One hot day in August an older gentleman in rather poor health decides to celebrate the fine weather with a walk through his favorite forest on the outskirts of a European city. Tired from his walk, he wends his way to a small town, past a soaring old cathedral to an outdoor restaurant in the village square. Here the waiters treat him no differently than the other pensioners, and it would never occur to any of them that under the plastic surgery, contact lenses, and a carefully maintained accent is a former Soviet intelligence officer who defected more than 30 years ago.

He orders beer and a steak. While he waits for his meal, he sips his beer and bats away the wasps that are drawn to the sweet hoppy beverage. Suddenly he feels the sting of a wasp on his neck. As he collapses, he recalls a man who walked past him just as he was stung. Before he slips into oblivion, he manages to whisper that he was poisoned.

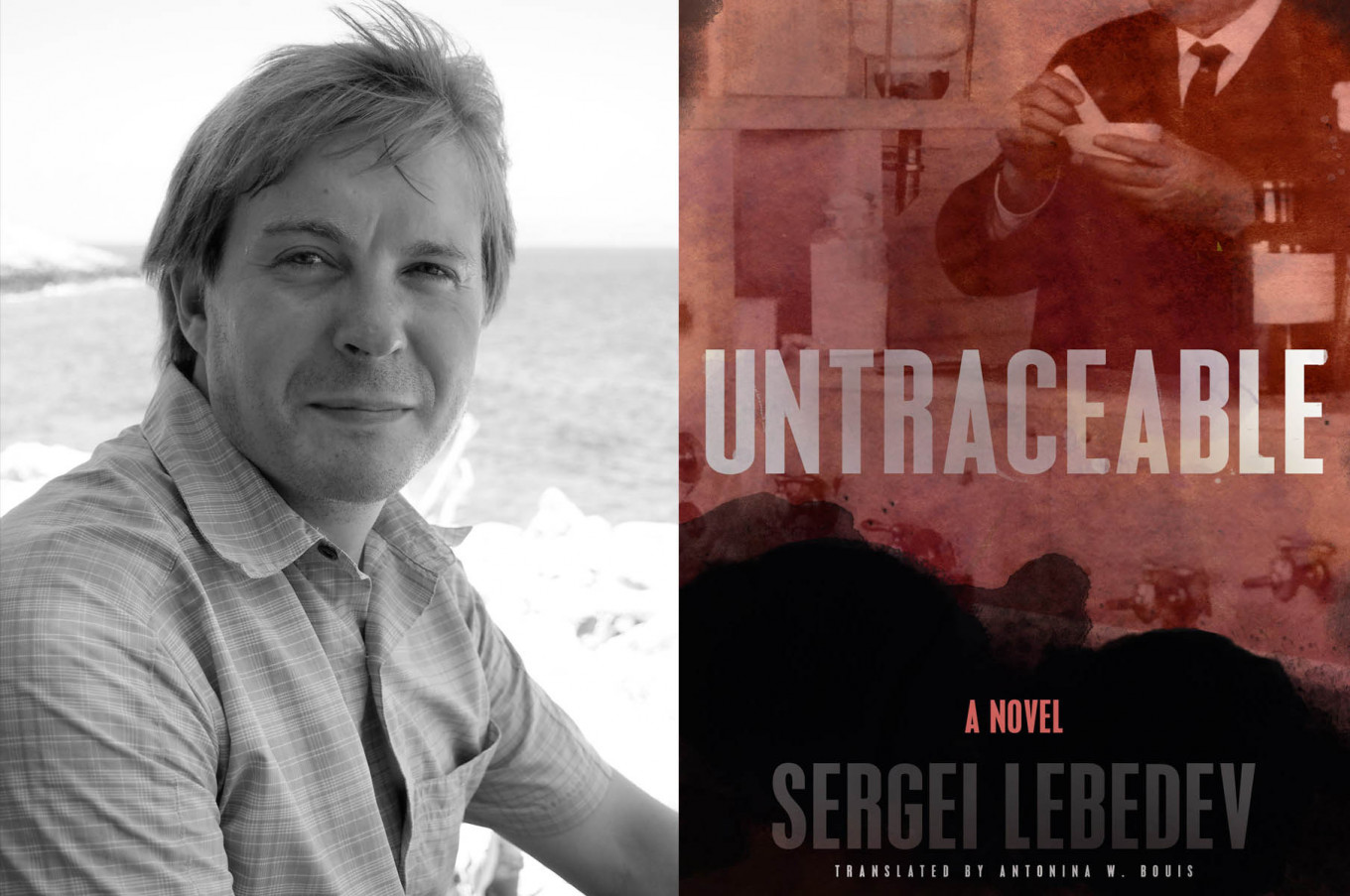

So begins Sergei Lebedev’s new novel, “Untraceable,” translated by Antonina W. Bouis and published by New Vessel Press.

The incident that begins the novel is the catalyst that sets in motion the rest of the story. Another old man, also a defector, also in poor health, is asked by his Western handlers to consult on the case of the man who was poisoned. For good reason: the defector is the scientist who invented the poison that killed him.

In Moscow, two generals in a safe room look over intelligence reports and conclude that the consultant is Kalitin, the creator of the chemical weapon Neophyte. They send a two-man team to assassinate him with that chemical. The novel traces the path of Kalitin as he agrees to collaborate with the state on the creation and testing of these weapons, and the path that leads the two men to be sent as his assassins.

In an interview with The Moscow Times, Levedev said that the idea for the novel did not come from the fact of the 2018 attack on the defector Sergei Skripal in Salisbury. It came from a place name Lebedev noticed in his reading about the case. Novichok was developed in Shakhany, a closed military site founded in 1927 as a secret chemical weapon research and testing facility used jointly by the German and Soviet armies.

“The German specialists who had invented chemical weaponry almost a decade before couldn’t continue their development in Germany because of the Treaty of Versailles, so they came here,” Lebedev told The Moscow Times. “And Salisbury, where the poisoning took place, happens to be near Porton Down, which the English founded in 1915 to respond to that German threat of chemical weapons. The specialists from Porton Down were the first responders who quickly identified the chemical agent.”

“In that story,” he said, “The beginning and end came together. Novichok was something new, but it had a long shadow to the past.”

Lebedev’s previous novels walk among the shadows of Russian history: the Gulag and the men who ran it in “Oblivion”; the messy and unexamined collapse of the Soviet Union in “The Year of the Comet”; and the tragic fates of Germans in Russia and the U.S.S.R. in “The Goose Fritz.” In “Untraceable,” he looks to the more recent past to write what he calls “a contemporary Faust, but in a world where science does not have the goal of creating good but creating monsters. It’s a book about the dark romance, the long relationship between the state and scientists and their unnatural union.”

The “unnatural union” of collaboration with the regime is a subject that is virtually taboo in Russia. “Any conversation that leads directly to the idea responsibility gets blurred,” Lebedev said. “We can talk about the victims of Soviet regime, but we somehow separate that from the crimes and criminals… We have an idea, a very weak idea, of what exactly was done to the victims, but we never talk about who did it.”

In the novel, the main characters do not set themselves free from their pasts. But one man does, a priest, “a real person from the [East German] Stasi archives,” Lebedev said. “With him, I tried to show that when the whole world is against you, you can stand up to it. You probably can’t be a hero… but through him we see that you can always act differently. Always. The door is always there.”

Antonina W. Bouis, who translated three earlier novels by Lebedev, told The Moscow Times that he is “really the only Russian writer who writes about Russia today and deals with the moral issues. That used to be the writer’s obligation in the golden age of Russian literature—Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Turgenev all sought to shine a light on the society and lead their readers toward a higher good. That doesn’t happen much in today’s literature.”

The pleasure of translating him also lies in Lebedev’s rich language and imagery. “I love living in his brain and spinning out the words into English. Translating Lebedev is a challenge and a pleasure; in his novels, almost every paragraph is a prose poem. ‘Untraceable’ is more plot-driven than ‘Oblivion,’ ‘The Year of the Comet,’ and ‘The Goose Fritz,’ but just as beautifully written, just as philosophical, and just as timely.”

“Untracebale,” like a train, slowly rolls through the past, picking up speed toward the denouement, as the two assassins – whom Lebedev calls the novel’s “Rozencrantz and Guildenstern” – seem thwarted by fate but doggedly pursue their mission. Until the very last pages it is not clear if the lead agent, Shershnev — whose name echoes the wasp in the assassination that began the story — will succeed.

“I am not sure that even the best literature can change the world… but it’s important that it’s out there,” Lebedev said. “You write for the long term. I don’t know if this is a major book – only time will tell – and even major works don’t explode instantly like a grenade. But something changes when a book enters the world.”

A chemist by education, Kalitin knew a lot about the human body, but only from a narrow and specific point of view: how to kill the body. He had a fairly good idea of modern methods of treating cancer, some of which were distantly related to his research; after all, on some level he had studied the directed destruction of specific cells.

But he remained ignorant in medicine. His academic, theoretical thoughts about death and his routine closeness to it in the laboratory gave Kalitin the perverted arrogance of a technocrat who believes that destruction and creation, killing and healing were equally possible; anything that could be broken could be fixed—thing, body, spirit—it was the job of other specialists who would be at hand when needed: repairmen, doctors, psychologists.

He who developed substances from which there was no salvation, who knew the effect of their virulent molecules, still believed childishly that salvation was always possible in the case of an ordinary illness, it was just a question of timely intervention, a question of means, effort, and price; Kalitin was prepared to pay the highest price.

He could afford a good hospital. Good doctors. But that was not enough for firm hope. It would be stupid to expect help. They let him know that more than once. The invitation to consult the investigative group was a farewell gesture, a perfunctory administrative kindness. They knew or guessed that most likely he would be gone in a year. National frugality: squeeze the last of the toothpaste from the tube. He had to work off the hospital bills, balance the debit-credit, for his insurance would not cover everything. And then there was the funeral.

They didn’t tell him over the phone which crime the group was investigating. Secrecy. Not over the phone. What do they know about secrecy? In his ancient past, an armed messenger would come to Kalitin with a sealed envelope in a sealed pouch. Secrecy. . . As if he couldn’t guess since it was all over the news- papers. Anaphylactic shock or its simulation. It was probably a substance of natural origins. Not his lab, not his work. In a restaurant, at close distance. Before witnesses. Risky. He didn’t die right away, he held on, whispered. Distance? Dose? Method? Weather? Specific information on the organism? Food? Incidentally, it wasn’t clear whether he had time to eat or not, what he had eaten didn’t interest the press at all, and there wasn’t a word about alcohol, the stupid fools. Interesting, interesting … He had to read about it some more.

In the first few years after his defection, Kalitin had not read any newspapers. The news did not interest him. The laboratory, his baby, was back there in his homeland that betrayed him. Research was frozen and the staff given unpaid vacation.

He had hoped that they would believe him here and give him resources and colleagues. He would restore his arsenal and continue his interrupted research. Special services, Kalitin told himself, were the same everywhere. Certainly former enemies from the other side of the Iron Curtain, who had to collect information on his laboratory grain by grain and who had seen his creations at work—they would understand what goods he was bringing: excellent, with prospects, invaluable.

Interrogations, checks. His fate was decided slowly, with difficulty, but he waited and hoped. They scraped him clean, got everything out of him—except for Neophyte, his last secret; a substance that was not yet fully documented. Kalitin also did not tell them about what they called testing on dummies in his laboratory.

In the end, they gave him the chance to stay. They hid him from the bloodhounds. But they gave him an insignificant, albeit very well-paid, job as an outside consultant in investigations dealing with chemical weapons.

It was like rubbing his nose in it: you made the mess, you clean it up.

Kalitin tried hinting again that he could resume his work.

They promised to try him in that case.

It was only then that he realized they were handling him carefully, like a chemically dangerous substance, like a contaminated site. They put him in isolation so that no one could find and use him. In the end, it was much cheaper to pay him a salary and keep him under control than to fight the monsters he could create all over the world.

So he had received the desired recognition from his former enemies: they knew his value and that was why they put him under lock and key. They seemed to understand—and there had been psychologists among the interviewers—that he had been capable of making a break only once in his life, and he used it up, would never try again.

He relaxed and accepted the painful and impossible.

In 1991 he had just a few months left to complete the synthesis and prepare his best creation for testing. The most stable, the most untraceable substance. Neophyte. To create not an experimental version but a balanced composition ready for production.

For many years that ideal eluded him. But Kalitin overcame all obstacles, solved scientific puzzles, obtained increased financing. He felt that the birth of the desired higher substance could no longer be stopped, that it was as inevitable as sunrise.

Of course, the administrative organism was already sick, falling apart as if the country had been poisoned. Delays in equipment. Delays in salaries. The uncertainty of the bosses. The unnoticeable van disguised as a bread truck stopped coming with its delivery of dummies from the prison. He needed another three, two, even just one.

Kalitin had nothing of his own. They delivered everything to him, extracting it from the bowels of the earth, gathering it at factories, if necessary buying it for hard currency abroad; if they couldn’t buy it, they stole it, copied it, or manufactured a single device at an experimental factory at unbelievable cost.

Suddenly this horn of plenty that covered every possible register and classification from bolts and wires to rare isotopes stopped working. Dried up.

Worst of all, Kalitin no longer felt the directing and demanding will of the state in the people who had always been his trusted connections.

Even when the Party had declared perestroika and glasnost, they had laughed and assured him that the changes would not affect their industry. Now the bosses vacillated and started conversations on conversion and disarmament, unheard of in the past.

Kalitin remembered the day they told him the work would stop temporarily: allegedly they had to resolve issues of the laboratory’s administrative subordination.

For the first time in his life, he felt that there existed something higher than him, higher than the laws of chemistry and physics, which he learned to understand and use. Kalitin knew how to overcome everything: rivals’ scientific intrigues, arguments between industrial and military bosses, the mysteries of matter; he had an inner power that broke through all human obstacles. And then the Soviet Union collapsed, an unknown force brought down the previously immutable building of the state, and the production version of

Neophyte died under its rubble.

He had never seriously thought about God and had worked fearlessly in his laboratory set up in the defiled chambers of a former monastery; on that one day Kalitin felt what he imagined was God for believers. The dark, impervious strength of matter that resists scientific understanding. That is afraid of titans like Kalitin who had begun a new era in science by learning to look deeper than other scientists into the essence of things—thanks to the merger of the technical capabilities of mass industry and the unlimited power of the planned state economy, which could concentrate previously unheard of resources on the achievement of a scientific goal and give the select scientists not only the means but also the direct, grievous power to achieve it.

Kalitin was experiencing the dull bewilderment of total collapse. He could not take revenge on the destructive power or overcome it. But he so wanted to take revenge on its accomplices, those brainless fools, the cautious bosses, the craven generals with big shoulder boards who could manage nothing more than a cartoon coup attempt, their knees shaking! Or the blind people who wanted something called a free life, stupid people who abandoned their sensible places and labors!

When Kalitin fled soon after, he took this hidden thirst for revenge as his guide. But as years passed it became clear that he had made a shortsighted mistake.

He had rushed.

When the former enemies rejected his knowledge and services, Kalitin could only dream of the restoration of the USSR. There was no life for him outside the laboratory, and a laboratory was possible, he thought, only inside the Soviet Union. He desired that resurrection with a passion greater than that of the million hard-core Communists who rallied in 1993, when the crowd, drunk on the red of hundreds of flags, crushed a police man to death. He prayed—with the ungainly, doomed prayers of an atheist—to his Neophyte, the unborn divinity of secret weapons, calling on its help if it ever wanted to appear in the world in all its power.

Excerpted from “Untraceable” by Sergei Lebedev, translated by Antonina W. Bouis and published by New Vessel Press. Copyright © 2019 Sergei Lebedev. Translation Copyright © 2021 Antonina W. Bouis. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For more information about Sergei Lebedev and his books, see the publisher’s site here.