If you ask anyone to describe Russian cuisine, one of the first dishes that will come to mind will certainly be blinis. They are a truly iconic dish that is now an integral part of folk life and tradition. The only problem is that there as many myths and fabrications about them as there are about the rest of Russian history.

The entire next week starting Feb. 20 is Maslenitsa or “Cheese Week” in Russia, the week before Lent begins. This means caviar, sour cream and blinis with a glass of vodka.

And in honor of Maslenitsa, here is everything you wanted to know about Russian blinis but were afraid to ask.

“Blinis are baked, not fried.” This is truly the essence of blinis. Blinis really are baked. And without a lid! This is simply a feature of the Russian stove, where the heat comes from all sides. You can make them in a skillet, too, but then you need to flip them.

Blinis are certainly not a Russian invention. They were made in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. The idea of pouring liquid batter on a heated stone and baking it has been around for several thousand years. The only difference is that these delecacies became widespread and popular in Russia.

One of the oldest types of Russian blinis are kotloma. The name probably came from the Turkic languages. “Catalog of the Tsar’s Meals” (1610-13) notes: “For a dish of kotloma, mix spadefuls of gritty flour, liquid honey, 25 eggs, 10 grivnenkas (2 kg) of butter made from cow milk.”

Blinis were not historically part of Shrovetide festivities. There are no written records about them until the 16th century. The reason they became part of the pre-Lenten holidays was simple: Under Ivan III the New Year was moved to Sept. 1. That made it possible to weave the old pagan spring festival, where the round, sun-like blinis were served, into the structure of the Orthodox Christian calendar. The pre-Christian holiday was tied to “Cheese Week” (Maslenitsa), the last week before Great Lent.

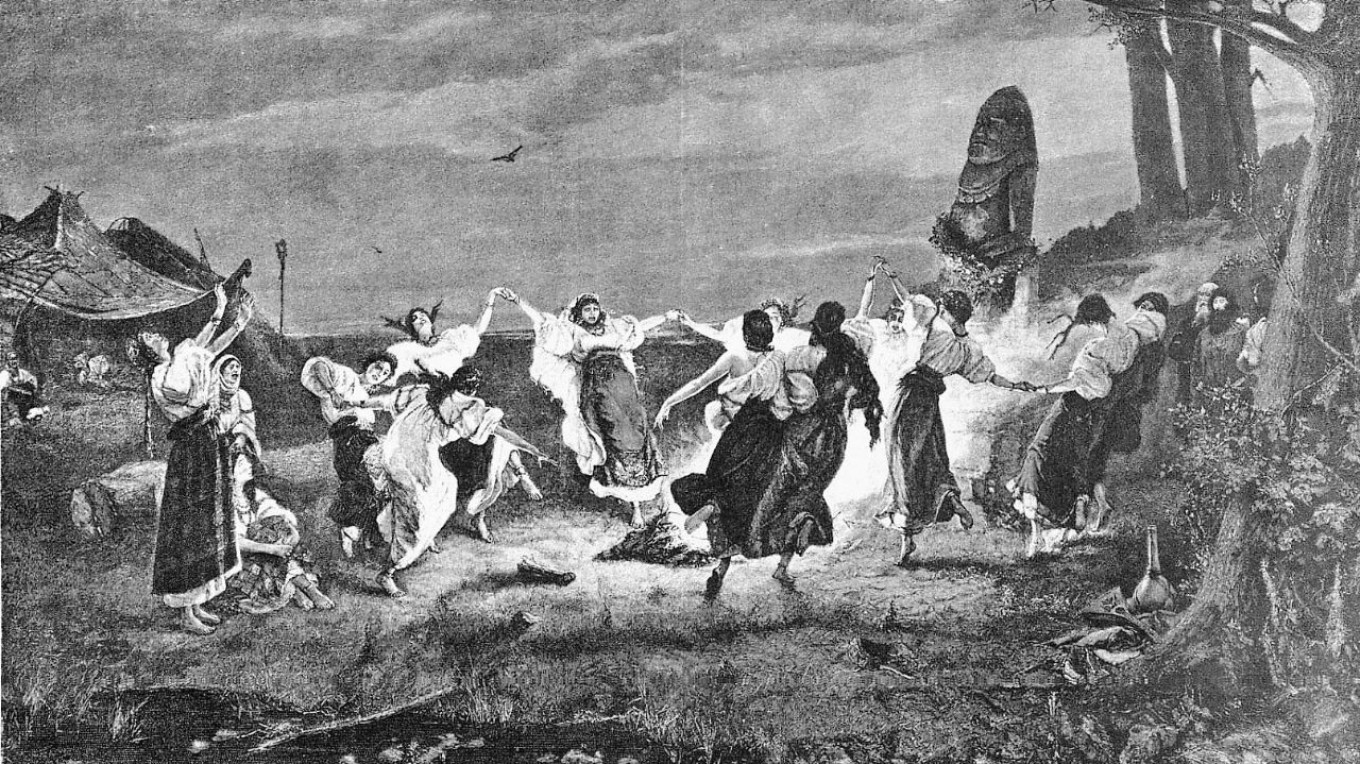

The story of Maslenitsa is a vivid example of how the church appropriated many pagan festivals and customs. For centuries there had been a pagan celebration to meet spring in Russia, when people jumped over bonfires, burned an effigy, ate blinis, pies, and the like. There is no evidence that the pagan holiday was tied to a specific date. It was celebrated at the turn from winter to spring. The church, on the other hand, tied it to the celebration of Easter.

In this way the church “conquered pagan superstitions” on the one hand, and on the other, it preserved the folk tradition of a holiday with a lot of food. A great variety of dairy foods were consumed: sour cream, cream, cottage cheese, butter, milk, as well as eggs, fish, various grains, pies, and blinis.

A popular type of Russian pancakes were alady. Russian historian Nikolai Kostomarov (1817-1885) writes: “Big alady were called “ordered alady” because they were served to clerks” — that is, employees of state administrations. So blinis were once a way of expressing gratitude or offering a bribe.

Blinis were not part of Shrovtide celebrations everywhere in Russia. Here is how a contemporary describes the holiday meals of the peasants of Yaroslavl province in 1849: “In Cheese Week in the morning all the housewives in all the houses heat their stoves and start cooking: they stew and fry fish in pots and pans, make pies, prepare batter for pryazhents (pies fried in oil). When the time comes they cook them in oil either alone or filled with eggs, or with berries and fish.” And the famous Russian cook of the 19th century Yekaterina Avdeyeva also speaks more about pryazhents and kvorost (thin pieces of dough that are deep fried) served during Shrovetide in Siberia.

Old-fashioned blintsy are also part of our blini tradition. What are they? They are thin pancakes with various fillings that were rolled up and then baked again in pots or pans. Vasily Lyovshin, in his 1795 “Russian Cookery” writes that they could be served with korinka (raisins) and millet porridge.

Blini with “korinka”:

Boil some millet and let it sour. Then mix in korinka and a little sugar. Fill some the blintsy with some of this filling, then place them in a skillet and fry them in butter like pot cheese cakes.”

Blinis in Russia are regional. That is, each historical region has its own blini tradition. Buckwheat blinis in Central Russia; wheat blinis with smelts in St. Petersburg and Veliky Novgorod, and thin “transparent” blinis in Siberia.

There are also stuffed blinis. In the middle of the 19th century Yekaterina Avdeyeva wrote about them this way:

“Let me say a few words about the favorite old dishes that are still made to this day. Buckwheat blinis are one of the oldest. They are best prepared in Kursk, where they are eaten with butter, sour cream, caviar and black olives. The stuffed blinis are sprinkled with chopped eggs or fresh cottage cheese, and during Lent they sprinkle them with fried onions or smelts.”

Avdeyeva’s recipe for filled blinis is simple:

“Take pot cheese out from under a weight, grate it on a sieve, thin out with raw eggs. Spread baked blinis with pot cheese, first turn back four sides, then fold in half. Before the meal fry them in butter in a skillet. When one side is nicely browned, turn it over and then serve hot.”

Blinis changed as the cuisine changed, over time becoming more appropriate to the fine cuisine of the 19th century.

Ivan Navrotsky in his “New Complete Cookbook” (1808) supplements an old recipe with rum: “One may dilute the batter for olady, when very thick, with a little sweet rum; and if it is oily, add grated white bread, and then fill the whole skillet with the batter and fry them one after another.”

Ignatius Radetsky, who published the famous book “St. Petersburg Cuisine” in 1862, gives the recipe for rice blinis with Parmesan. The batter for thin rice blinis was poured into a pan and immediately sprinkled with grated Parmesan. All this was done in several pans at the same time. Once the first blinis were ready, one was flipped onto another so that the cheese filling was inside. And the whole thing was baked again. The finished blinis were stacked. The result was a kind of cheese and blini cake, whichwas served with sour cream.

In times of crises, blinis could be quite humble. Published in 1927, Katerina Dedrina’s book “Cooking on Stove and Primus” was an example of the new Soviet cuisine. This cuisine replaced the pre-revolutionary cuisine that had been “torn to pieces.” In this situation, blinis were almost primitive:

“Dilute about 30 grams of yeast in ½ bottle of lukewarm milk, stir in some flour and 3 eggs, as well as salt and 200 g of butter (or 100 g of palm oil). Put into hot milk and boil it under a tight lid.”

As you see, palm oil didn’t just appear in Russia as a cheap alternative to butter in recent years.

Kefir blinis have been made in Russia since about the beginning of the 20th century (this beverage came to Central Russia from the Caucasus relatively late). These blinis are one of our family favorites: thick, fluffy, and buttery. We will cook them for our guests at Shrovetide.

Kefir Blinis

Ingredients

- 1 liter (1 generous quart) kefir*

- 450-500 gr (3.2 to 4 c ) flour

- 3 eggs

- 3 Tbsp sugar

- 1/2 Tbsp salt

- 1/3 tsp citric acid

- 1 tsp baking soda

- Butter for the blinis

* Kefir is found in some supermarkets and most health food stores. If you can’t find it, buttermilk or plain yogurt watered to a thin consistency are good substitutes.

Instructions

- In a saucepan, heat kefir with sugar, salt and citric acid until the temperature is about 40˚C (104˚F).

- Lightly beat the eggs.

- Pour all the flour into a large bowl. Pour in half of the kefir and mix it well. Add the eggs.

- Add the rest of the kefir. The batter should be like a liquid sour cream.

- Thoroughly mix and add baking soda.

- Gentlhy stir the batter. Carefully dip a ladle into the mixture. Do not submerge it or hang the ladle on the side of the bowl.

- Grease a blini or frying pan with a piece of lard and heat. Pour in the batter, swirl it around, when browned on one side, flip to the other.

- When ready, flip onto a plate and butter generously on both sides.