Hundreds of works of fiction have been written about Russia in the 1920s: satirical short stories, long novels, documentary dramas by Andrei Platonov, Mikhail Bulgakov, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov. Have you ever wondered why? It’s a good question. Why has this period — certainly not the best from the point of view of official Soviet ideology — turned out to be so “quotable” in literature?

Why did dozens of writers and poets for many years return to it again and again to add vivid images and touches to the picture of life of those years? Everyone probably has their own answer, but we think this period was a subtle psychological point in time that subconsciously affected people.

In March 1921 the New Economic Policy (NEP) was proclaimed by the Bolsheviks to replace war communism. Russia, which was lying in ruins by that time, was in dire need of a new and sensible view of politics and economics. The ineffective requisitioning of food from the peasants, the unprofessional management of industry and commerce, the “revolutionary sailors” in the leadership of the state bank — this disaster was becoming obvious even to the Bolshevik government. In this regard, the NEP became on the one hand a “retreat” from orthodox communist ideology, and on the other hand, a return to common sense in the economy. Unfortunately, it didn’t last long.

Perhaps the most vivid picture of everyday life during that era was left by Mikhail Bulgakov. Let’s leave aside the literary and human aspects of the novel “The Master and Margarita,” which he began to write in 1928. if we just look at the descriptions of everyday life and food, it’s quite surprising. The description of the restaurant “Griboyedov” in this work has become in many ways a classic characterization of “elitist” public catering during the NEP period.

These lines really still mesmerize readers:

“Moscow old-timers remember the famous Griboyedov! Oh, their boiled fillet of pike perch! And sterlet — served in a silver pot, pieces of sterlet covered with crawfish tails and fresh caviar? And little pots of eggs en cocotte with mushroom purée? And in July, when the whole family is at the dacha while urgent literary matters keep you in the city — you sit on the veranda, in the shade of luxuriant grape vines and there, in a golden spot on a pure white tablecloth is a bowl of Potage Printanier?”

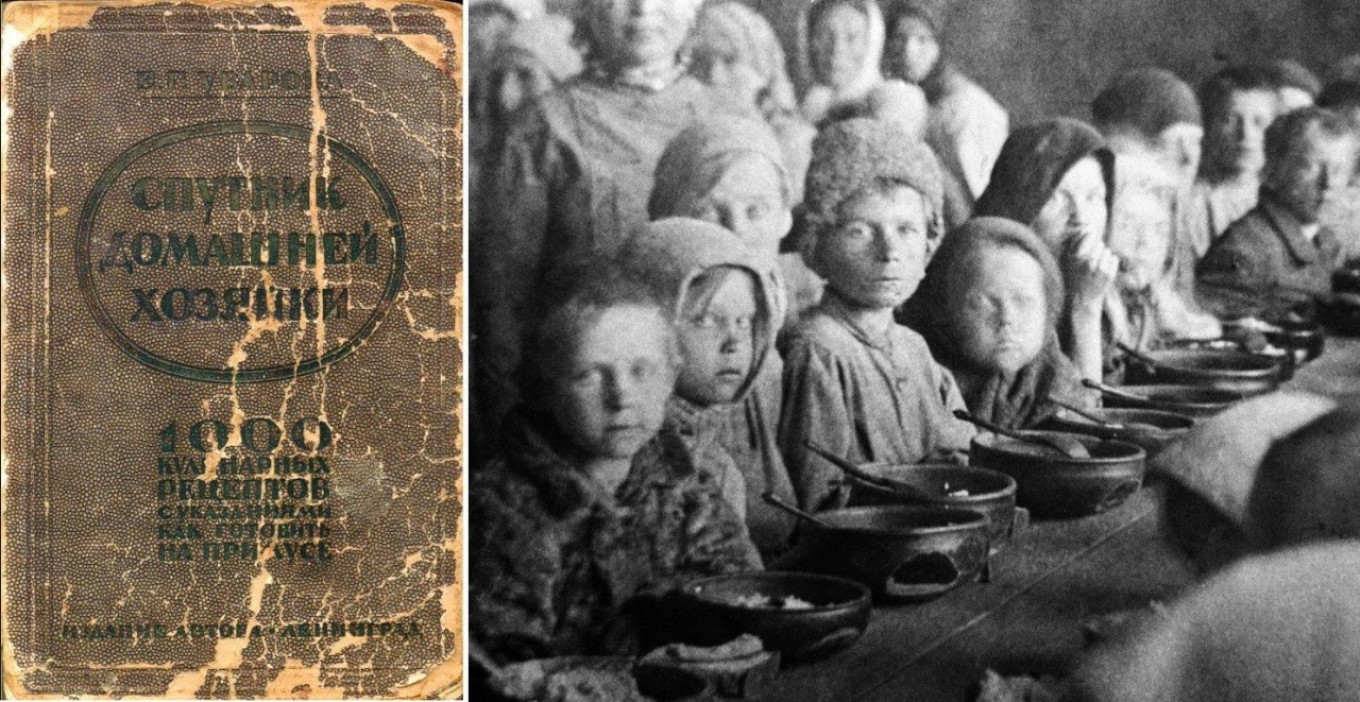

Do you know where those pike perch and sterlet came from? We found the source. In 1927, a very detailed book was published by Yekaterina Uvarova called, “The Housewife’s Companion. 1000 Culinary Recipes With Instructions For Cooking on a Primus.”

In this cookbook we found almost all the dishes mentioned by Bulgakov. This is like a more detailed description of what Bulgakov wrote in “The Master and Margarita”:

“Boiled sterlet. Scale the spine and sides of the fish, gut it through the belly. Make a cut near the tail and carefully pull out the spinal cord with a needle or knife. Wash the sterlet, put it in a fish cauldron with onions and spices, pour in 2 cups of cucumber brine, add decoratively chopped white root vegetables, sliced cucumbers, pickled mushrooms. When it comes to a boil cook for 15 minutes. Take out the sterlet and place it on a serving dish, remove the skin, cover with cooked vegetable garnish and peeled crawfish tails. Serve horseradish with vinegar on the side.”

Here is pike perch au naturel:

“Take a pike perch, clean and salt it, put it in a pot with cold water with 2 onions, parsley, celery, 2 bay leaves and 8-10 peppercorns. Put the pot on high heat. After it comes to a boil, take it off the heat, place it on the side of the stovetop for 15 minutes. Carefully transfer to a platter and serve with white sauce, mushroom sauce or hollandaise sauce.”

As you can see, pike perch au naturel, sterlet, crawfish tails, mushrooms — here we have the full Bulgakovian assortment. In all seriousness, Uvarova’s book is quite a good description of the cuisine of that period. This was an era when the “hungry years” Russia was so used to collided with a bright new premonition of prosperity and the end of everyone’s troubles. To be honest, this era reminds us very much of the early 1990s in the new post-Soviet Russia. In addition to the difficulties and hardships of everyday life, many people must have felt a sense that they were breaking through to a new world, into a bright period of life.

It’s another matter that this feeling turned out to be very short-lived. And the ghosts of the past — hunger, arbitrary rule, lack of money and hopelessness — have returned again, fated to become the story of people’s lives for many years.

We thought we’d make a dish from Bulgakov’s novel “The Master and Margarita.” In Russian, the word cocotte (кокот) is both a cast-iron food mold and the name of the egg dish cooked in it. It’s also the name of a more complex dish — a hot appetizer of finely chopped mushrooms, chicken or game baked in cream or under cheese. Sometimes it is called “julienne” (жульен), which has also confused foreigners over the decades. Here is our recipe for what Russians call “cocotte” but which for non-Russians might be called Mushrooms Julienne en Cocotte. We’ll make them the more traditional way in separate pots.

Mushrooms “Julienne” en Cocotte

Ingredients

- 300 g (10.5 oz) mushrooms

- 100 g (3.5 oz) cheese (Valio Oltermanni, Havarti or Baby Muenster)

- 3 eggs

- 3 Tbsp sour cream

- butter for greasing the pots

- salt

Instructions

- Rinse mushrooms thoroughly, cut off the stem end.

- If the mushrooms are large, cut them in half. Then put them in a pot, cover with water, bring to a boil, skim off the foam and cook until ready (about 10 minutes). Drain the water and cool the mushrooms completely.

- Heat the oven to 200°C /390°F. Grate the cheese. After the mushrooms have cooled, run them through a meat grinder. (It is very important that they are not hot; otherwise the blades of your meat grinder will quickly dull.)

- Mix everything: mushrooms, cheese, eggs, sour cream, a little salt. It should be a nice, homogeneous mass. Grease baking pots with butter and fill with the mushroom mixture. Place the pots in the oven and bake until a ruddy crust forms. The cocotte will rise, brown, and smell incredibly delicious.

- If you do not have separate pots, you can bake in a rectangular form, and then cut into squares and serve. Be sure that the mass is at least 2.5-3 cm high; if it is not, it will be a bit dry.