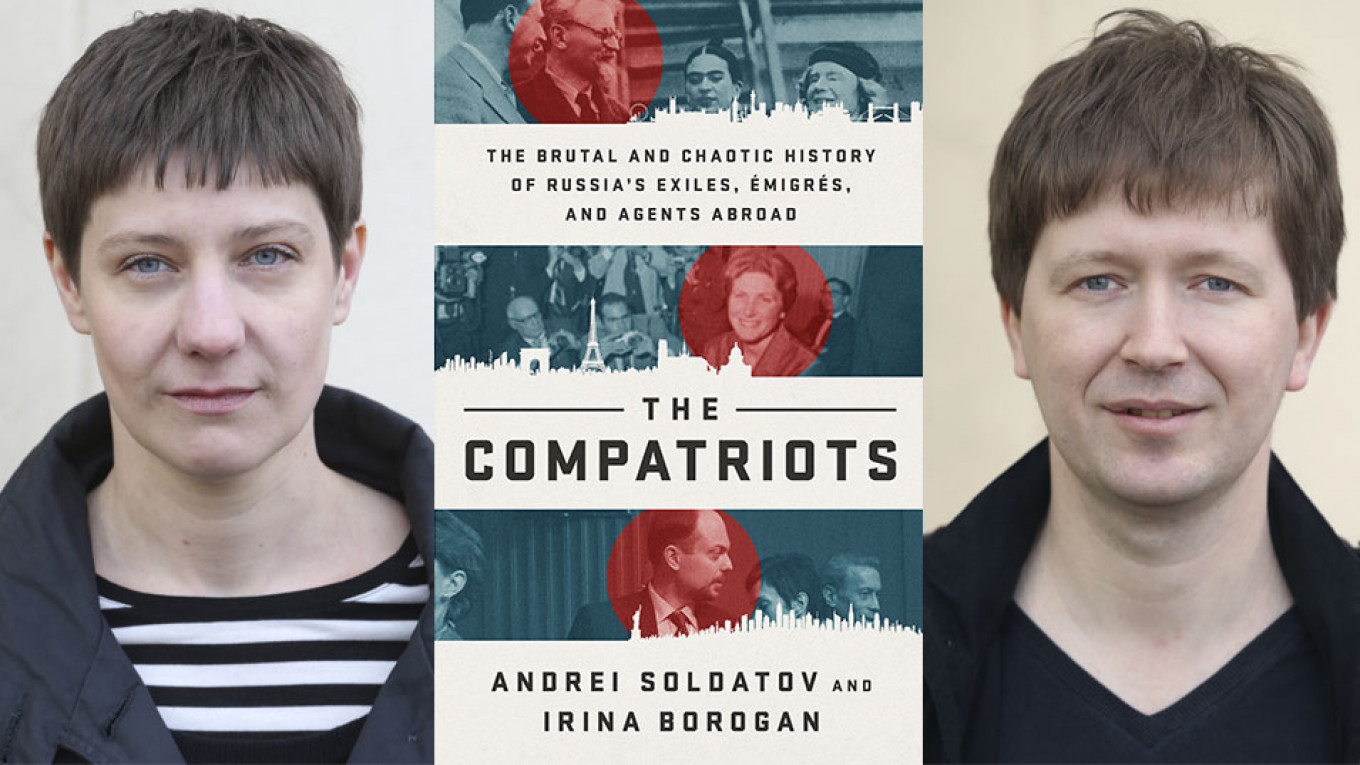

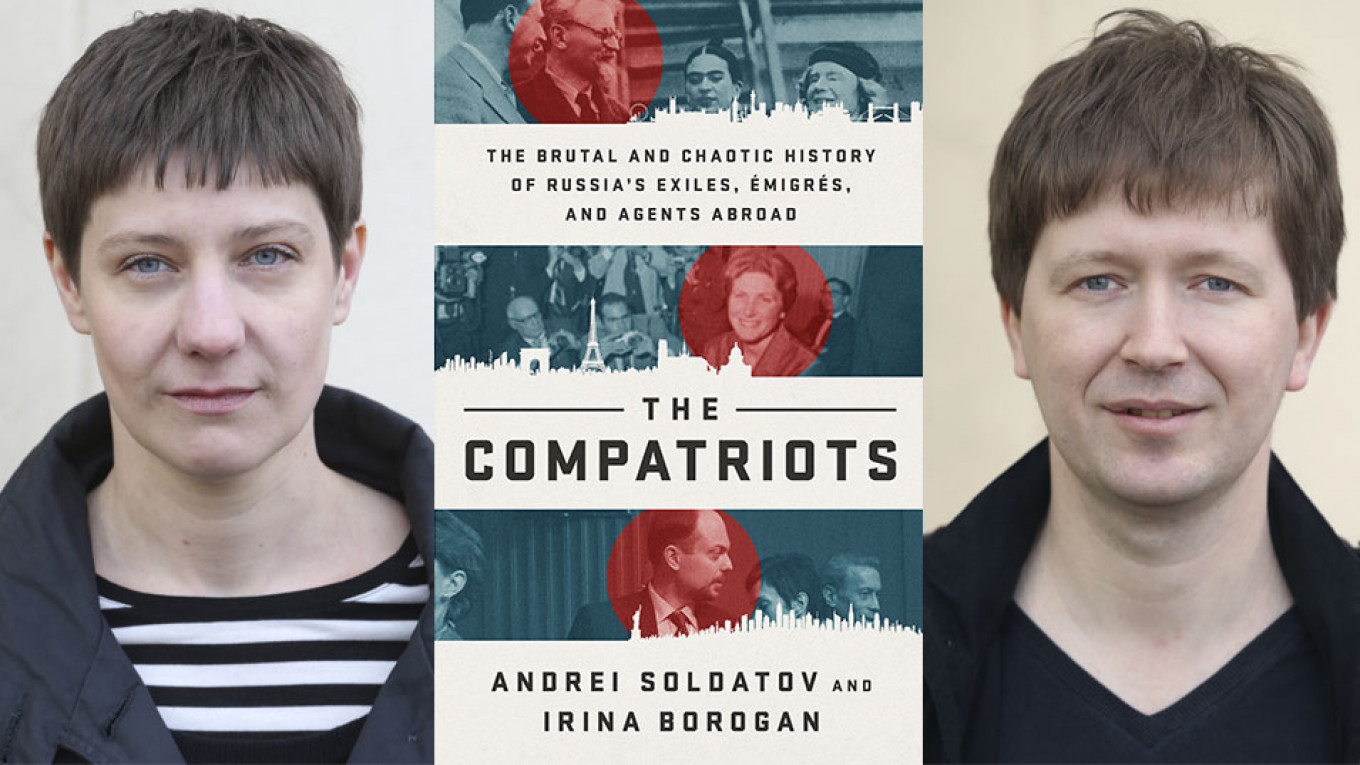

Investigative journalists Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan began to concentrate on the Russian security services with the site Agentura.ru in 2000. Their latest book, published in October, is “The Compatriots: The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia’s Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad,” which follows four other volumes.

“The Compatriots” looks at the work of the Russian security services abroad from the 1917 Revolution until today. We caught up with author Andrei Soldatov to ask him about the book and some of the bigger issues that he and Bogoran raised in it. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why was it important to begin this story with events of 100 years ago?

We’ve been writing about the security services for almost 20 years, and when you write about something for such a long time, you begin to have your own ideas. Before we started research for “The Compatriots,” we thought the foreign intelligence agencies had been reformed and were completely different from the KGB. But when we began our research, we were astonished to discover that they had inherited a great deal from the foreign intelligence services in much that they do today – methods of work against political exiles, how they perceive their role. And it turned out that the foreign intelligence is exactly like the KGB… When we understood that, we realized that we needed trace things back to the origins: how it all started, why it started this way, why they use the same techniques today — telling the story through human stories, in fact, through family stories.

Where did the myth of the reformed foreign intelligence services come from?

The foreign intelligence services realized even before the Soviet Union collapsed that no one would help them — not Gorbachev or even the KGB leaders on Lubyanka. They needed to save themselves. In 1990 they made the crucial decision to have the disinformation unit save the SVR [Foreign Intelligence Service] from reforms and dissolution. They came up with the idea of presenting the SVR as intellectuals, much more liberal than the KGB, people who knew something about the West and had never taken part in any persecution of dissidents. It’s completely untrue — it has nothing to do with reality. But the image has stuck.

Poisons have been used from the start. Why?

It’s psychology… Poisoning is about torture from the inside. It takes a long time. It’s not a click or one minute, it’s about days and days and sometimes weeks. People physically change. You don’t recognize the person you used to know. It has a big psychological impact on everyone around you. Almost everyone we spoke with for the book – political emigres, oligarchs in exile, even priests — all raised the issue of the Skripal case and poisoning. It had an effect. It’s very frightening.

Why was the West so bad at stopping them?

First of all, in the U.S. you were busy with other problems like the mob. And then it was hard to understand if it was espionage or not. You can’t accuse all the members of the American Communist Party of being Soviet spies, because they weren’t. They gathered intelligence for the Soviet Union, but they never knew it. That was the beauty of the system and why it was so effective. It’s very difficult to understand if someone is a traitor or a guy inspired by an idea.

You wrote that Russian intelligence was a “self-reproducing circuit.” How does it work?

The big mistake we journalists made back in the late 1990s and 2000s was thinking that the oligarchs were smarter and much more resourceful than all these guys from the KGB. But they were a system. Oligarchs were smart and brilliant, but they lacked a system. They fought each other, they had different backgrounds, they were too individualistic. These guys weren’t. In Russia, you need to be recommended by someone in the FSB, usually a family member. You go to the FSB academy right after grade school. You spend many years together and then it’s your family background. It makes you very separate from the rest of the population.

So will this gone on forever?

It’s true that the government is obsessed with political exiles and emigration, and the intelligence services are using the same methods. But we live in a completely different reality. The borders are still open, and we have internet. It’s harder to control everyone.

People leave the country, but they don’t shut the door, they can come back — if not physically then through internet. We are not living in a universe where Russia is behind closed doors. That makes me more optimistic.

***

From “The Compatriots: The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia’s Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad”

Chapter 4: “The Horse”

Well into the late 1930s, Soviet intelligence kept hunting down Stalin’s archenemy Trotsky. Trotsky’s archive was stolen in Paris; his son mysteriously died after what seemed like a rather simple surgery; his closest associate was kidnapped, and his body was later found in the Seine. Moving from Turkey in 1933, first to France, then to Norway in 1936, Trotsky left Europe for Mexico. When he did so, the city of New York suddenly became important for Lubyanka. After all, New York was an important center for Trotskyites’ activities, and geographically it was closer to Latin America than other émigré centers. After giving the topic careful consideration, Soviet spymasters came to the conclusion that local activists could provide a point of access to Trotsky himself.

At a prewar co-op building in Greenwich Village, just two blocks south of Union Square, there was unusual, even feverish, activity: gloomy men from Moscow who called themselves Richard or Michael came and went frequently from the ninth floor. The ninth floor was home to the offices of Earl Browder, head of the Communist Party in the United States. What most New Yorkers didn’t know was that the US Communist Party owned the entire building. And right now, the US Communist Party was in a state of mobilization.

The American names of the visitors with strong Russian accents didn’t suit them very well. Everyone understood these gloomy men were coming straight from the Soviet secret police. And the Richards and Michaels brought urgent orders: US Communists were to gather information on Trotskyites.

Browder’s deputy, Jacob Golos, was happy to help. Golos was a legend in the Comintern and Soviet intelligence. A Russian Jew who belonged to the first generation of Bolsheviks, Golos had been banished by the tsar to Siberia for organizing an underground printing house but had escaped his Siberian exile and fled first to China and then to Japan before finally making it to the United States. In I9I5, he became a naturalized US citizen. With a prominent nose and curly hair, the energetic Golos — who never lost his heavy Russian accent — was a founding father of the Communist Party of the United States.

Golos had a God-given talent for recruitment. Few could compete with him. In New York, he ran several networks, each with dozens of agents. As an ardent Stalinist, infiltrating local Trotskyite organizations was at the top of his priority list. When the Moscow men asked for contacts, Golos knew just who they needed.

One meeting that would prove crucial was arranged between a gloomy Russian and Ruby Weil, a young American woman from Indiana. Then in her early thirties, Ruby was a secret Communist, trained in infiltration techniques. Her job was to penetrate international Trotskyite organizations, and she was good at it.

The Russian knew that Ruby was on very friendly terms with Hilda Ageloff. Hilda was one of three young, sociable sisters who knew Trotsky personally. Indeed, two of the Ageloff sisters had done secretarial work for him. At their meeting in New York, the Russian introduced himself to Ruby as John Rich. He told Ruby he had plans for her: she was going to do an important job for her Soviet comrades. Ruby was handed a stack of cash. At first, Ruby was reluctant to take the money. She was a Communist out of conviction, not for material gain. But she was told it was important for her to be better dressed. She would also need the money to pay her phone bills. There was a plot against Stalin’s life, she was told, and her help was needed. So she agreed.

Her task, as outlined by the Russian, was not difficult: Ruby was to accompany one of the three Ageloff sisters—Sylvia, a twenty- eight-year-old Brooklyn social worker and occasional secretary to Trotsky—when Sylvia traveled to Paris to participate in a Trotskyite international congress. Bespectacled, shy, and slightly awkward, Sylvia was a polyglot, fluent in Spanish, French, and Russian (the sisters’ mother was from Russia). In Paris, Ruby’s job was to introduce Sylvia to a certain man who would make himself known to Ruby when they arrived.

Ruby got started right away. She was almost immediately lucky—Sylvia was more than happy to have a traveling companion and especially one who also believed in communism.

The trip across the ocean took many days but was pleasant, and the young women arrived in Paris in June 1938. While Sylvia stayed behind at their hotel, Ruby said she needed some fresh air. Once alone, she made her way to an address she had been given by John Rich to meet a comrade named Gertrude. It was this Gertrude who introduced her to Stalin’s agent. The agent, a young and handsome man, said his name was Jacques Mornard. When Ruby saw him, she immediately grasped his role: that of a handsome lover for Sylvia.

Ruby took Jacques back to the hotel where she was staying with Sylvia and made introductions. Ruby’s new acquaintance told Sylvia he was a Belgian businessman who was enjoying himself in France. He seemed completely disinterested in politics and had a great passion for theater and music. Sylvia quickly fell for Jacques, and they spent seven wonderful months together in Paris.

What Sylvia didn’t know was that her Jacques was in fact a Spaniard named Ramon Mercader, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. For now, his job was to cultivate this new relationship and wait.

For ease of reading, footnotes have been removed from this excerpt.

Excerpted from “The Compatriots: The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia’s Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad” published by PublicAffairs, Hachette Book Group.

Copyright © 2019 by Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For more information about the authors and their books, see the publisher’s site.