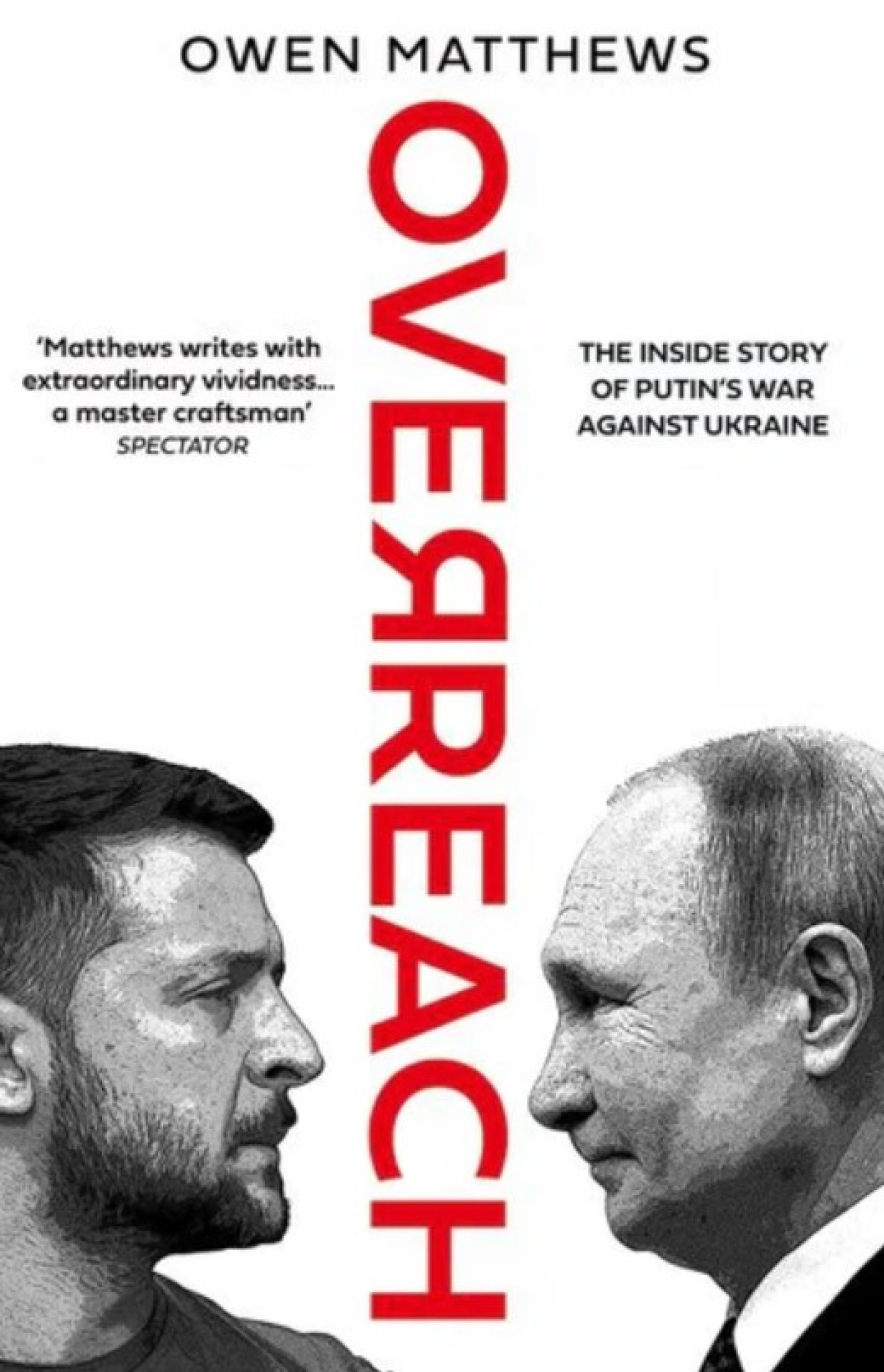

Last week Owen Matthews won the 2023 Pushkin House Book Prize for his book, “Overreach: The Inside Story of Putin’s War Against Ukraine,” called “an impressive achievement: a work of accessible history, with very vivid writing, depth and historical sweep” by Yekaterina Schulmann, the chair of the judges. The Moscow Times talked the Matthews about the prize, why he wrote the book, and a few things he really wants us to understand about Putin, Russia and this war.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Moscow Times: Is this the first major book prize you’ve won?

Owen Matthews: I’ve been shortlisted for dozens and dozens of awards. Never won one. The Guardian First Books award. Didn’t get it. The Pushkin House Prize, twice before. Didn’t get it. The Orwell Prize, didn’t get it. The Medici Prize in France. They’re endless, my failures. Yes, this is the first time I’ve had a prize since I was nine.

It’s a great honor. The whole point about what makes any of book writing really worthwhile is to win the respect of the people whom one respects oneself. Donald Rayfield, the great Chekov scholar, wrote that my book was, “A classic as enduring as Orwell’s ‘Homage to Castle Catalonia’… I’ll take that.

TMT: Why did you want to write about the origins of the war?

OM: This war is unusual insofar as it’s literally all happening inside the Kremlin. Ukraine doesn’t hold the answer to why this war happened. It’s not really about Ukraine, it’s about the particular psychodrama inside the mind of Vladimir Putin and also inside the Kremlin in the months and years leading up to the outbreak of the conflict… and the ideological shift that occurred inside the Russian elite that allowed this disaster to happen.

I realized that actually slightly to my own surprise, I found myself remarkably well-connected, and to people who actually had something to say.

MT: What do you want people to understand?

OM: I would say four things. The first is that lots of the interpretations of Putin and the sort of standard off-the-shelf demonization of Putin may not necessarily be wrong, but they’re all more complicated. For instance, Putin as an imperialist. Well, that’s not entirely the picture. He’s not invading Ukraine. What he thinks he’s doing is saving people whom he regards as Russians, and hence the idea of asylum. So that’s really ethno-nationalism. It’s not imperialism, which sounds like an international relations sort of fine distinction, but actually it’s quite important to understand how Putin’s mind works.

The second thing is that the poisoned roots of the conflict are much more complicated than a simple imperial-colonial relationship. While it clearly it is a colonial relationship, it’s also a kind of familial relationship…. in that sense, the history of Russia and Ukraine is not the history of England and India. It’s like the history of England and Scotland. And you have interchangeable elites. In fact, Ukrainians have formed a remarkably large number of leaders, especially Soviet, and Ukraine had a Russian-speaking elite. And on the other hand, you had this upswell of romantic nationalism.

I think it helps to understand how complicated and challenging that legacy of Russian Ukrainian relations are, not just on a state level, but on a personal level for almost every Russian family.

The third thing is the extent to which the decision was not based on some kind of mania or craziness on behalf of Putin. It was just based on unbelievably bad information. He’s not irrational. He thought that the future would be the past. He thought that the Europeans would be as cynical as they had been with Georgia or as they were in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea. They would turn a blind eye. He thought that because the Russian army had defeated the Ukrainian army in 2000, in August of 2014 or in July 2015, then it would happen again.

He was assured that the Ukrainian elite was all bought and paid for. He thought he started the war for the same reason anyone starts a war: because he thought that he could win it easily. He overestimated his own capabilities, underestimated his opponents. It’s not an irrational sort of rage.

And the fourth and final thing is the mechanisms of propaganda in Russia. There are two parties actively participating in the propaganda, the creators of propaganda and the people who are propagandizing themselves. They want to believe.

They have a belief in the various myths that are sustaining the war — NATO was going to attack us. Kyiv was run by fascists. All these things which are palpably non-factual. It’s just not true. Nonetheless, Russians believe it, not because they’ve been bamboozled. They believe it because they choose to believe it. And the consequences of that reality are actually really enormously important if you’re talking about any kind of political revolution or upheaval in Russia.

They are actually involved and deluding themselves, but also, no less importantly, like many people all over the world, they care primarily about their homes, their families, their paychecks and so on. They’re uninterested in politics. And that sort of social order that’s pertaining for at least two decades in Russia is really incredibly hard to break.

So the collapse of the regime in Russia could actually be extremely dangerous — not just for Ukraine but for the world. But fortunately or unfortunately, I think there’s a surprising amount of resilience in the Putin system still. I don’t think it’s by any means on the verge of collapse. And I think we’re going to be living with this system for some time.

For more information about the author and this book, see the publisher’s site here. It can be ordered online here in the U.S. and here in the U.K.

“Overreach won for this year’s Pushkin House Book Prize, which was awarded on June 15 in London.