A dispute once arose in a Moscow liberal drawing room in the late 1870s. Did the heir to the throne (the future Tsar Alexander III), who considered himself purely Russian, have much Russian blood in him? The dispute was resolved by turning to the famous historian Sergei Solovyov, who happened to be among the guests.

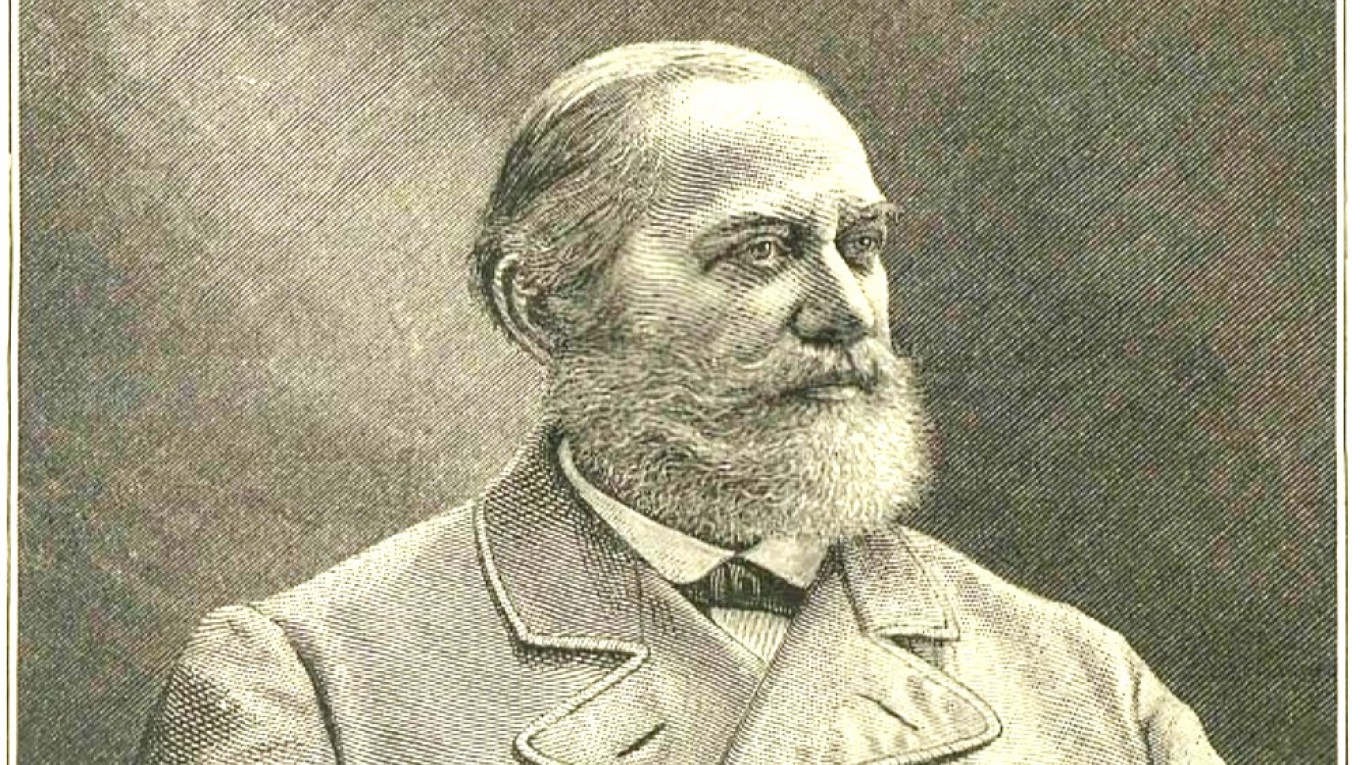

The first volume of Solovyov’s most famous work “The History of Russia from the Most Ancient Times” was published in 1851, bringing the historian Russian and European fame. In total, he wrote 29 volumes (one volume was published every year), covering the history of Russia up to the reign of Catherine II (up to 1774). The last 29th volume was published posthumously in 1879.

The scholar was considered by the royal family to be an authority on Russian history. He taught the tsareviches Nicholas and Alexander (royal heirs to the throne) and and gave lectures to Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich. So the public’s question was addressed to an undisputed specialist.

Solovyov asked for two glasses of water and some red wine be brought to him. He poured half a glass of red wine and half a glass of pure water.

“Let’s say the red wine,” he said, “is Russian blood, and the water is German blood. The Russian Peter the Great married a German woman — Catherine I….” With that, the historian poured half a glass of red wine into a glass half-filled with water.

“Their daughter Anna,” Solovyov continued, “married a German, the Duke of Holstein.”

The historian poured out half a glass of the wine mixed with water, and again added water. He repeated this process as he cited the marriage of Peter III to the German Catherine II, Paul I to the German Maria Feodorovna, Alexander II to the German Maria Alexandrovna… In the end, he held a glass with almost pure water.

“Here,” said the historian, raising the glass, “is how much Russian blood the heir to the Russian throne has!”

To be exact, Alexander III had 1/64 Russian blood to 63/64 of German blood. The last Emperor Nicholas II had 1/128 Russian blood.

The same amusing mix in the two cousins is not only a characteristic of the royal dynasty, but for all Russian culture — including the kitchen, which is such an important part of culture. The eternal battles between “Westerners” and “Slavophiles” are not just a reflection of the political currents of the late 19th century. They are really about the whole of Russian history, where the (unsuccessful) struggle with Western values and culture is a permanent part of everyday life.

The approaching holiday of Halloween is this month’s irritant for Russian pseudo-patriots. For a while now costumes and pumpkin jack-o-lanterns have become the enemy of Putin’s spirituality. It always makes us laugh that the pumpkin bothers them so much. Are Russian values really so weak that they can be defeated by a pumpkin?

Nevertheless, some Russian schools this year will celebrate the hastily invented “Pumpkin Feast of the Savior” on October 30 instead of the God-awful Western pumpkin party. Invitations make it very clear that children are expressly forbidden from dressing in costumes of “unclean spirits.”

But the truth of the matter is that the pumpkin is part of Russian culture!

Most people think that the victorious spread of the pumpkin around the world began in Central and South America. But actually in 1926 a wild variety of small pumpkin was discovered in North Africa by an expedition led by Academician Nikolai Vavilov. It grew in the same places as wild watermelons. So there is no definitive answer to the question of where and how the pumpkin came to Europe.

In Russia, pumpkins appeared in the 16th century. They either came from the East, brought by Persian merchants who came to Derbent, Astrakhan and other cities with goods, or from the West by Moscow merchants, who by that time had already established close trade relations with the countries of Western Europe. In the 16th century the pumpkin was very popular in Europe. The Russian climate was good for cultivating pumpkin almost everywhere, but it became widespread only beginning in the 18th century.

Undemanding, yielding large crops and easy to store, the pumpkin quickly became widespread in many southern regions of Russia, so much so that the inhabitants of those regions consider pumpkin to be a native Russian crop.

Pumpkins appear in the very first cookbooks in the late 18th century. For example, “Russian Cookery” written in 1795 by the famous culinary specialist Vasily Lyovshin, has recipes for fried pumpkin, pumpkin stuffed with meat, milk porridge with pureed pumpkin, and pureed pumpkin soup. The soup is something of an imitation of Western traditions, but also a fine example of the ability of Russian cuisine to assimilate foreign culinary ideas. By the 18th century, pumpkin had become quite a Russian vegetable.

In the fall, we often cook pumpkin. Here’s a dish that combines traditional Russian and foreign ingredients and cooking methods. The combination of the sweet pumpkin and tart cheese is a delicious blend of east and west.

Baked Pumpkin with Gorgonzola

Ingredients

- 600g (1.3 lb) pumpkin

- 200g (7 oz) white bread — preferably wheat-rye (not pure rye) or light brown bread

- 200ml (1 c less 2.5 Tbsp) cream with 20% fat content

- 2 eggs

- 2 yolks

- 1 tsp sugar

- 180g (generous 6 oz) gorgonzola (or other blue mold cheese)

- olive oil

- salt, freshly ground black pepper

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 190°C/ 375°F.

- Cut the pumpkin into small pieces, drizzle with oil, sprinkle with salt, pepper and sugar. Bake in the oven until cooked through and then cool.

- Cut the bread into small cubes and lightly dry in the oven.

- Peel the pumpkin and mash it lightly with a fork.

- Beat the eggs lightly with a fork; mix in cream and pumpkin. Add the bread, stir and add pieces of gorgonzola. Season to taste with salt, pepper, a pinch of sugar. Pat the mixture into a greased baking pan and place it in oven. Turn the temperature down to 180°C/355°F and bake for 40 minutes.

- Serve hot or slightly cooled.