Lobsters, crabs, crawfish… what could be further from Russian cuisine? Actually, that’s not right, if only because all kinds of European seafood have been part of Russian culinary tradition for more than 250 years.

In 1766 Catherine gathered together the most prominent scientists of the time and gave them a difficult task. She demanded that they search the Baltic Sea for the crab and lobster she loved so much. This was an expensive pleasure, but the state treasury was not tight with their funds, and they gave what was at the time enormous sum of money to carry out sea and land expeditions along the coast. Sadly, no lobsters were found. But the scientists did make many discoveries and even laid the groundwork for ichthyology in Russia. And all kinds of seafood found their way to the Russian table.

But, of course, lobsters hold a special place in the science, culture and city of St. Petersburg. Let’s immerse ourselves for a moment in the history of 200 years ago.

By a twist of fate, a young 22-year-old Scotsman named James Wylie found himself in Russia in 1790 where he quickly was renamed Jakob Vasilievich Villie. He joined the service as a medic in the 33rd Yeletsky Infantry Regiment, where he soon showed professionalism and ingenuity. As often happens, chance played a role in his fate. In 1799 the young physician successfully operated on the father of Count Kutaisov, a general and a very important dignitary. At the request of his new patron, Wylie was appointed the emperor Paul I’s lieutenant-surgeon.

Wylie became the palace physician of three emperors. He signed the medical report on the death of Paul I “from apoplexy” (and not from being hit with Count Nikolai Zubov’s heavy gold snuffbox). With the new Emperor Alexander I, the Scottish physician went through the Napoleonic campaign. After his defeat at Austerlitz, Wylie together with his aide-de-camp, accompanied the Tsar, who miraculously escaped captivity. When the horse emperor was riding fell, the adjutant rode away, but the faithful doctor carried the tsar off on his horse.

In 1808, barely forty years old, Wylie became the first president of the oldest higher medical school in Russia, the Petersburg Medical and Surgical Academy (now the Military Medical Academy). In honor of the 50th anniversary of his selfless service to Russia, in 1840 a commemorative gold medal was minted.

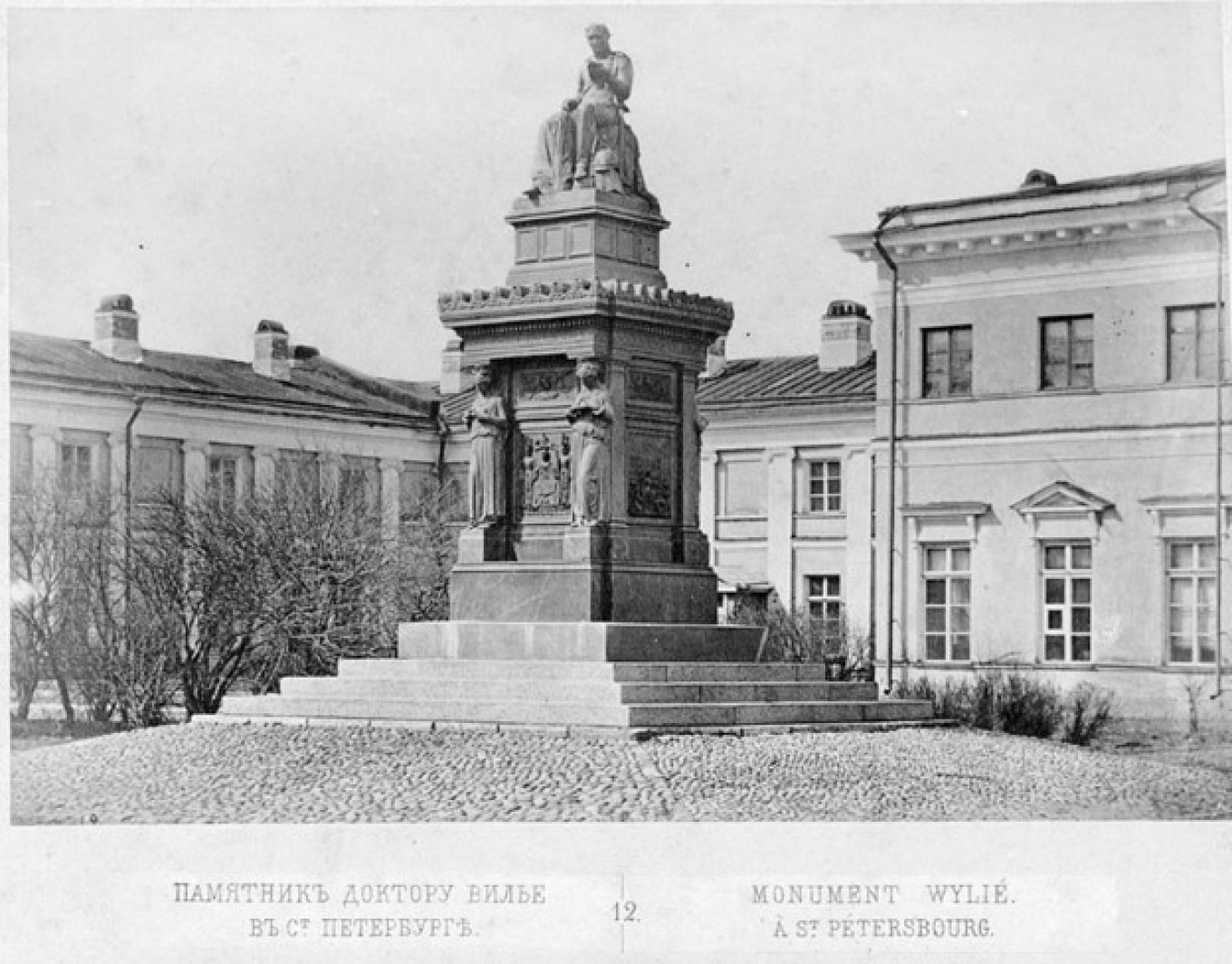

Shortly after his birthday Wylie made an unexpected gesture. He divided all of his then considerable fortune into three parts: he set aside 100,000 rubles for scholarships for exceptionally gifted university graduates and he left a small sum for a monument to himself. He also gave 1.2 million rubles to build a public hospital. After his death in 1854, the Medical Surgical Academy built a clinic. And today this building stands at the corner of Botkin Street and Bolshoi Sampsonievsky Prospekt. And in front is a monument to this outstanding Scotsman who served Russia and the Russian imperial families.

So what does this have to do with lobsters, you might ask. It’s simple. Wylie originally wanted to bequeath 80% of his fortune to his brother. But according to a family legend, one day at dinner the brothers got into a fight: Wylie’s brother wouldn’t share his lobster. The fight was so bad that Jacob disinherited his brother. “And because of those lobsters, an enormous clinic was built in St. Petersburg for the benefit of all mankind,” the Physician’s Gazette later wrote.

That said, lobsters and other crustaceans weren’t a rarity in Russia at the time. They were imported from abroad and widely available in “good stores.” A recipe for cooking lobster was included in the “Cook’s Dictionary” written by Vasily Levshin and published in St. Petersburg in 1795. A recipe for lobster mayonnaise can be found in the “Almanac of Gastronomists” (1855), a book by the famous Russian chef Ignaty Radetsky. In those years, mayonnaise was not just the sauce, but dishes made with it. For example, a dish might be called “mayonnaise of game and sturgeon.”

But lobster, state service and public health aren’t all that Wylie was famous for. There is another curious aspect to his life story.

James Wylie was a close friend and comrade-in-arms (in the French campaign) of Count Alexander Apraksin. He, in turn, was the godfather of Alexander Blank (1799-1870). The Count was very involved in the life of his godson, but it was Wylie who helped him get into the Medical Surgical Academy. Wylie took an interest in the young man and encouraged the talented cadet in his studies. Later (1832) during his residency, the obstetrician Alexander Blank lived with his wife and children in the Wylie’s house on the English quay. Here in this house Masha Blank was born in 1835.

In Russia she is better known as Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanov, the mother of Vladimir Lenin.

Even the monument to Wylie had a twist in its fate. For almost a century it stood in front of the main building of the Military Medical Academy. But in 1948 during the campaign against cosmopolitanism, the long-deceased physician was, it suddenly turned out, an English spy. The monument was dismantled, and from 1949 to 1964 it was not accessible to the general public.

It was put up again not in front of the Military Medical Academy, but in a small park near the Mikhailovsky Hospital — the hospital built on “lobster money.”

But Russia’s epic love affair with seafood did not end here. In the 1930s and 50s crabs appeared on Soviet store shelves and were even exported under the brand name CHATKA. They were good in both simple salads and in intricate banquet dishes.

The building of communism, announced by Nikita Khrushchev in the early ’60s, caused quite a stir in society by 1980. In fact, by that time, the lack of basic foodstuffs was becoming more and more apparent. No one could find crab and lobster on store shelves. Ordinary cans of squid were becoming a holiday meal.

And then the Soviet authorities decided on an experiment: crab sticks. Invented in Japan, by 1984 they were being produced at a Murmansk factory called Protein. At the time Soviet people thought this was a delicacy. Its taste was different from today’s versions. The technical specifications of 1985 stated that this imitation crab meat was to be made with minced shrimp or cod fish with flavorings and crab meat essence. Modern production and advances in the chemical industry have changed the ingredients somewhat, but the principle remains the same — the more expensive it is, the more natural it is.

Crab stick salad was a great hit of Soviet cuisine for many years, and even today it is served on holiday tables. Let’s not forget this simple and inexpensive dish.

Crab Stick and Red Caviar Salad

Ingredients

- 150g (about 5 ½ oz) crab sticks

- 3 eggs

- 1 orange

- 100 g (3.5 oz) canned corn

- 2 Tbsp red caviar

- 2 Tbsp mayonnaise

Instructions

- Boil eggs and then cool them.

- Peel orange and remove pith.

- Dice crab sticks, orange and eggs.

- Put all the ingredient in bowl, mix gently and dress with mayonnaise; add a dollop of caviar on top.

- Salt to taste (if the caviar isn’t salty enough).

Leave a Reply