From the outside, it may seem that Moscow life hasn’t changed at all, but this is a false impression. To understand how people who remain in Russia feel, here are three poems, all written after February 2022. Their authors describe what they see around them, and also what it’s like to write poetry in Russian today.

The impetus for writing these three texts was almost the same emotion: the horror at having to be an unwilling witness to horror. But each author reflects on this state in their own way.

Maria Lobanova describes one brief moment in her life that captures the shock of seeing photographs of a murdered child. It’s the moment of of encountering the impossible, a state of absolute inner turmoil: “I don’t know what I feel right now” says the heroine of the poem.

German Lukomnikov describes how the literary activity of his collective persona develops against the backdrop of the events of recent years. Although in the text there are some emotions — astonishment, fear — the author speaks of them with detachment, analytically, simply stating facts.

The poetry of Luba Makarevskaya, to the contrary, is very intimate, focused on the study and meticulous dissection of her inner experiences. Her heroine knows very well what she is feeling; she lets the catastrophe pass through her own body, which all turns into a “note of unbearable regret.”

Maria Lobanova

***

By education and profession Maria Lobanova is a lawyer who began to write poetry only recently, in 2019. Her debut book “Drilbu” was published in 2023 in the new independent poetry series “Paroles,” which lists resistance to “repressive reality” as one of its tasks.

***

летняя субботняя Москва

мамы гуляют с колясками

такими же, очень похожими

на ту

вокруг зелень и только прошёл тёплый летний дождь

у меня нет детей

недавно хотела удочерить новорожденную малышку

обговаривала с мамой возможности кормления

размышляла о родительстве

это было за неделю до коляски

и разорванного тельца

не знаю, что чувствую сейчас

словно возвращается смертная казнь в рай

и ангелы готовят электрический стул

специальный блок для расстрелов

начищают стволы

учат псалтырь

***

summer Saturday Moscow

moms strolling with prams

the same ones, or very similar

to that one

It is green all around and a warm summer rain just passed

I have no kids

lately I wanted to adopt a newborn baby girl

talked through feeding options with my mom

thought about parenthood

that was a week before the pram

and the torn apart tiny body

I don’t know what I feel right now

as if the death penalty comes back to paradise

and angels are preparing the electric chair

a special room for firing squads

clean the guns

learn the Psalms

Translated by Katia Szarek for ROAR.

Maria Lobanova:

About a year ago, I was driving and turning from Marshal Zhukov Avenue onto Zhivopisnaya. I stopped at a traffic light: the sun was shining, it had just rained, and I saw these happy mothers with their children walking around Moscow… But the thought of that stroller and the tiny torn body* didn’t leave my mind. I felt a strong sense of the time and its utter madness, when you have a torn baby’s body inside you, but life outside seems to go on as usual. The pain from this gap was so intense that I decided to write about it.

But the text is not to say that normal behavior, like walking with a child, is now something bad. I don’t like it when someone explains to someone else that their reaction is wrong — this approach is inherently flawed. We don’t know what’s going on in the minds of other people, what they feel — perhaps normalizing their life helps them to cope, we don’t know if they will have PTSD or not. It’s incredibly naive to assume that people in Russia are insensitive. We have criminal prosecution for simply saying something. The problem is that people don’t trust each other and remain silent, not that Moscow is flourishing and the picture hasn’t changed.

“Angels clean the guns” — even the kindest, most loving people in the world sometimes can’t bear it as they read the news and see what’s happening. They are even ready to get angry, to allow a parade of rage inside. Sometimes they are even ready to pick a weapon because they can’t bear to look at it, live with it. I myself don’t “clean the guns,” of course. Every living thing will eventually die, and this makes me feel great sadness for everyone, even for not very good people. When I realize this finiteness, I automatically sympathize. I think the reason we are still alive and can still talk and support each other is precisely this mechanism that keeps us from giving free rein to our own rage, that allows us to look at the world without a blinding veil of hatred.

The most constant feeling is a sense of helplessness, some terrible disappointment — how we could have missed such monstrous perspectives in our own existence that are now obvious.

I have never stopped writing. There was a period when I couldn’t do it simply from shock — until mid-March 2022, that is, for about two weeks. But for me, when you can’t write anything at all, not even a line — that’s a lot.

It is important that the text is written. Sometimes this writing is an act of courage, an act of bravery. This bravery is not in the face of censorship and some external circumstances, but in the face of your own limited mind. Working with language and your own dark side is the hardest part. And then the authorities come and say: “I won’t let you publish this” — sometimes, as we know from experience, this is even to the benefit of the texts. The 20th century teaches us that you can continue writing — it’s possible to preserve the inner strength that gives you the courage to write freely.

But I don’t know what I would say if I were to face criminal charges or if I were already in jail. I was just watching the story of Yelena Milashina** and imagining with fear how they would start breaking my fingers if I didn’t give them the PIN code to my phone. Right now I’m writing under my own name, but maybe someday I’ll change my position and write under a pseudonym. Because everything changes and I don’t know what tomorrow will bring.

* On July 14, 2022, as a result of rocket shelling in the city of Vinnytsia, more than two dozen people were killed, including three children. The death of four-year-old Lisa with Down syndrome, who died in front of her mother, made a particularly powerful impression. The horrific photos of the overturned pink stroller circulated around the world.

** Yelena Milashina is a well-known reporter with “Novaya Gazeta” who was recently beaten in Chechnya when she went there to write about another political trial.

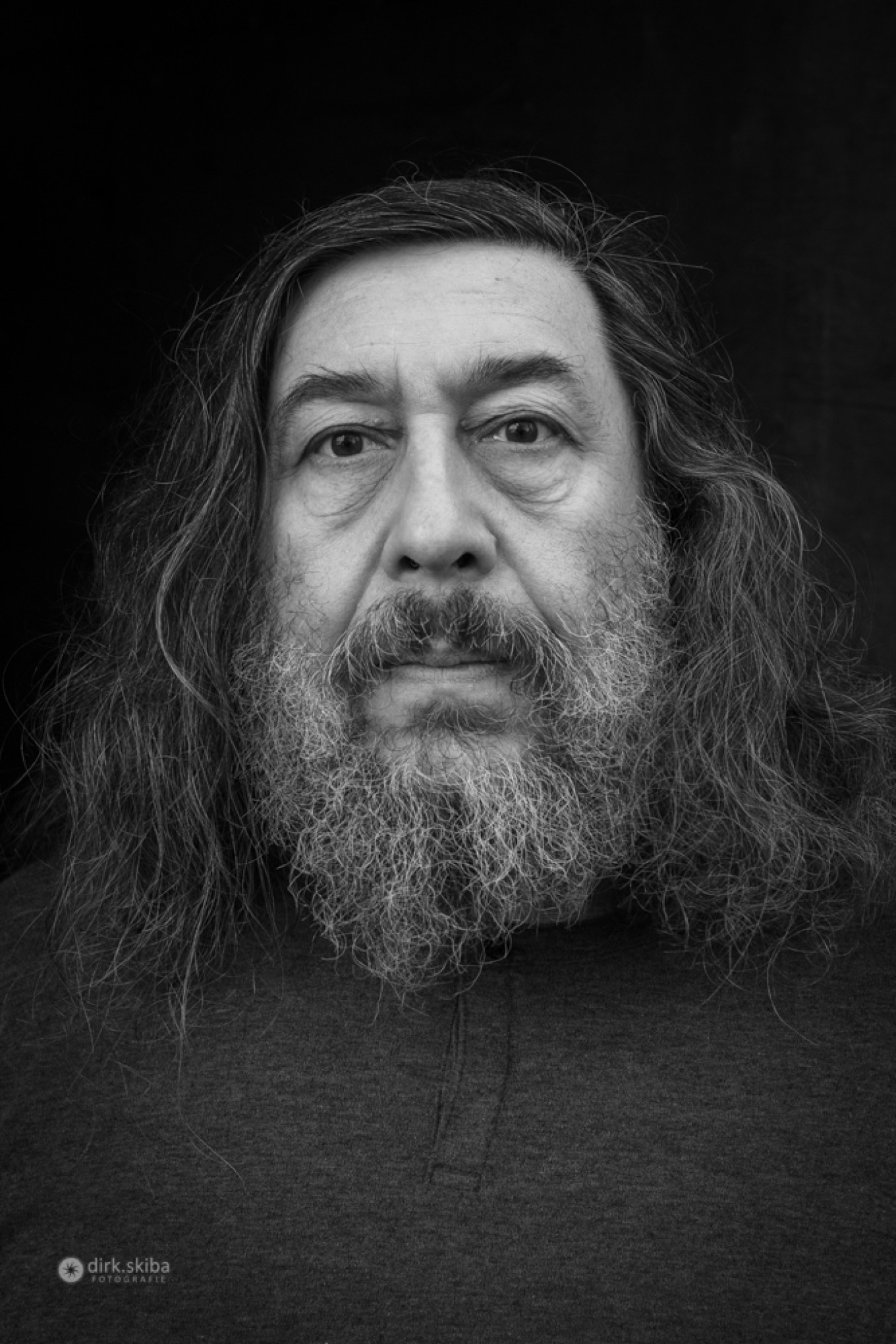

German Lukomnikov

***

German Lukomnikov has been a part of the literary scene since the 1990s and is well known as a master of minimalism, palindrome, and combinatorial poetry. Lukomnikov’s texts always teeter on the edge of seriousness and light, non-committal language play, but his voice has become one of the few to reflect accurately and fully the range of complex experiences of a person living in Russia today.

***

Как же так

Твоих друзей

Сажают

Мучают

Убивают

Начинается война

А ты

Сам в постоянном ожиданье

То ли ареста

То ли бомбы

Переводишь Гамлета

Или Божественную комедию

Или составляешь

Этимологический словарь русского языка

И может быть даже

Получаешь за это

Премию тирана

Гордясь что промолчал когда все выкрикивали приветствие

Да

Так как-то вот

***

How can it be

That your friends

Are jailed

Tortured

Murdered

That a war begins

And you too

Expect every minute

An arrest

Or a bomb

But keep translating Hamlet

Or the Divine Comedy

Or compiling

An etymological dictionary of the Russian language

And perhaps

You even receive

A prize from the tyrant

Priding yourself on keeping quiet when everybody hailed him

Yeah

Just, y’know, like that

Translated by Dmitry Manin for “Disbelief.”

German Lukomnikov:

In my more typical poems, rhyme or puns are very important. My free verses are usually very short, just a few words — fleeting observations on language, the world and myself. And if I suddenly make the whole twenty lines without rhyme, it’s probably an attempt at direct speech, a scream, a cry from the heart.

This poem is one of the very first ones I could write after the war started. For the first few weeks, it seemed to me that I would never write anything again. And I didn’t immediately post it online; there was a feeling that any writing was completely pointless… The one thing that supported me at the time was when I finally posted this and my other first poems, there were many grateful responses, including some from my Ukrainian friends. And after my new poetry was published in Volga magazine in January this year, I received so much support from hundreds, if not thousands of readers, that I was finally convinced: “there is someone who needs it.”*

Of course, it’s terrifying to write all this, terrifying to publish. Zhenya Berkovich and Svetlana Petrychuk** are in prison, they took Seva Lisovsky*** away and frightened him terribly… I had a vision: I’m walking down the street and see a monument being unveiled. I looked more closely and realize that it’s a monument to me. People are speaking and praising me and my poetry, people are reciting my verses. And at the very moment, several police officers grab me and drag me into a car. The last thing I see is the date of my death appearing near the date of my birth on the pedestal. It’s truly a strange feeling, and my reality is very strange. People write theses on my poetry; last year my texts were released as an album in the Pushkin Museum; just recently I triumphed in the Mayakovsky poetry slam and at the same time I live in constant fear, like in a horror movie.

I haven’t yet translated “Hamlet” or “The Divine Comedy,” and I didn’t work on an etymological dictionary. These are allusions to Pasternak, Lozinsky and the linguist Vasmer. Boris Pasternak translated “Hamlet” in the late 1930s-early 1940s. He started the translation because Meyerhold asked him to do it for his theater, and while he was in the heat of translating it, Meyerhold was arrested and then shot. “And perhaps/You even receive/A prize from the tyrant” is about Mikhail Lozinsky, who was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1946 for his translation of “The Divine Comedy.” Lozinsky, who was a friend of the executed poet Nikolai Gumilyov, the friend of Osip Mandelstam, who was tortured in the Gulag, and who was repeatedly arrested himself.

Max Vasmer was a German linguist who was born in Russia but lived in Germany from the 1920s. During the war, he compiled an etymological dictionary of the Russian language, and in 1944, a bomb hit his apartment in Berlin. He was in a bomb shelter at the time, but his giant card file was destroyed. He started over and still managed to compile the dictionary, which now is used by everyone who learns the etymology of Russian words.

I read that when he went to work at the Berlin University, he carried two briefcases with him to avoid giving the Nazi salute at the entrance. “Priding yourself on keeping quiet when everybody hailed him” is about that. It’s about what we should one do in the special circumstances we’ve found ourselves in now. Should we continue doing our work as if nothing has happened? Is it true that not shouting greetings to an unrighteous authority is already an act of heroism? Well, it’s… well, it’s a question. There’s no statement in this poem, just questions and an understanding that things we thought were completely impossible, unimaginable, something you only read about and saw in movies — this happened, it happened to all of us.”

* A very well-known quote from the famous poem of Vladimir Mayakovsky “Listen!”: “If stars are lit it means – there is someone who needs it” (in the translation of Dorian Rottenberg)

** Theater director Evgenia Berkovich and writer Svetlana Petrychuk are accused of justifying terrorism in a play about women who run to Syria to marry radical Islamists. Berkovich is also well known for her anti-war poetry.

*** The theater director Vsevolod Lisovsky was arrested right in the middle of his anti-fascist show based on “Fear and Misery of the Third Reich” by Bertolt Brecht. Now Lisovsky is outside Russia.

Luba Makarevskaya

Luba Makarevskaya writes both poetry and prose. In 2022 she published two books at once: a collection of poems “One More Experience of Radiance” and a collection of short stories entitled “The Third Stage.” Her recurring theme — a straightforward conversation about depression and corporeality — finds particularly poignant interpretation in contemporary realities.

***

Вырезать

как аппендикс

страну

и память о ней

Бледный след

на нашей коже

вечный синяк

принадлежность

Не задушишь

не убьешь

ломкое в голосе

будто я сама

Та самая

нота

невыносимого

сожаления

Не потому что

жаль

а потому что

было всегда

Как морозная

комната

и клейкая лента

вместо слов

Жестокость

разделившая

нас

на кровь

и слезы

Обратившая

зрение

в одно сплошное

свидетельство.

***

To cut out

the country

and its memory

like an infected

appendix

A pale

scar

a permanent

bruise

inescapable tie

Unbreakable

indestructible

my voice breaks

as though

I am

That

note of

unbearable

sorrow

Not for the loss

but because

it was always

so

Any words

stopped

as though with duct tape

in a freezing house

A cruelty

which has divided

us

into blood

and tears

Which has turned our sight

into a constant

continuous

witness.

Translated by Dmitry Bosky for ROAR.

Luba Makarevskaya:

I wrote this text on October 5, soon after the mobilization was announced. Everyone left — I didn’t know what would happen to my life, whether I would see my love and other people dear to me again. I went through a severe depressive episode, which I later described in many texts — in short stories and in a cycle of poems.

“To cut out the country like an appendix” is perhaps also an attempt to try on emigrant’s status, but it’s more about how to relate to the country you live in. How to respond to it and protect your safety, consciousness and inner life in this reality, regardless of geographic location.

After February 24, for the first six months or so I had a difficult relationship with writing. You’d think: Oh, my God, I’m using the language used to deliver those terrible military orders. You feel a disconnect with the language, and that’s a very difficult experience for a writer. Then you still try to make it yours, but no longer as a field of violence, but as your own tool, your own way of interacting with the world, setting the language free from the captivity of violence. However, even now, I feel that my language is maybe not as free as I would like it to be, that in the pre-war situation it was more vivid, rich. Now it feels as if a latch has locked some door and there is a distance between me and that language. I am ashamed to write texts that are too beautiful and strive for my words to be drier, more ascetic.

The feeling of guilt has been replaced by a sense of being a hostage to the situation. This this is the all-encompassing experience. I published short story about it called “Captain White Snow.”

There is also a lasting feeling of humiliation. It’s humiliating to realize your life doesn’t fully belong to you. Today it’s mobilization, tomorrow — something else, you never know what else they will do to you and your loved ones.

The final lines of the poem describe the trauma of witnessing, since the whole society — at least the thinking part of it — has been experiencing this trauma. You feel acute fear, but you can’t do anything, and you are forced to just watch the violence. And you think: Oh, God, can I live after this? But the state of mourning is never permanent. I am often asked, “How can it be that you describe depression but you are so active?” But internal pain doesn’t necessarily manifest itself as sitting in a dark room. Sometimes this conversation reminds me of a rape victim who is asked why she is using makeup and why she is smiling. Well, because she’s still alive. Each of us who is alive and chooses to live has no choice but to live.

Recently I reread Akhmatova’s “Requiem,”* and of course I cried, because it seems like she wrote it today. Russian Fin de siècle has unexpectedly become very relevant. In my 20s I loved the Beatniks and laughed at Fin de siècle, but now I’m in constant dialogue with these texts. I would like to make this clear: my poem is not only about what is happening right now. And the sight that has turned into “a constant continuous witness” — this is not my personal sight, but a collective sight.

*A famous poem by Anna Akhmatova, written during the repressions. She started it in 1934-1935 when her common-law husband Nikolai Punin was arrested along with her son, Lev Gumilyov (his father, Nikolai Gumilyov, had been executed in 1921).