crates of them, and long queues would form. Often people didn’t know what they were queuing for — they just saw a queue and joined it because they knew if they bought something they didn’t want themselves, they could always trade it or barter it with friends or other people.

Q: How did Soviet medicine seem to you when you arrived?

A: I graduated from medical school as a doctor in 1955. Now, when we first went to Moscow in 1983, the standard of medicine in general was equivalent pretty well to the standard as it has been in the early 1950s in U.K. or Western Europe. However, there were certain areas where they were very specialized in, for example, Fyodorov with his method of what would become laser therapy. His methods of treating short sightedness were much more advanced than what we had. Then there were orthopedic surgeons who has had a lot of experience of dealing with trauma during the Second World War. They had techniques that we didn’t use. Of course, in space medicine they were really, in many ways, ahead of us in the West.

Q: You had a project with a children’s hospital in Moscow – is it still ongoing?

A: We had a project with the Tushinsky Children’s Hospital in Moscow. Princess Diana was a patron, and when she died, we decided that we would establish scholarships for Russian doctors to come to the U.K. for three months to be attached to Great Ormond street hospital in London. We ran the scholarships from 2000 until 2019. We had 55 or so scholars over the years from all parts, not just Moscow, but all over the Russian Federation and from Kazakhstan. Nowadays we can’t do that due to COVID.

Q: How much were you able to travel?

A: We did try to travel as much as possible in the Soviet Union. This wasn’t easy because there were many areas where foreigners we’re not permitted to go. Usually we wouldn’t get permission to travel until the day before we were due to go. Then flights were difficult because the administration or the embassy could book a flight out for us, but we couldn’t book the return flight, so we had to arrange when we arrived to ensure that we got a flight back. On several occasions, the flight time was quoted, and we turned up at the airport and realized that they were quoting it on the basis of Moscow time, not on the basis of where we were. We did actually manage to travel and visit many of the republics, as many as we could, even if only for a couple of days. The variety of cultures was quite remarkable and fascinating.

Q: What are your most striking memories?

A: It was very striking how knowledgeable Russian people were about culture compared with similar people in the West. This was quite remarkable. I had to admire them — how they survived in difficult circumstances… they were great survivors.

Excerpt from Chapter Three of “Moscow Memories”

My role at the Embassy was primarily to look after the health & welfare of Brits, Canadians, Aussies & New Zealanders, participants in the Commonwealth Scheme. Additionally, any diplomats from friendly Embassies, some UK language students, some of the small UK business community, and important visitors.

The doctor was on call 24 hours a day. However, a weekend rota had been arranged with the American and French Embassy doctors.

Each month, drugs and equipment were ordered from the Welfare Department in the FCO, and the Embassy could also order bulky medication, such as cough medicines, from Helsinki. Basic laboratory facilities were available in the Embassy surgery, and one could use on request the laboratory technician in the American Embassy. For more sophisticated laboratory tests, specimens were sent to Helsinki in the US diplomatic bag. X-rays were available at the US Embassy and were adequate for limb fractures.

Seriously-ill patients, subject to their medical condition, were ‘medevaced’ to Helsinki, about one hour’s flight away. Local arrangements there were made with the help of a Finnish doctor, Dr Stefan Barner-Rasmussen. Other seriously ill patients might be sent to London or depending on their nationality to other Western capitals. In emergency situations, when the patient’s evacuation was not appropriate or possible, one could refer to the Soviet Medical authorities by telephoning 03 this, however, required the assistance of a fluent Russian speaker.

Rarely, foreign diplomats had to be admitted to Russian hospitals. A part of a specific Moscow hospital, the Botkin, was reserved for foreigners. Most Soviet hospitals were designated by numbers, but a few had names. This hospital was named after Professor Sergey Botkin, a founder of modern Russian medical science and medical education and Head Surgeon to Tsar Aleksandr II, the emancipator of the serfs.

British and American dentists visited the American medical centre in the US Embassy annually, for two spells of three weeks each, and a Canadian dentist visited once a year for three weeks. When no dentist was available, the patient would need to be flown to Helsinki […].

It was well known that Moscow was not an elegant or clothes-conscious city, and there were no shops to enable one to keep abreast of fashion in the West. The main requirement was to dress warmly in the Winter. Thick, warm, full-length wind-proof coats, lined boots with thick soles, warm gloves and a fur hat. Men, women, and children could buy good fur hats, shapkee, in Moscow for £ 5 to £ 10 depending on the fur.

Men were advised to bring out a black tie and women a black dress, required if a period of Court mourning were necessary.

From the Embassy Commissariat, located on the ground floor directly below our first floor flat, we could buy basic requirements, such as fresh milk, butter, bananas, and citrus fruits, which were imported weekly from Helsinki. All purchases were paid for by sterling cheques.

In the city Diplomatic gastronoms, sold dairy produce, fresh meat, frozen fish, poultry, fresh fruit and vegetables, tinned goods and some spirits, wines, and tobacco. Supplies, however, were erratic and in the winter months often in short supply. This was paid for with ‘D’ coupons.

Food, when available, could also be bought in Russian shops and markets for roubles.

*

Sports included a ‘hares and hounds’ chase, known as the Hash House Harriers, which originated in the Malay States in 1938. The Moscow HHH was established in 1983, shortly before we arrived there. The ‘hares’ would lay a trail marked with chalk symbols, and the ‘hounds’ would run, or in some cases, walk the trail. Every alternate Sunday, members of either sex, from different Embassies, would act as ‘hares’ and at the finish entertain all with free beer. The trails were on public roads and footpaths but sometimes ran through private ground, and, not infrequently, the militsiya would appear and caution the runners. Traditionally those who finished last would have to drink their glass of beer in one long gulp without stopping while the other members chanted “down” “down.” A rather childish custom.

Our first car at post in 1983 was a Zhiguli 1300, a Russian made Fiat 124, manufactured on license in a city called Togliatti, named after the Leader of the Italian Communist Party. Togliatti was situated on the Volga about 800 Km southeast of Moscow, and the car plant was the single largest employer in the city.

In the rush to meet weekly ‘norms’, a large number of Russian cars were built hurriedly and poorly, but, thankfully, ours had few problems.

The car was bought from the Soviet State for 2401 roubles and had to be sold back to the State. This we did after a few months for the sum of 2017 roubles, prior to leaving post at the end of our first tour of duty. Not bad for more than six month’s daily usage.

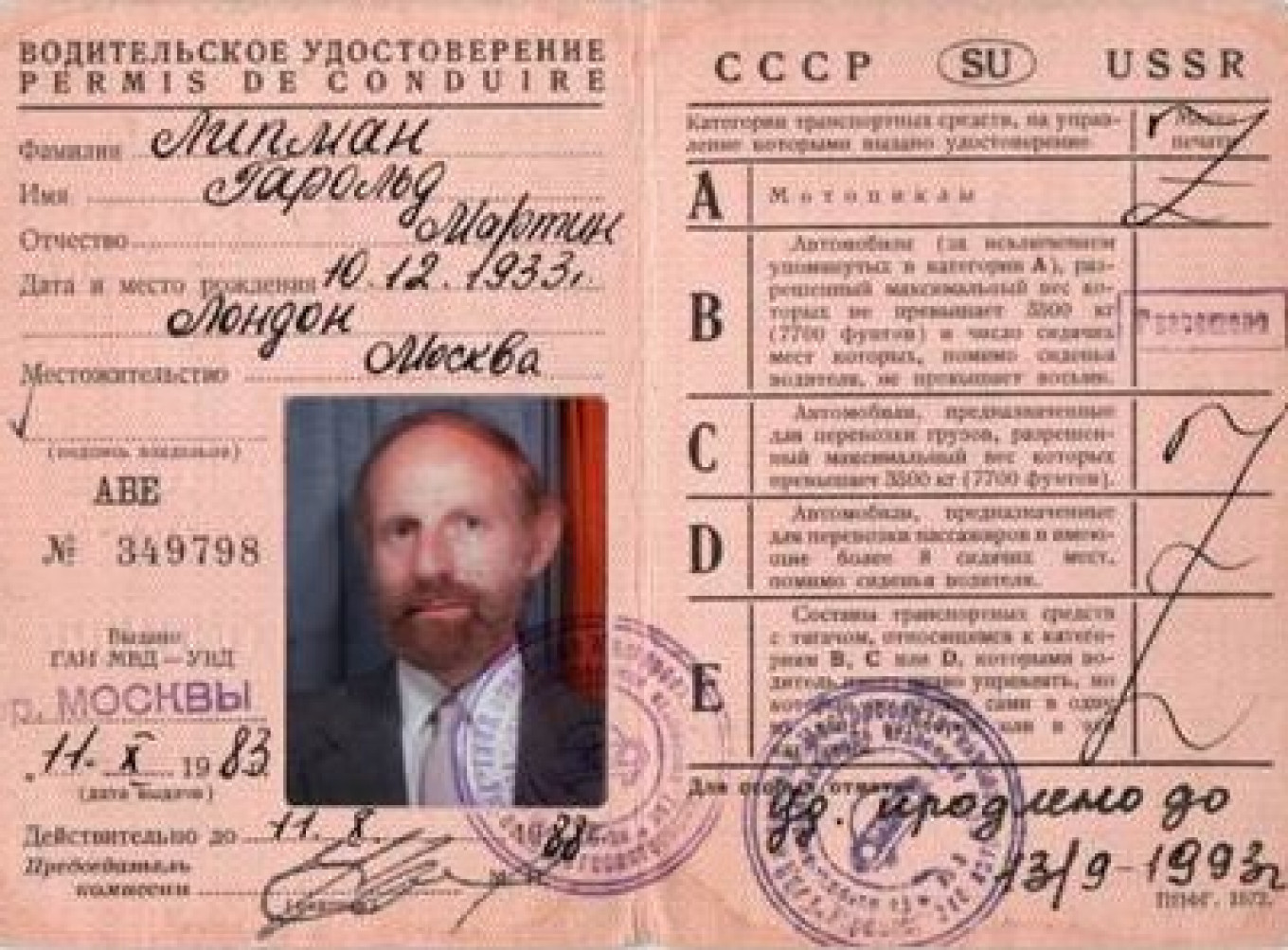

Local driving licenses were issued on presentation of a valid International or British license and two passport photographs. All private cars had to be adequately insured, either by obtaining comprehensive cover from a British firm or from the Soviet insurance organization, Ingosstrakh, which required purchasing separate cover for the driver and the passengers.

Traffic regulations were complicated, and the traffic police, GAI, reported infringements to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. For accidents involving injury to Soviet citizens, Officers might be liable to pay for very large damages. It was compulsory to wear front seat belts.

Studded Winter tyres could be purchased from Helsinki and were invaluable. The Embassy garage staff, dvorniks, would change them when the seasons changed. Cars always required anti-freeze in their radiators to cope with temperatures potentially down to -30 C, and many people would put vodka in their windscreen washers as its freezing point is -24 C.

My licence shows an incorrect year of birth – a small example of the inefficiency of Soviet officials.

Members of Diplomatic Missions were permitted by the Soviet authorities to travel to specified areas within a radius of forty kilometres, without obtaining prior permission. Other journeys had to be notified to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs forty- eight hours in advance. Many areas of the Soviet Union were closed to Diplomats. Travel to distant permitted areas was usually by plane or rail, and both methods of travel were very cheap by Western standards.

Some sensitive areas, for example, near military sites, we were not permitted to drive in. Having lodged ‘flight plans,’ we had to keep strictly to them when driving outside the city. We must not deviate or drive too quickly or too slowly, or the traffic police, the GAI would stop us, and they would request our papers, bumagi. If questioned, they would respond that this was for our safety, as we were strangers and might get lost.

Driving in Moscow was not easy, even though there were few non-official cars, and we had diplomatic privileges. No Soviet street maps were available. Road names were rarely marked other than main roads, and several buildings in the street would share the same street number, as they were built in blocks arranged one behind another. Many of these blocks had been built in the 60s during Khrushchev’s ‘reign’ and were known colloquially as khrushchovki.

Left turns, and U-turns on main roads were only permitted at specified turning places, razvernutki, shortened to ‘raz.’ When we were telling someone how to get to a place in Moscow, we would say drive down such and such a road, and after you have passed the turning on the left, you wish to enter, ‘make a raz.’ You can then make a right turn into the road you are seeking. In Winter, snowy road conditions in the side streets often meant that one could not drive in them.

The CIA had produced the only reliable Moscow street map, which was initially laboriously compiled in 1953. Subsequent editions of the Moscow Street Guide were based on US satellite photos.

Excerpted from “Memories of Moscow: Memoirs of a Medical Diplomat” by Harald Lipman and published by Pectopah Press. Copyright © Harald Lipman 2020 Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For more information about Harald Lipman and his book, see the site here.