On Aug. 19, 1991 the Soviet Union woke up to “Swan Lake” being broadcast on television interspersed with newscasters reading an announcement. The “State Emergency Committee” (Russian acronym GKChP) had taken control in the country from a supposedly ailing Mikhail Gorbachev, who was at a state residence in Crimea. The country would be headed by Vice President Gennady Yanayev and the seven other members of the GKCHP, all conservative Communist Party members.

The timing of the coup attempt, and the coup attempt itself, did not come as a complete surprise to members of the Soviet central or the republican governments. On the next day, a new Union Treaty was slated to be signed that would redefine relations between the “center” and the republics and loosen the ideological binds. The coup was an eleventh-hour attempt to keep the status quo.

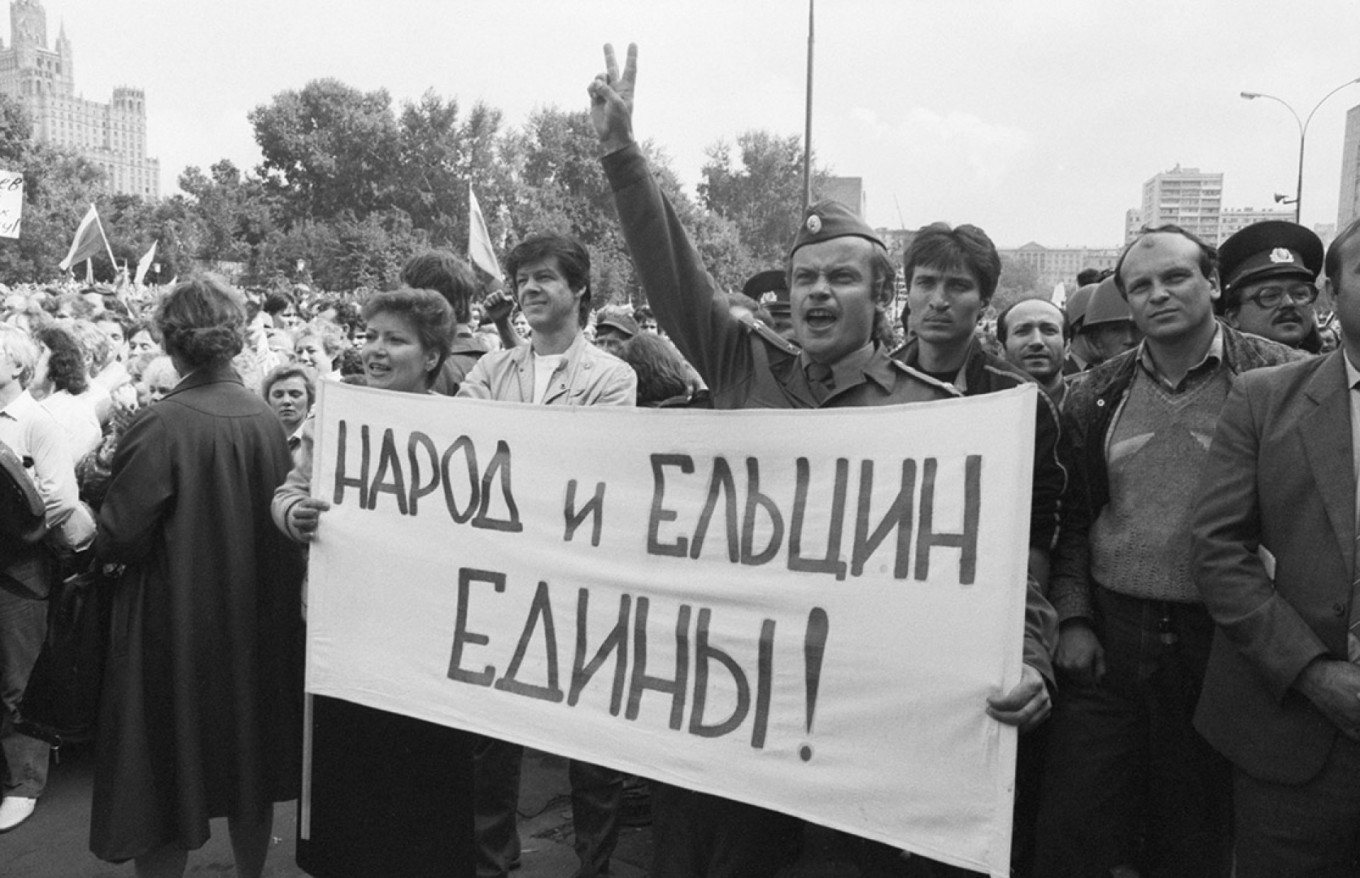

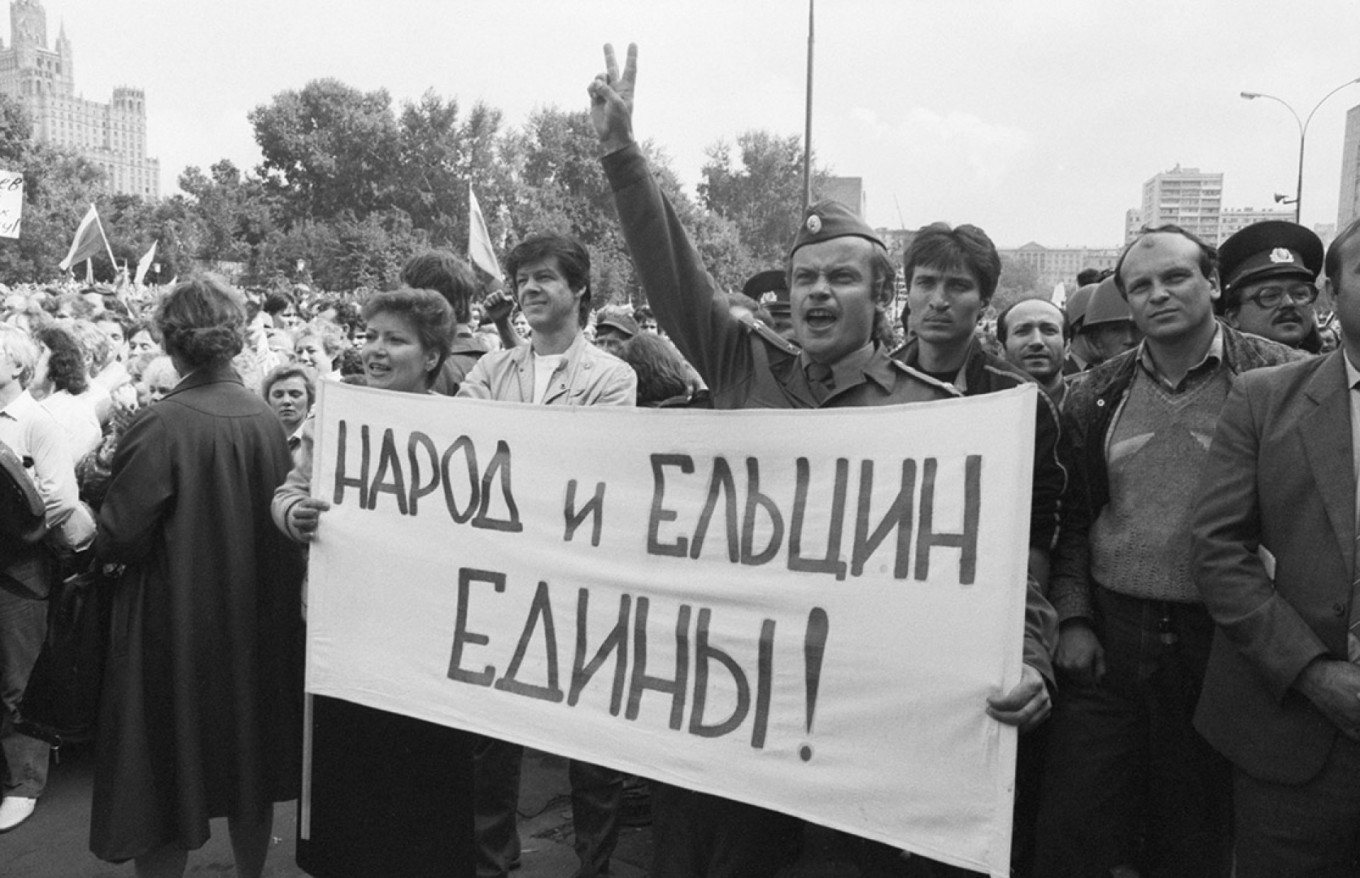

A. Babushkin / TASS

A. Babushkin / TASSHowever, what did surprise the members of the Russian republican government was that they were all at liberty. At an early morning meeting at Boris Yeltsin’s dacha in a compound for state officials, Ruslan Khasbulatov (acting chairman of the Supreme Soviet); Mikhail Poltoranin (minister of press and mass information); Sergei Shakhrai (state councilor); Viktor Yaroshenko (minister of foreign economic relations); Gennady Burbulis (secretary of state); Anatoly Sobchak (mayor of St. Petersburg) and Yuri Luzhkov (mayor of Moscow) quickly wrote up a pubic appeal, called counterparts in other republics, and drove into the city.

At the White House, then the seat of the Russian government, people had already begun to gather and build barricades. Tanks began to roll up and get into position, but in response to heckling from the White House defenders, some of the soldiers got out to talk to them. When Yeltsin saw this from his window, he ran down to join the crowd and read the public appeal atop one of the tanks. The world media got an iconic image, but Soviet citizens saw nothing of this on the now completely state-controlled media. While the future of the Soviet Union was being fought and negotiated in Moscow, much of the country went about their business.

On the night of Aug. 20-21, after many tanks had gone over to the side of the Russian republic, the GKChP took the decision to attack the White House. However, at barricades set up in the tunnel under Ulitsa Arbat to prevent tanks from approaching the White House, three young men lost their lives in a skirmish: Dmitry Komar, Vladimir Usov, and Ilya Krichevsky. The loss of life seemed to bring everyone to their senses. The attack was halted, largely because too many commanders refused to carry out the orders of the GKChP.

By 8 a.m. the tanks began to leave the city. That evening Mikhail Gorbachev and his family returned to Moscow. The next day the putschists were arrested, with the exception of Viktor Pugo, minister of the interior. He and his wife were found in their apartment, having taken their own lives. The remaining conspirators were charged with treason but given amnesty by the State Duma in 1994.

Within the next few weeks almost all the Soviet Republics seceded from the Soviet Union, and on Aug. 24, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned from the Communist Party. The Soviet Union would continue on de jure for another four months, but de facto it had already ceased to exist.