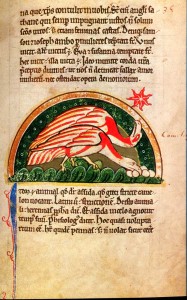

Ostrich /assida, struthiocamelon, struthio/ medallion 10.3×6 cm

In the Latin versions the story of the ostrich which was among the latest additions to Greek “Physiologus” underwent considerable changes. The ostrich does not fly though she has wings. She has feet like those of a camel. That is why the Greek call it Struthiocamelon. She lays eggs when Virgilia /the star of the Pleiades/ is visible; after which she forgets all about them. Though Job explains the behaviour of the ostrich by the fact that God “has made her forget wisdom” /Job. 39:13—17/, and Isaiah mentions ostriches together with dragons, sirens and centraurs who came to make homes on the ruins of Babylon /Isaiah 13:21; 34:14/, the Latin version treats it as a symbol of Man who forsakes all worldly blessings, including his young, and is preoccupied with the divine.

The bestiaries place the chapter about the ostrich in the section on animals, not birds. “Aviarium”, the writing on the moral and mystic meaning of birds composed by Hugh of Folieto, the prior of St. Laurence Abbey near Amien (ca. 1170) includes a chapter on the ostrich /1.37/ containing a detailed interpretation of the bird’s image. In a complimentary light the bird is believed to symbolize a devotee who is preoccupied with heavenly values. On the other hand, the bird is compared to a hypocrite who, like an ostrich having wings but not flying, pretends to be a believer, incapable of living a pious life. Philippe de Thaiin /1245—1304/ and Guillaume le Clerc /2589—2648/ include the story of the ostrich. “The Bestiary of Love in Verse” /2697/ modifies its image, comparing a person in love to an ostrich egg covered with sand; and his sweetheart, to the sun. Albert the Great /XXIII.I.102/ and Brunetto Latini /I.V.I74/ give the traditional story of the ostrich and place it in the section on birds.