A Tale of Two Photographers

Photography, since its inception, has provided an invaluable window into Russia’s turbulent past. The revolutions of 1917 irrevocably altered the course of Russia’s history with seismic political change, but also rendered an entire way of life not only obsolete but also taboo. Historians were left to pore over sepia-toned photos to piece together the vanished and vanquished world of imperial Russia.

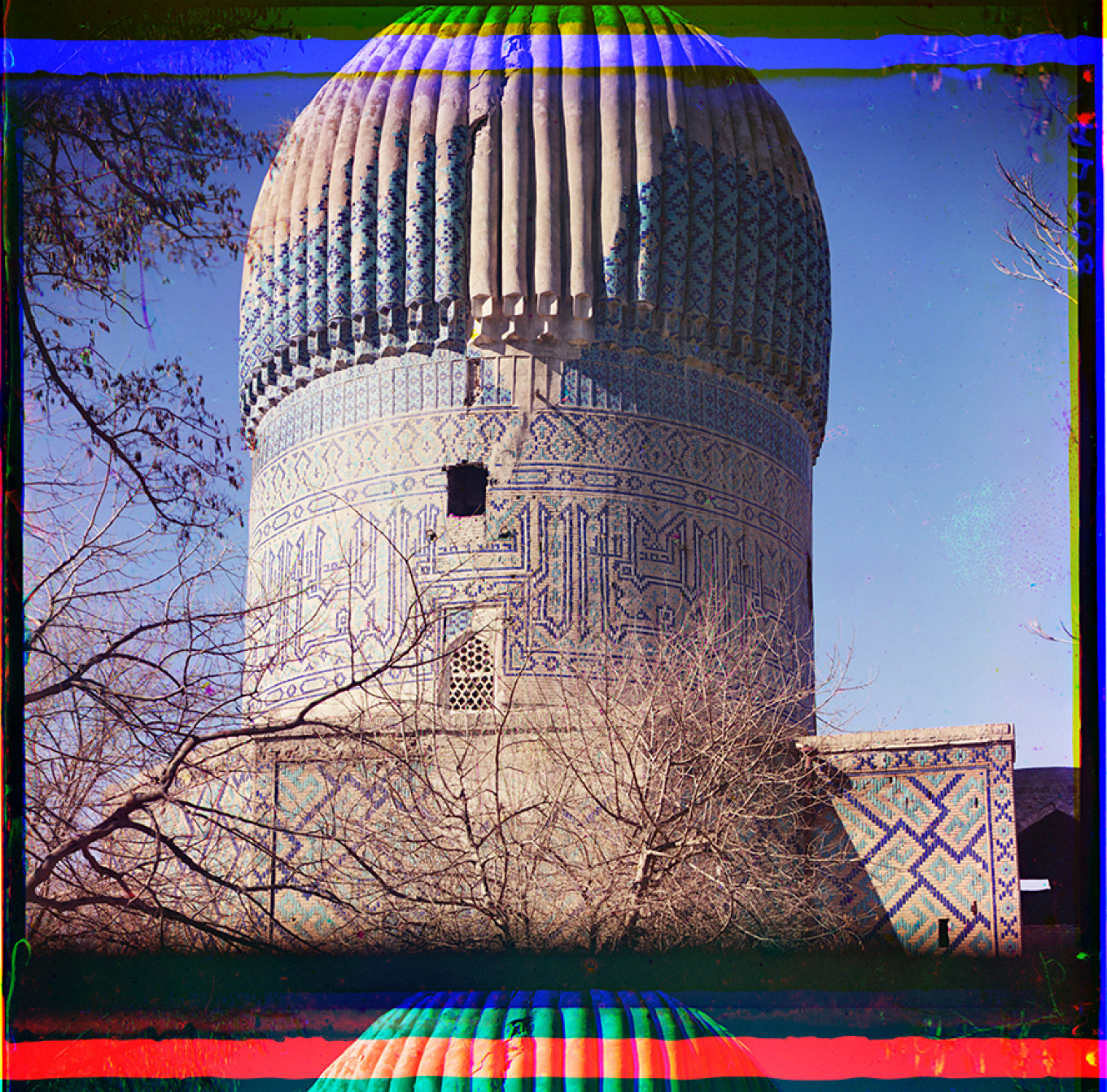

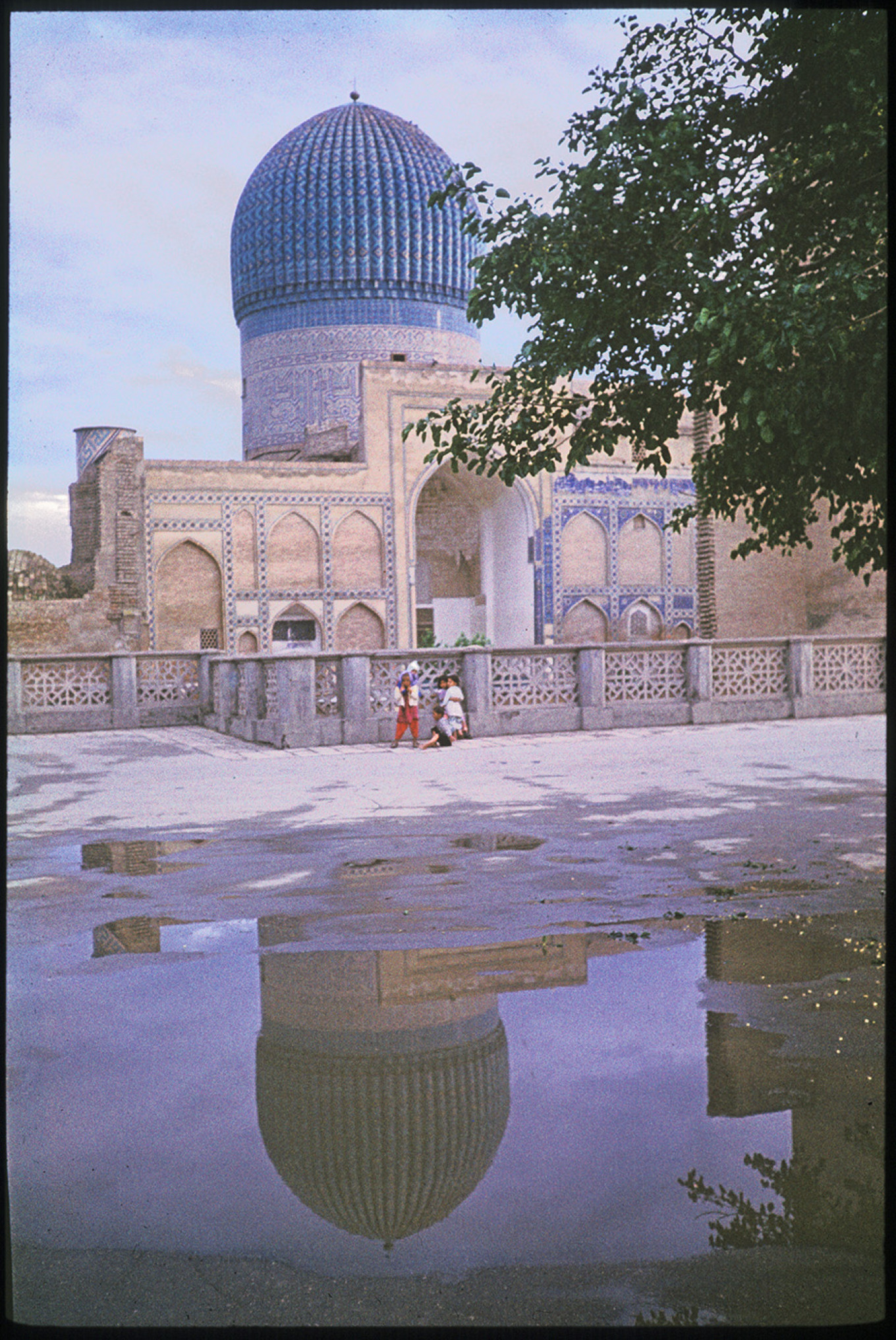

How fortunate we are, therefore, that much of the pioneering color photography of Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (1863-1944), who documented the Russian Empire in its waning decades, has survived for posterity. In his latest authoritative book, “Journeys Through the Russian Empire,” (Duke University Press, 2020) Russian scholar, photographer, and chronicler of Russian architecture William Craft Brumfield frames the life and work of Prokudin-Gorsky. He also puts his own magisterial career into sharp perspective with his own late 20th and early 21st-century photographs taken of some of the same subjects. The result is an extraordinary study of two photographers and, indeed, two Russias.

Prokudin-Gorsky was a creature of his expansive and creative era. This polymath, inventor, explorer, entrepreneur, and photographer was a scion of Russia’s provincial nobility. He received an excellent education in St. Petersburg that focused on both science and the arts, perfectly positioning him to pursue his passion for the emerging technology of photography. Prokudin-Gorsky felt strongly that photography demanded a full understanding of the science behind the technology, but he also understood its inevitable march towards main-stream use by amateurs; his ability to make peace with these competing notions was one of his greatest strengths, and a strong entrepreneurial streak enabled him to harness the economic potential of the emerging phenomenon in a ground-breaking career.

Prokudin-Gorsky studied in St. Petersburg, graduating in 1889 from the faculty of Natural Sciences, after which he traveled to both Berlin and Paris to work with leading chemists and photographers. From the beginning of his professional life, he pursued his goal to produce color photography, but throughout his career, he was a vocal champion for his colleagues, assuming the editorship of Russia’s “Amateur Photography” and campaigning successfully for photographers to assert ownership of their work.

The scope of Prokudin-Gorsky’s ambitions matched the size of the Russian empire he sought to capture and preserve with his new color technology: a daunting one fifth of the world’s land mass with a Byzantine imperial bureaucracy that hindered access to many of the empire’s more picturesque corners and subjects. Fortunately for Prokudin-Gorsky, in 1909 his work came to the attention of the imperial family — passionate shutterbugs themselves — and after successful presentations of his color slides to the tsar’s brother, Grand Duke Michael and his mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, Prokudin-Gorsky secured an invitation to present them to Nicholas II and his family.

Contemporary sources characterize Nicholas II as a great waffler, but in the matter of Prokudin-Gorsky’s request for imperial patronage of an ambitious plan to photograph the Russian empire, the sovereign acted swiftly and remained steadfast. Nicholas II ordered the minister of ways and communications to furnish Prokudin-Gorsky with a specially designed Pullman railway car for his laboratory and access to river transport. The tsar also gave Prokudin-Gorsky an enviable laissez-passer for the entire empire, and an order that enabled the photographer to solicit aid from all government officials. For the next six years, Prokudin-Gorsky traveled throughout the empire on several regional expeditions, using his color method to document the ministry’s development projects, particularly the rapidly expanding railroad network that was fast-forwarding Russia into a powerful industrial nation. But along the way, he also captured the natural beauty of Russia’s wilder corners: the majestic Caucasus, the arid desert of Central Asia, and the dense forests of the Urals.

Prokudin-Gorsky’s innovative color technology involved photographing a subject with three separate plates. By necessity, his subjects had to be stationary or at least be willing and able to stand very still. But the resulting images are anything but static; Prokudin-Gorsky’s show masterful framing and use of perspective in photographs that pulse with life and color.

It is unlikely that Prokudin-Gorsky understood that he was documenting a world that would soon disappear. But disappear it did. In 1918, Prokudin-Gorsky fled Russia, taking with him thousands of color slides, which he had tried to get the Stolypin government to purchase in 1910, but they had, as Brumfield notes, “with myopic parsimoniousness… let the matter die.” After Prokudin-Gorsky’s death in 1944, the Library of Congress acquired the collection of his negatives.

Fast forward half a century, and another photographer and chronicler of Russia’s rich architectural traditions began to document many of the same locations that first drew Prokudin-Gorsky. William Craft Brumfield is the foremost Western expert on Russian architecture and taught at some of the world’s most renowned centers of Slavic studies, including Harvard, Tulane, and the Pushkin Institute. In 2019, in recognition of Brumfield’s contribution to Russian culture, President Putin awarded him with Russia’s highest honor for a foreigner, the Order of Friendship.

Brumfield is an academic who thrives in the field — his outstanding photography of Russia’s architecture is an invaluable resource to students of Russian art and architecture, as well as the country’s history. He was a natural choice to curate a public exhibition of Prokudin-Gorsky’s collection for the Library of Congress in 1986 and his association with the library and the collection has continued to this day, with “Journeys Through the Russian Empire” as a magnificent culmination of this fruitful collaboration.

“Journeys Through the Russian Empire” presents a selection of photographs from eight of Prokudin-Gorsky’s expeditions throughout the Russian Empire, from 1909 to 1916. Brumfield has cleverly arranged these, not chronologically but in a logarithmic spiral like that of a nautilus shell, beginning with the oldest Russian principalities such as Suzdal in the center and expanding ever outwards to the Volga river lands, the Ural Mountains, Siberia, and Central Asia. The spiral culminates in a trip to the remote Solovetsky Islands, which in Prokudin-Gorsky’s day housed a monastery and in Brumfield’s — a decommissioned Gulag camp. Each chapter showcases selections of Prokudin-Gorsky’s work and Brumfield’s own photograph of the same subject, often from the same vantage. Occasionally, the shots are so uncannily similar that one has to refer to the notes to ascertain which image predates the other.

But in other evocative pairings we cannot help but note the effects not only of time but also politics and economics. Brumfield shows us churches that have repurposed or simply allowed to decay, but he also shows us more recent attempts to restore and revitalize. While Prokudin-Gorsky’s photos were taken over only seven years, Brumfield’s span almost three decades, and in this progression we see the changes in Russia from the Soviet era through perestroika to the present.

Anyone who has traveled throughout Russia’s vast regions recalls the staggering beauty of nature and the magnificence of the architecture, particularly in the more remote corners of the country. Both Prokudin-Gorsky and Brumfield capture this richness with images that are so immediate and evocative that one almost feels the heat of the sun radiating off the stone walls of Registan Square in Samarkand or catches sound of the Volga River lapping against the shore of tiny jewel-like Uglich or detects the musty odor of a long-neglected church. “Journeys Through the Russian Empire” deliberately eschews photos of either Moscow or St. Petersburg, allowing the quiet majesty of Russia’s often overlooked provinces to take center stage. This is an excellent decision by Brumfield, reflecting and honoring Prokudin-Gorsky’s desire to capture the breadth of Russia for the empire’s citizens.

“Journeys Through the Russian Empire” is a masterful achievement that readers will want to savor and return to again and again. In its pages are insightful lessons on everything from color photography to the nature of time. William Craft Brumfield has brought all of his considerable talent, expertise, and energy to produce an invaluable resource for students of Russian history, photography buffs, nature lovers, architecture aficionados, and anyone who longs to explore the expansive Russian empire through the eyes of two eminently talented and devoted photographers.

Excerpt from “Journeys Through the Russian Empire”

Above the Abyss: A Reflection on Photography as an Instrument of Memory

Time and memory are two of the broadest categories in human thought, fundamentals of philosophy, and of thought about thought. Interpretations of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographic project—now universally available through the digitization of his collection at the Library of Congress—have often focused on their technical brilliance and the nostalgic appeal of a lost world vividly rediscovered in brilliant color. These photographs transport us back in time and create an illusion of memory. The images seem so tactile and so close. Such interpretations and glosses on Prokudin-Gorsky’s work tell us much, but what do they neglect?

In Prokudin-Gorsky’s idealistic project, photography, like the railroads that he rode and documented, served as a means of uniting a vast, culturally diverse empire through a vision that would enlighten those who saw the images. To behold the regions of the empire in bright colors would be to comprehend not only its diversity but also the role the empire played in uniting the peoples of an immeasurable Eurasian territory. In addition to documenting the medley of diverse cultures, he also recorded evidence of the empire’s development. Commissioned to photograph the expansion of Russia’s transportation network—seen as the engine of economic growth and progress—Prokudin-Gorsky paradoxically used that network as a means of recovering Russia’s past. Yet his vibrant images portray an order that would collapse in almost unimaginable violence within a decade or less of the photographing. It would be unreasonable to fault Prokudin-Gorsky for lack of foresight, although as a resident of Saint Petersburg he was aware of the possibility of terror attacks: One of them killed a potential patron, prime minster Peter Stolypin, in 1911. And when he photographed Leo Tolstoy at his Yasnaya Polyana estate in 1908, he surely knew of the great writer’s fulminations against the imperial regime and the Orthodox Church.

Nonetheless, with the eventual patronage of Nicholas II, Prokudin-Gorsky embarked on a heroic enterprise to record the empire as none before him had done, an enterprise that continues to enrich our knowledge and vision decades later. The question is not what eluded his vision but how do we respond to that vision? What are the levels on which we can respond? These are by no means simple questions, and attempts to address them often have an ideological bent. “The Russia that we have lost”—who are “we” and what was “lost” after 1917?

The answers could well depend on the specific group considering the question. Among Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs of splendid Islamic monuments in Bukhara, there are portraits of haggard prisoners held under barbaric conditions. Some might argue that these portraits, together with those of ample local potentates, play into a European, orientalist narrative of Central Asian societies as semibarbaric. But such an interpretation is out of character for Prokudin-Gorsky and does not correspond to the direct humanity of his photographs. In any event few would regret the loss of the Emirate of Bukhara, a harshly repressive regime that at the time of Prokudin-Gorsky’s visit had the status of a Russian protectorate. But should we contemplate Prokudin-Gorsky’s specifically Russian photographs with-out an awareness of the other parts of the empire that was Russia?

A contemplation of the Prokudin-Gorsky photographs raises challenging questions of social and political history. Several of his photographs show Russian settlers and enterprises in the southern areas of the empire, but to whom had that land belonged? The perspective that Prokudin-Gorsky implicitly endorses in his photographs is that of Russians as bringers of progress and amelioration. This approach became especially pervasive after widespread peasant uprisings in 1905–6 that led to the “Stolypin reforms” of 1906. For the next half decade Peter Stolypin initiated policies for the re-settlement of hundreds of thousands of land-poor peasants from the Russian heartland to the empire’s peripheral areas—a process facilitated by railroad construction. Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs show evidence of this new Russian presence.

However, it was one thing when peasants were steered to uninhabited tracts in Siberia, and another when they were given plots in southern areas (particularly Turkestan) that were inhabited by non-Russian peoples. Already exposed to wealthy, extensively irrigated cotton estates (which Prokudin-Gorsky also photographed) in the Syr-Darya basin, significant elements of the non-Russia population harbored a festering resentment that contributed to the explosive Central Asian revolt of 1916. This uprising, exacerbated by wartime conscription of Muslims, spread through much of Turkestan (including the Samarkand region) in the latter half of 1916 and led to a staggering carnage that is referred to in contemporary Kyrgyzstan as “genocide.” Among other victims were Kazakhs and Russian settlers. The area that Prokudin-Gorsky had calmly photographed five years earlier was now torn by violence, while the photographer himself was at the other end of the empire at work on his last Russian expedition, to document construction of the strategic railroad to the new Arctic port of Murman (Murmansk). This urgent military project involved the forced labor of Central Powers prisoners-of-war, whom Prokudin-Gorsky also photographed.

The preceding comments should persuade us that nostalgic interpretations of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photography (“the Russia we have lost,” a sense of the lost idyll) may be superficially appealing, but they ignore a larger, at times devastating, context. We allow these photographs to transport us to reveries of the past, yet a knowledge of Russian history compels us to think about the future (now past) of the subjects portrayed. For example, to look at a group of children on a White Lake levee in Belozersk is to wonder what became of them in the next decade, after suffering years of war, social collapse, hunger, and savage violence. How many of them survived? The church in the background has long been a ruin, but what happened to the children?

The appealing, innocent faces of these and other children in Prokudin-Gorsky’s work remind us of the opening words of Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory: “The cradle rocks above the abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” Photography is “light writing,” and with an awareness of history Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs illuminate that Nabokovian moment. It might be added that Speak, Memory, first published as a single volume in 1951, is primarily devoted to a time and milieu that also nurtured Prokudin-Gorsky and was both forever lost and preserved through the writer’s memory.

Excerpted from “Journeys Through the Russian Empire: The Photographic Legacy of Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky,” by William Craft Brumfield. Reprinted by permission of Duke University Press. © 2020 Duke University Press. All rights reserved.

For more information about the book, author and Prokudin-Gorsky, see the publisher’s site or find more information here.