Anyone who spent time in the Soviet Union remembers the cigarettes — their ubiquity, first of all, and that particular scent wafting out of windows, filling stair landings, and permeating clothing down to underwear and socks. Cigarettes were essential for making friends and getting through the workday, guaranteeing the sanctity of smoking breaks in the stairwell. And a pack of Marlboros was currency, good for catching a taxi on New Year’s morning and arranging a doctor’s appointment.

In “Cigarettes and Soviets: Smoking in the U.S.S.R.” author Tricia Starks tells the story of tobacco and smoking during the Soviet period. But perhaps it is more accurate to say that she tells part of the history of the Soviet Union through the prism of smoking.

It’s the story of politics and personalities — a smoking leader guaranteed support for the tobacco industry, a non-smoker did not — as well as the complexities of political favorites and enemies: early studies on smoking cessation had to tread carefully around ideas by Sigmund Freud and Ivan Pavlov, out of favor with Soviet authorities. It is about economics and integration into the world economy; industrial and agricultural development; the allocation of funds and movement of resources during the Great Patriotic War; the changing roles of men and women; colonialism and indigenous culture; the space race; innovation in psychology; and uprisings of public discontent and the Soviet leaders’ response to citizens’ needs and demands.

It’s a bumpy ride over the decades, as the government balances economic gains against public health, on the one hand debunking claims by some Soviet doctors that “smoking served as a disinfectant of the mouth, completely killing cholera, typhoid, and pneumonia,” while on the other hand developing a cigarette called Astmotal touted as “an anti-asthma” cigarette with a “pleasant scent.” At the same time, in the early years of the USSR innovative smoking cessation programs were developed that were decades ahead of work by their Western colleagues.

Towards the end of the Soviet Union, cigarettes were one of the keys to greater integration into the Western economies. The Phillip Morris company launched its “Mission to Moscow” to bring their brands — Marlboro, Kent, Camel and Salem — to the U.S.S.R. It began with the Soyuz-Apollo cigarettes in honor of the joint space program between the U.S. and U.S.S.R.

Throughout Starks pays particular attention to the connections between society and their smokes, used by advertisers and perhaps at times shaped by them. Early ads associated papirosy — the traditional filter-less cigarettes smoked in Russia — with workers and revolutionaries; during the New Economic Policy period the images changed to dapper men and elegant women smokers. During the war, the image of soldiers smoking cigarettes conveyed the ritual of solidarity.

Later, smoking was connected with the successes of the Soviet system, particularly the space program. Starks writes: “The masculine thrust of the propaganda on the space program coincided with an established association of men and smoking to emerge in venues like the popular 1963 song, ‘Fourteen Minutes to Liftoff’ that originally featured the astonishing lyric of a cosmonaut lighting up in the capsule prior to blast off…. A quick smoke before liftoff was nothing compared to the claim that the Soviets had the first man to smoke (and drink vodka) in space—Valerii Riamin.”

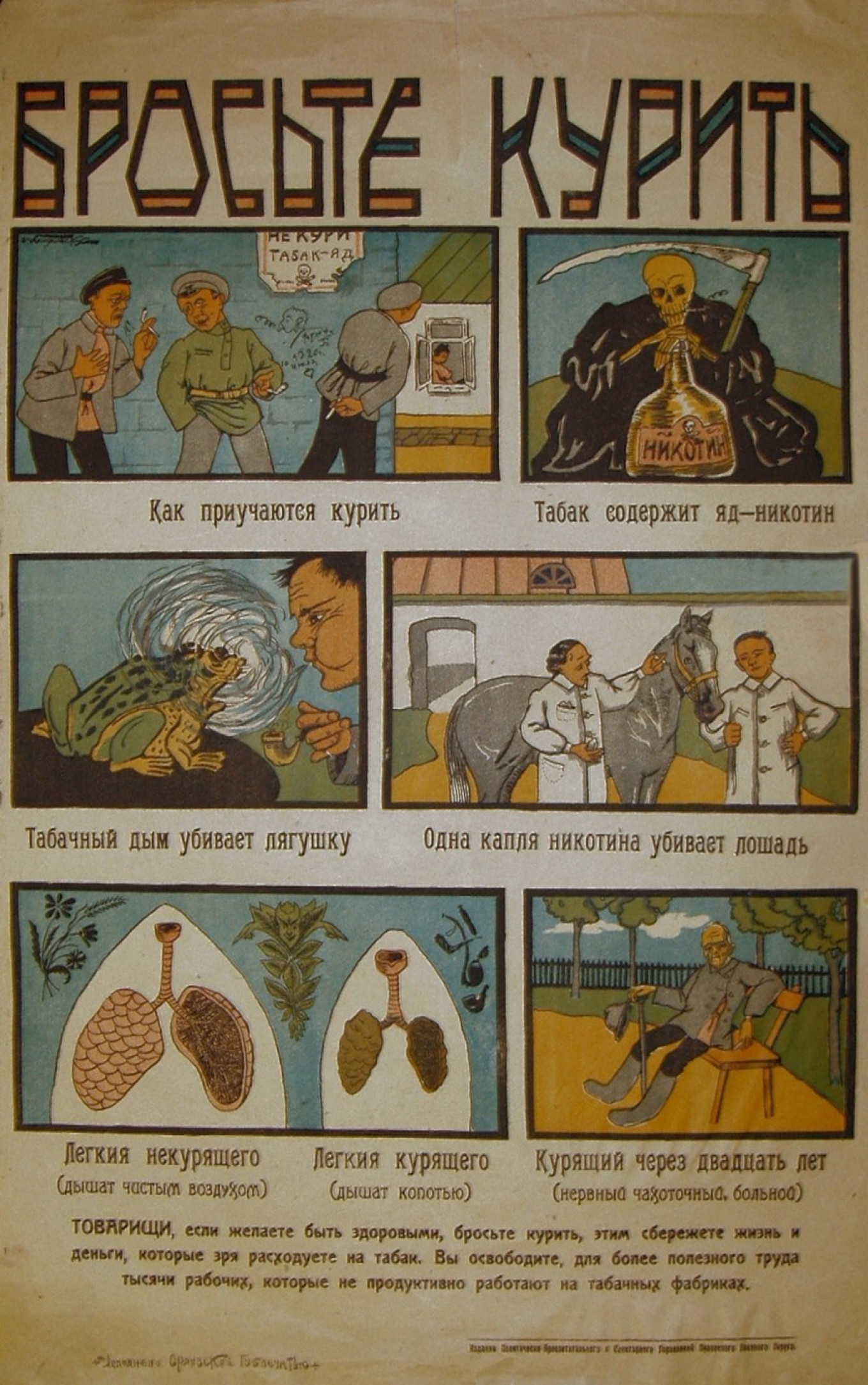

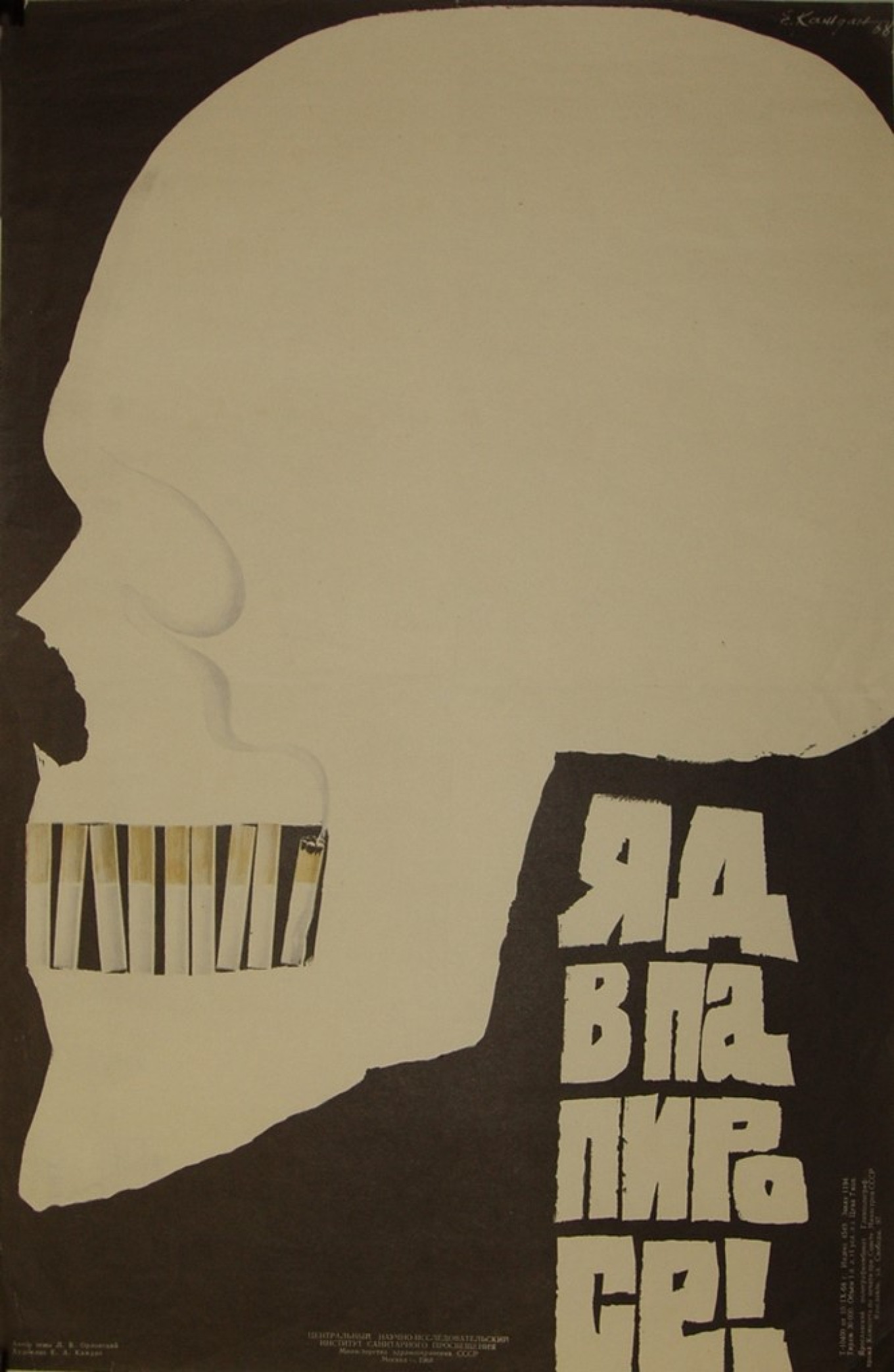

But in the late Soviet period, Starks notes, people disappeared from ads, which were now against cigarettes: “Many Soviet anti-tobacco posters featured smoking, rather than smokers. Disembodied hearts, skulls, or lungs mingled with featureless, usually masculine, silhouettes or dead seen only through their funereal trappings.”

Regardless of ads, “Soviet smokers constructed their own meanings for tobacco,” Starks writes. “Display of a cigarette — in its smoking, its presentation, its packaging, its sharing, its gifting — all held power as a signifier of status or aspirational status, gender, and even locality. With every puff, smokers exhaled a complex language articulated through type of smoke, place of production, and scarcity of brand. Display of western fashion, including cigarettes, became an important sign of cultural sophistication in the postwar Soviet Union.”

The smoking lore is, on occasion, even seductive. When the first supply of American tobacco arrives in Moscow for the Soyuz-Apollo cigarettes, Starks lets the head of the Soviet factory describe the scene. “We would open the box, and there was the beautiful golden color, with a dark shimmer. It was tobacco worked with a special sauce and releasing a sumptuous scent. It was simply fantastic.”

But that is all in the past. In the 21st century, smoking is finally on the wane. “If in 2009 more than 60% of Russian males smoked, as of 2016 that number was about 50%, according to data from WHO’s Global Adult Tobacco Survey,” Starks writes.

“The spaces and scentscapes of today’s Russia have been transformed with these restrictions and impositions of no-smoking spaces. Stairwells and entryways no longer reek of tobacco. Tobacco butts have diminished. The smell of tobacco on people’s clothing in buildings is not nearly as sensible. It is a new world.”

Cigarettes and Soviets: Smoking in the USSR

From Chapter One

Attacked: Commissar Semashko and Tobacco Prohibition

After the February Revolution of 1917, Vladimir Il’ich Lenin and nearly three dozen other displaced radicals began a trek across war-torn Europe. They sped back to Russia to agitate for even greater change, barreling through hostile territories in a special train car where real German guards monitored the chalk lines that denoted their space of fictive Russian soil. But more than suspicious glances and phantom borders divided the travelers. As the revolutionaries passed through the fields of one war, Lenin fired the first salvo in a battle that few had anticipated—an attack on tobacco.

It was no secret that Lenin abhorred tobacco, but many of his colleagues embraced the habit. Surrounded by puffers, Lenin imposed no-smoking zones for their steam-powered isle of Russian territory—tobacco use would be allowed only in the bathrooms. For the thirty-some activists pressed together for days of travel, this sanitary authoritarianism nurtured the seeds of discontent. Soon enough the bathrooms became clogged with smokers, lines snaked down the corridors, and bickering erupted. Lenin stepped in, “with a sigh,” issuing bathroom tickets for two types of clients—smokers and users. For every three conventional uses, he issued one smoking ticket, rationing tobacco time and smoothing over the difficulties he had created.

A queue persisted, but things got back to a more normal state of affairs as discontent turned to discussion of absent comrades—and what they would say to Lenin’s tobacco tyranny. Karl Radek joked, “It’s a pity that Comrade Bukharin isn’t with us.” Others agreed that Nikolai Bukharin could surely have enlightened the waiting group on the placement of tobacco on the varying “levels of human necessity,” because he was an expert in the Marxian-value theories of the Austrian economist Eugen von Bohm-Bawerk. Lenin’s thunderous return became the subject of many books, yet no one seems to have recorded if the revolutionaries finally settled the necessity of tobacco.

After his return to Petrograd, through the fall of the Provisional Government, and following the success of the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin’s disgust for tobacco did not wane. The revolutionary Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich joked of Lenin, “He could not stand the smoke . . . Wherever he was—by himself in the office, at home, at a meeting, or a discussion, even as a guest—he energetically protested smoking . . . hanging signs everywhere saying, ‘here it is forbidden to smoke,’ ‘please don’t smoke’ . . . [he] resented when smokers did not follow these requests and . . . told them that if they themselves could not stop . . . why must others put up with and breathe this disgusting, stupefying-to-consciousness poison.” At the meetings of the Soviet of People’s Commissars, Lenin exiled the smokers to the fireplace, forcing them to blow their smoke up the chimney and mocking them as “charred cockroaches.”

Although Lenin’s smoking prohibitions tended toward securing his personal comfort, he found an ally for a broader fight against tobacco in Nikolai Aleksandrovich Semashko. Semashko was the leader of the newly created Commissariat for Public Health. As the leader of the world’s first national health administration pledged to universal, unified, prophylactic care, Semashko placed the Soviets at the forefront of twentieth-century socialized medicine and, importantly for this story, smoking cessation. Semashko waged a war against tobacco unprecedented for its intended scope and exceptional in range, making the Soviets the first country in the world, in 1920, to entertain a national health program to curtail tobacco production, sales, imports, exports, and use with the goal of eventually stamping out tobacco. Semashko did not achieve his full utopian ideal. Political and economic regulations languished, but the Soviets established the earliest national anti-tobacco campaigns and funded the first public cessation clinics.

Despite this early start, the animosity of the architect of the revolution, and the support of the leader of the first national health service in the world, tobacco remained integral to the Soviet experience and grew in use. By the 1960s–1970s, Soviet medical authorities estimated smoking rates of 45.0 to 56.9 percent among men and 26.3 to 49.1 percent among women. Despite recent successes, the numbers caught in dependency and suffering are still high. In 2020, 50.9 percent of Russian men and 14.3 percent of women used tobacco, most in cigarettes. For comparison, smoking rates in the United States crested in 1965 at 52 percent of males and 34 percent of females and currently hover around 15 and 13 percent, respectively. Considering that regular tobacco use kills half (or more) of its users with a smoking-related illness, it should not be surprising to learn of the nearly 329,000 tobacco-related deaths in Russia in 2020 or overall about 30 percent of male and 6 percent of female deaths.

Lenin and Semashko’s attention to tobacco reflected not a quixotic fight against an imaginary enemy but a reaction to its prevalence in revolutionary Russia. Despite an initial resistance in the 1600s, Russians had strongly taken to tobacco by the nineteenth century. In 1898, the anti-tobacco author Dr. A. I. Il’inskii claimed that in Russia, a country infamous for its prodigious drinking, “the number of smokers is ten to twenty times greater than the number of people in alcoholic excess.” Although other types of tobacco use were available in Russia and then the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, by far the most common mode of intake was the unique Russian cigarette—the papirosa (singular -a; plural -y). The hollow cardboard tube affixed to a tissue paper- wrapped cartridge of leaf accounted for almost half of all processed tobacco in Russia by 1914; by 1922 the number was 80 percent. For comparison, on the eve of World War I only 7 percent of tobacco in the US went into cigarettes. Most Russian tobacco went to papirosy or loose tobacco for self-rolled smokes, and most Russian males smoked. Official consumption statistics, based on taxes, assumed 143 papirosy per person per year, but observers estimated much higher usage. Industry analysts claimed that a pack a day (about twenty smokes) was standard for almost every Russian male. The use of tobacco stretched across the empire, through its social fabric, and across its cultural divides, a democratic dependency that still allowed differentiation of status with brands, accessories, and styles of consumption. The more than one thousand Russian papirosy brands recorded by 1913 implied a market of diversity and size. Even women smoked in large enough numbers to merit custom marketing, specialized brands, and exquisite Fabergé accessories. It would be years, decades in some cases, for similarly mass use of cigarettes to develop in other markets.

Not only did Russians consume tobacco in large numbers and in a unique form, most lower-class users, the vast majority, smoked a singular type of tobacco called makhorka. Makhorka (Nicotiana rustica) is a nicotine-laden, highly fragrant tobacco varietal smoked, loose and self-rolled, by about two-thirds of Russians at the time of World War I. For the peasantry easily grown, worked, and smoked makhorka offered a cheap, untaxed, and untraced way to smoke. In the city, the use of aromatic, rough makhorka differentiated class, as makhorka was cheaper than the oriental/Turkish leaf (Nicotiana tabacum) preferred by well-heeled smokers. American-style bright leaf appeared rarely.

These two conditions exceptional to late imperial Russia—the large portion of tobacco smoked rather than snuffed, piped, or chewed and the availability of nicotine-heavy makhorka—made the Russian smoker revolutionary in another way. They created the possibility for more powerful tobacco dependency. Inhaled tobacco, as with cigarettes rather than pipes, quickly impacts the smoker. Dragged into the lungs, inhaled smoke delivers over 90 percent of the nicotine to the blood in less than thirty seconds, giving a quicker fix and increasing the possibility of dependency. Not only did Russians take to a more addictive means of tobacco use, but the tobacco smoked by the majority was incredibly strong. Makhorka contains nearly twice the nicotine of other tobaccos, and contemporary accounts all point to it being inhaled, despite the harsh experience this must have imparted. These two factors are likely to have pulled Russian, and then Soviet smokers, into a quicker, more intense, dependency earlier than those in other tobacco markets.

Whether the smokes were grown and worked at home, then self-rolled into “goat legs,” or factory-rolled papirosy bought from a street seller, a tobacco haze enveloped revolutionary Russia, flavoring every aspect of life. Smoked tobacco, especially from makhorka, produced an almost palpable stench, and in the close confines of the city, the smell of smoke impacted bystanders and the diaphanous tendrils from papirosy showed visibly from afar. After use, smoking marked bodies with stale breath, yellowed teeth, stained fingers, musty hair, and burned and foul-smelling clothes. The smell from cheap makhorka or more dear oriental differentiated class and pretentions. Smoke anchored the “scentscapes” of Russian cities and homes delineating spaces of respectability, danger, work, and leisure with either odor or stench according to personal predilection. The detritus of tobacco—musty spaces, ubiquitous butts, crumbs, and ash—blanketed streets and homes. When Russia experienced its liberal revolution in February 1917, followed by the Bolshevik Revolution in October of the same year, the politics changed, but every rally reeked of smoke. Spent papirosy and crushed packs littered the floors and tables of the numerous, endless meetings. When the journalist John Reed described the postrevolutionary gathering of the soviet in Petrograd, not just Lenin and Trotsky took over the stage but so too did the rank miasma: “There was no heat in the hall but the stifling heat of unwashed human bodies. A foul blue cloud of cigarette smoke rose from the mass and hung in the thick air.” The smell of revolution was tobacco, its sensibility smoke.

This early start made smoking more noticeable and socially accepted and expected earlier, but the reasons and ways that the Soviets opposed tobacco also differed from those of the west. The Bolshevik seizure of power created opportunities for the maintenance of public health, even as heavy state interference in the production and sale of goods became policy. Connections to lung cancer or addiction were years in the future. Instead, Semashko’s and Lenin’s animosity to tobacco stemmed from the mass imposition of its smell and an opinion among some revolutionary-era doctors that nicotine was a poison that attacked the nervous system. In addition to viewing the danger of smoking differently, Soviet medical authorities held unique attitudes toward public health, had a singular set of professional conditions in medicine, embraced therapeutic techniques born of their native reflexology, and expressed concerns over a contextually specific, perceived decline in the population’s health and virility. In the decades that followed the revolution, the Soviets forged innovative cessation techniques dependent on social interventions and chemical therapies and penned inventive arguments regarding the social costs of smoking and the dangers of secondhand smoke.

Despite this push for cessation from some government actors, others supported tobacco production, use, and export. This was not quite the disconnect that it initially appears. On the one hand, not all were convinced tobacco was dangerous, and none considered it addictive like opium or alcohol. On the other hand, many thought smoking would cease on its own. Semashko tied smoking (and drinking) to capitalism and believed that revolution would defeat tobacco as social conditions eased and cultural levels rose. Representatives of industry and trade argued that for the moment, tobacco had to be produced and pursued heightened output to counter black marketing and public anger over low supply. The calculus, established early, maintained for years. Over the decades, state planners centered, celebrated, and even sacrificed for tobacco, and medical figures proved horribly wrong about smoking’s eventual demise. By the end of the twentieth century the newly independent Russian state would be home to one of the highest smoking populations in the world, with horrific consequences for popular, especially male, health.

Excerpted from “Cigarettes and Soviets. Smoking in the USSR,” written by Tricia Starks and published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2022 by Cornell University. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed to ease reading. For more information about the author and this book, see the publisher’s site here.

“Cigarettes and Soviets. Smoking in the USSR” has been shortlisted for this year’s Pushkin House Book Prize, which will be awarded on June 15 in London. Tickets for the ceremony are available here.