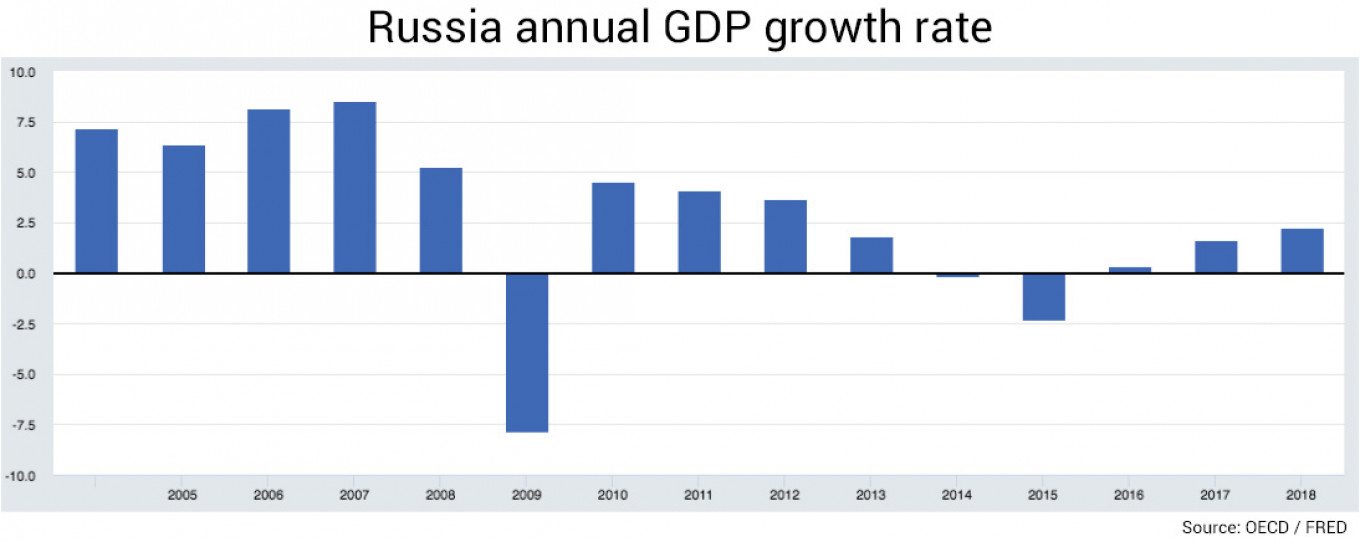

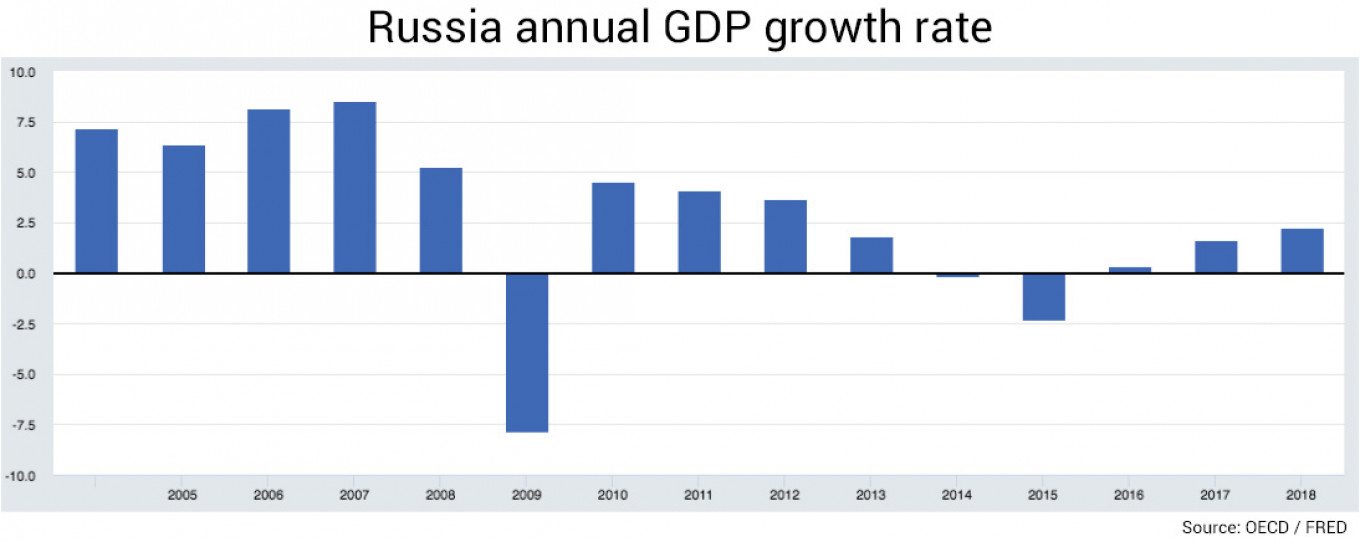

How do you achieve fast growth, without compromising macroeconomic stability? That is the central dilemma which has faced Russian policymakers since 2014.

When it came to making a choice between the two, stability won out nearly every time. Following the annexation of Crimea, provision of support for pro-Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine and interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, Russia pulled itself — and others pushed it — away from the international economy.

“Russia has created a model where it has a very closed economic system, but also a system that cannot generate growth. You can have stability or growth — and Russia has chosen stability,” said Saxo Bank’s chief economist Steen Jakobson.

As a new decade starts, however, Russia believes it has found a way to achieve both.

It plans to use the government war-chest built up through half a decade of ultra-conservative macroeconomic policy to kick-start a new growth chapter and boost living standards, all while keeping the economy safe from economic storms. Doing so will be no small feat.

2020: Fresh Start

“The previous five-to-seven years of a conservative policy mix was not an easy time for economic growth,” said Sofya Donets, economist at Renaissance Capital. “But it prepared a perfect starting point — almost a textbook case — for a nice fresh start.”

At the cost of faster growth, Russia now boasts what Elliott Auckland, chief economist of the International Investment Bank (IIB) calls “an incredible balance sheet”: a sovereign wealth fund of more than $125 billion, a government budget surplus that hit almost 3% of GDP in 2018 and net public debt of zero.

Russia also has stable and relatively low inflation, a sustainable banking sector and a free-floating exchange rate that leaves the ruble less dependent on oil prices than before.

Hopes for capitalizing on this position rest squarely on how the government will choose to use those impressive resources. Of the dozen analysts spoken to by The Moscow Times, government spending — how much, when and on what — was almost the only factor they cited that has a realistic chance of delivering faster economic growth in 2020.

“Russia could do so much more. The problem is the policy mix of the government has been super-conservative,” said Auckland. “If you look at the shift in policies that have occurred over the past year, with the National Projects and the Central Bank cutting rates, they are now becoming a bit more expansionary.”

Officially, the government plans to spend 19.5 trillion rubles ($310 billion) in 2020 — a 6.5% nominal increase compared to 2019. That includes allocations under Russia’s flagship six-year $400 billion National Projects which will step-up in 2020. Alongside that, Russia is also set to experiment with how to open the purse-strings of its $125 billion national wealth fund (NWF), and start investing future oil profits in the economy, now that the government is close to its desired safety buffer of 7% of GDP.

The Central Bank, too, will do its part, cutting interest rates toward 5% by the end of the year, economists forecast, in a bid to stimulate borrowing.

Conservatism reigns

Even with this extra stimulus, the growth pick-up is predicted to remain underwhelming.

The World Bank forecasts an expansion of 1.6% next year, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has pencilled in 1.9%. Even optimistic predictions, such as the IIB’s 2.5% “only sound good when compared to recent levels,” said Auckland, adding that the Russian economy should be aiming for a lot more.

“In relative terms, there is not too much to be proud of,” said Ekaterina Trofimova, a partner at Deloitte CIS. “Technically, this is not stagnation or recession, [but] in relative terms, Russia is in recession: We keep losing our very small portion of the global GDP pie.”

Some are also unconvinced by Russia’s commitment to its new-found free-spending mantra.

Looking over the government’s proposed budget for the next few years, ING’s chief economist Dmitry Dolgin wrote in a research note: “We interpret this as more of a verbal response to growth concerns rather than an actual willingness to sacrifice accumulated macro stability in favor of a short-term boost to the economy.”

The hesitancy for more adventurous spending plans may stem from the man ultimately pulling the strings.

“Putin prefers a very conservative approach to spending and wants to keep a comfortable budget and financial reserve cushion,” said Chris Weafer, head of consultancy Macro Advisory.

As he enters his 21st year at the helm of the Russian state, there is little evidence Putin might be willing to fully embrace a new economic agenda and risk what he sees as Russia’s progress toward economic sovereignty. He has repeatedly shown a fondness for reserve-building and a fear of going too deep into the red — for instance, by making paying-off Russia’s IMF debt one of his first priorities upon entering the Kremlin.

In addition, the latest developments in the debate over whether — and how — the government should start to spend its NWF also question whether the state is ready to shake its preference for saving.

On current oil prices, Russia could have up to 10 trillion rubles ($157 billion) in extra oil profits to invest over the next three years — a prize Russian businesses had been eyeing up.

“They will not get anywhere close to that,” said Deloitte’s Trofimova. “New requirements for the distribution of this fund are such that … very few companies will qualify. You certainly won’t see these trillions of rubles being used.” Recent proposals given a green light by prime minister Dmitry Medvedev would cap the total investment at one — not 10 — trillion rubles ($15.7 billion) over the next three years.

How to spend it

Then there’s the question of whether the Russian government has the ability to actually spend more, even if it wanted to.

After years of under-spending, Russia has a trillion ruble investment backlog, ING’s Dolgin calculates — something that will “test whether the institutional, administrative and legal framework [will] allow [the government] to power through large state-funded capital projects.”

“The National Projects are a great idea, and they’ve been funded, but actually implementing them is a very different story,” said Steen Jakobsen, chief economist at Saxo Bank. Official data shows most of the program’s spending tracks are already behind schedule.

“It’s not a lack of resources, it’s really the willingness,” said Apurva Sanghi, lead Russia economist at the World Bank.

“Our state officials are concerned about distributing cash,” said Trefimova. “Just imagine yourself in the position of somebody who signs papers … you would prefer to be blamed for inefficiency, instead of going to jail if an investment goes bad. That is why I’m not really optimistic that government spending can improve investment that much.”

However, in 2020, the pressure to spend is set to escalate, economists say — something which could help bureaucrats resolve their stubborn under-fulfillment problem.

“Domestically in 2020 the main challenge for the President and the government will be socio-economic,” said economist Vladimir Miklashevsky. “Russian consumers’ discontent with the current economic policies and GDP growth of under 2% may cause more open public disagreements. Thus, the government may intensify its infrastructure spending.”

“As we head toward mid-term, the president will increasingly pressure the government to improve economic performance and especially to grow household incomes,” Macro Advisory’s Weafer said. “That’s because the president is expected to focus more on political succession in the second half of his term and, to be able to do that, the economy needs to be improving.”

Another factor is Russia’s next parliamentary elections, scheduled for 2021, the IIB’s Auckland said. “I expect from 2020 we’ll already start to see a pick-up in spending.”

“The government has a lot of ways to stimulate the economy,” he added. “Even if it goes back on the National Projects it … can raise pensions or public sector salaries.” Auckland also expects the strict terms and conditions over how future oil profits are invested to be relaxed as the government gears up to full-time electioneering, and the recent increase in VAT could also be reversed in a bid to convincingly end Russia’s five-year living standards squeeze.

Geopolitical opportunities

Up against increased domestic pressure, however, Russia may be cautious about sacrificing its hard-won stability in the face of global economic and geopolitical headwinds.

Despite the rhetoric, “Russia is still a very open economy … it will not be able to escape any global downturn,” said the IMF’s Annette Kyobe. And with energy pipelines to Germany, southeastern Europe and China coming online in 2020, Russia is set to become even more integrated in the global energy economy — and vulnerable to fluctuations in demand for oil and gas.

Then, there is the great unknown for 2020: the U.S. Presidential Election. Russia is likely to feature prominently in the campaign, and analysts expect Moscow to continue its de-dollarization drive as congressmen and candidates clamour to appear tough on the Kremlin by threatening new financial sanctions.

“Russia could become a little more protected,” said Eurasia Group’s Jason Bush. “But the idea that it can protect itself from serious sanctions is massively over-blown. It’s like if you have 1,000 nuclear warheads being fired at you, and you manage to shoot half of them down — it’s not that much help.”

Toward a new growth model

In the face of such competing tensions both at home and abroad, the Russian dilemma — craving stability but lusting after growth — is not going to be resolved in 2020, the World Bank’s Apurva Sanghi said.

Analysts expect higher government spending to boost the economy — but not by much — and doubt the extent to which Putin can completely u-turn on six years of conservative economic policy.

But with domestic pressure intensifying, a balance sheet growing heavier every day and the idea of a post-Putin Russia coming into sharper focus, 2020 could be an important experiment in how Russia tries to tip the balance towards growth.

“We are at a crossroads where things need to change, because you cannot have 3.5% growth in an isolated economy. It doesn’t work like that,” said Saxo Bank’s Jakobsen. “With low growth, it’s not unlikely that Russia could have a recession in 2020. Maybe change comes from this lack of change.”

“Russia can reach 3.5%, but only in a more open model. It went for stability for some very good reasons. But the time is now up for renewing the model.”