Victoria Lomasko is an artist, journalist and writer who has combined her talents to create a new medium. Last year in an interview with The Moscow Times, she explained that she doesn’t work in the genre of “documentary comics or graphic novellas, but in the genre of graphic reporting. It is a matter of principle for me not to draw at home from a photo or sketch, but to immediately make a finished drawing on site.”

Her graphic reports were gathered into a book called “Other Russias” (published in English translation by Thomas Campbell) that was awarded a special commendation by the Pushkin House Book Prize jury in 2018.

Born in Serpukhov, Lomasko graduated from the Moscow State University of Printing Arts with a specialty in in graphic art and book design. In addition to her own work, which harkens back to the Russian traditions of reportage drawing during wars and in the Gulag, she conducts lectures and classes on graphic reporting and has collaborated with many mass media and human rights organizations. Her work has been exhibited extensively in Russia and abroad, and she is the co-curator of two projects: Our Courtroom Drawings (with Zlata Ponirovska) and Feminist Pencil (with Nadya Plungian).

The Moscow Times caught up with Lomasko after seeing her new work for the Creative Time Comics, a project of the Creative Times public arts organization, based in New York City. We asked her about her graphic report on the April Constitution vote in Russia and her thoughts and images of events in Belarus.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

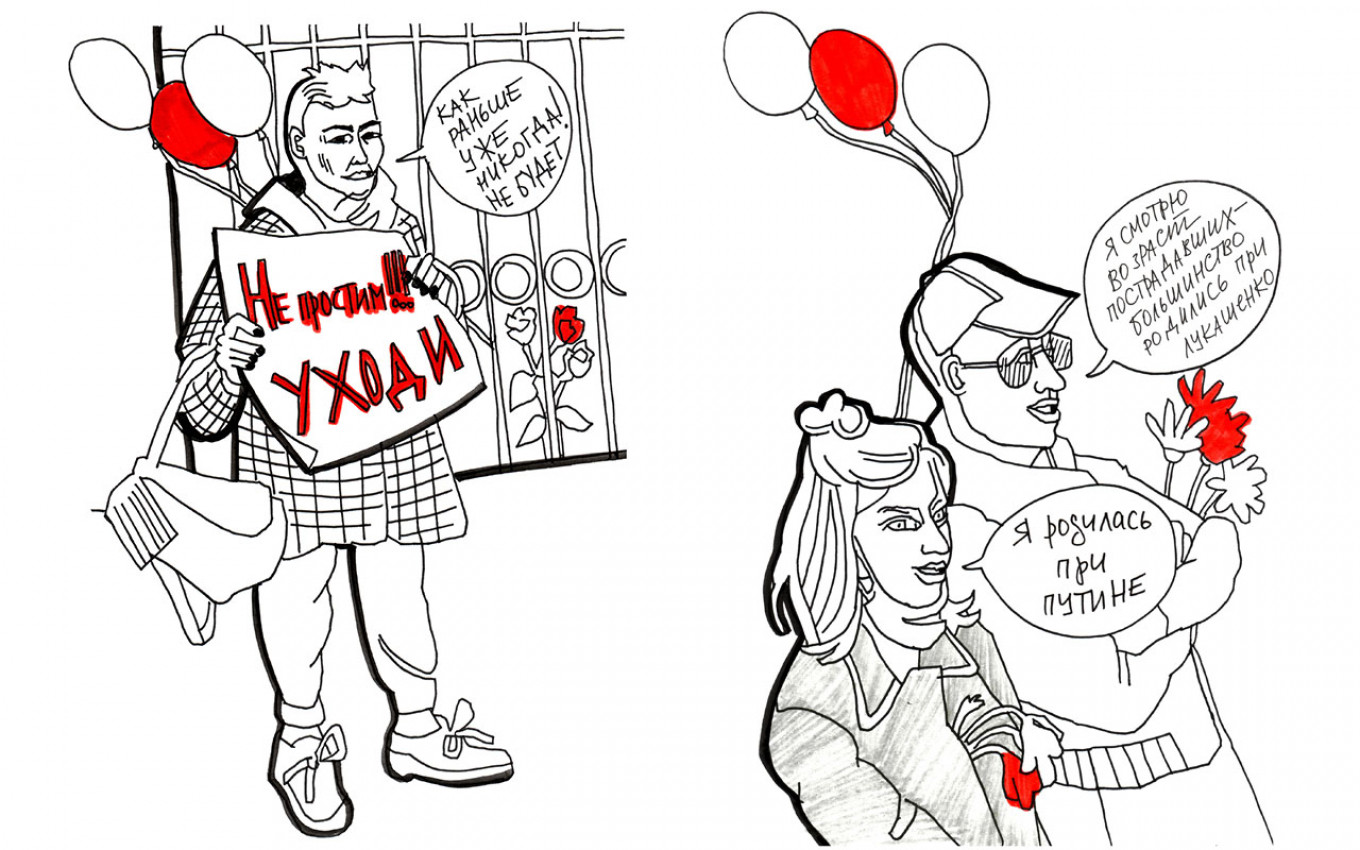

Are you following events in Belarus? Have you captured what is happening there on paper?

Of course, I follow the events while worrying and admiring the protesters. I haven’t drawn about the situation in Belarus, because that would be paraphrasing the existing media’s materials.

But [last] Saturday, feminists in Moscow organized an amazing action called “Viva Belarus: the chain of solidarity.” Girls and women in white with bouquets of white and red flowers, the colors of the former Belarusian flag and the colors of the Belarusian opposition, formed a long, long line opposite the Embassy, holding a long white ribbon in their hands. They were mostly very young girls, looking bright with colored hair, unusual haircuts, piercings and tattoos, in clothes with alternative slogans and shoes. They were all cute and friendly.

For me, what’s happening is a war of generations. The new generation has nothing to do with old dictators, but old people who want to stay in power forever, continue to impose this regime.

Many drivers passing by the embassy played Victor Tsoi’s cult song “We Are Waiting for Changes” as a sign of support. I remembered listening to this song back in my youth, expecting something new to replace the dull Soviet routine. I really hope that this time the change will happen finally and irrevocably.

Could you talk a bit about how you work?

At the beginning, I find topics that are not just interesting for me, but also suitable to research and explore. I don’t want to express my opinion in writing and drawings based on other media materials or photos from the Internet. For me, the “theme” is a question, the answer to which will be given by reality itself; I aspire to be a participant in the events. Life gives us such scripts and images that it is impossible just to imagine them by ourselves.

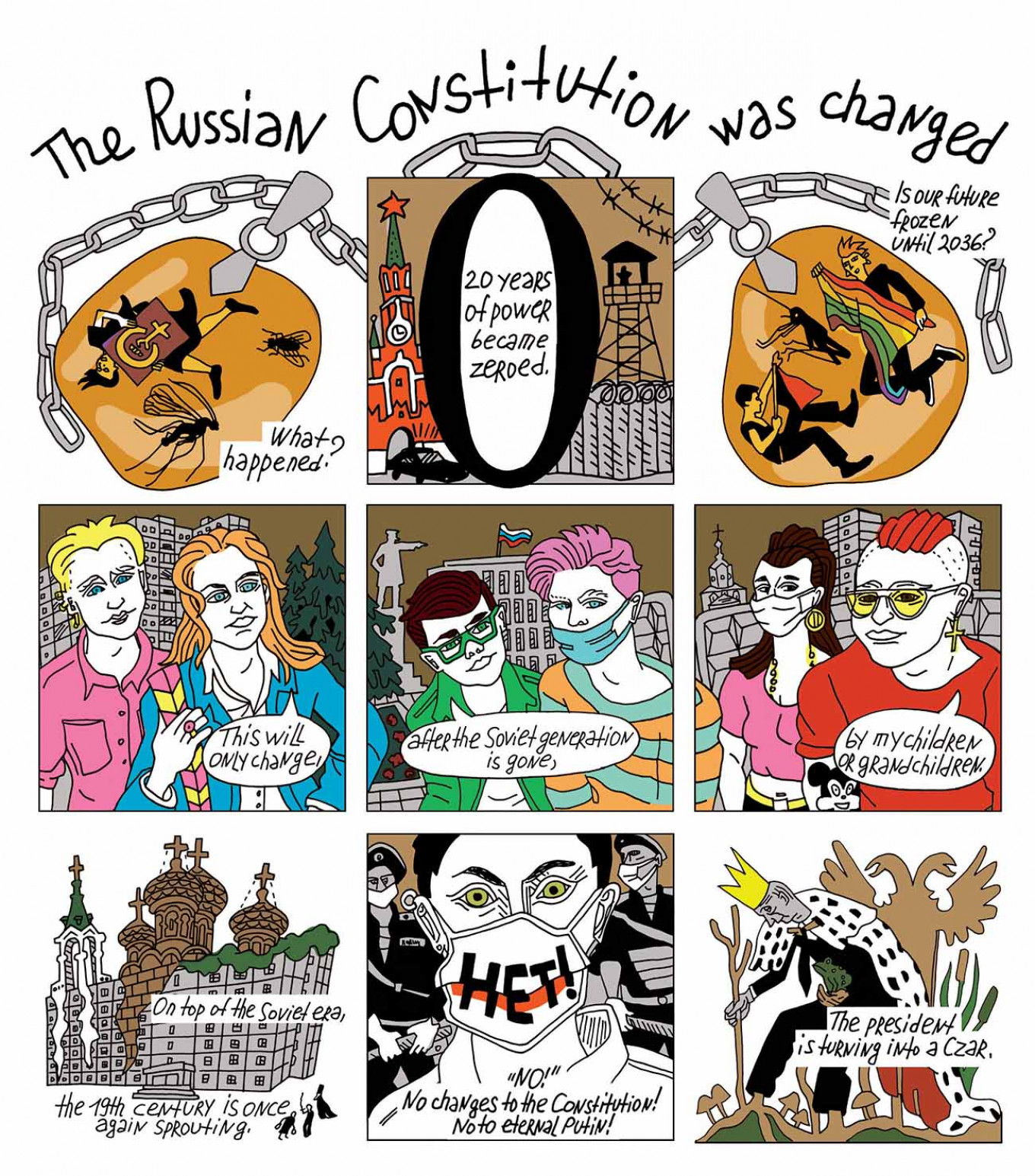

Why did you decide to depict the vote on the Constitution?

I was sure that voting to amend the Constitution of the Russian Federation was a very important topic, but I had no idea what I would see at the voting sites. I was surprised at how many young people came to vote — it is not typical for Russia, usually only pensioners come. I also noticed that they all gave me the same answer in different words — ‘the Soviet past must go away with Putin.’ Around these answers, I created a composition and combined it with other symbolic elements.

In this work, life is frozen in amber. But many of your people are very active and brightly colored. Could you talk about this process in Russia?

In the comic “The Russian Constitution Was Changed,” depicted are young people who get information from the Internet and want to look like their peers in other metropolitan areas. To some extent, it’s a protest — to look fashionable against the background of the musty regime. I remember the day we were told at school that the Soviet Union had collapsed and that we did not have to wear pioneer ties anymore. We started tearing them up right away, and soon everyone changed into jeans and bright leggings.

Many Russian people who want to not only look alternative, but also to act freely and independently, quickly burn out or leave Russia.

How do you work in this half-frozen, half-free environment? Do you work differently in other places?

The Soviet era is not finished completely. Like in the past, the authorities are confronting Russia and the rest of the world that is supposedly hostile to us. Also, the government still controls disenfranchised citizens and destroys any social activity. On the other hand, the ruling elite dislikes communist ideas about economic equality. This is why they took their current mentality from the 19th century the pre-revolutionary ideology of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality,” which now sounds like “Eternal Putin, Russian Orthodox Church and Nationalism.”

I feel that I’m living in the 21st century only when I leave Russia, and once I am back in the country it feels as if I have returned to my Soviet childhood. I feel this especially during this time of pandemic, when all the borders are closed. Quite often, I feel furious that the government steals my life, that the professional circles are ruined, and we are not part of the international scene anymore. At other times, I think I am in my place. It is a big challenge to describe from the inside what is going on in this huge and strange country.

What is the significance of the vote for Russia?

The rush to change the Constitution during the pandemic so that Putin can stay in power until 2036 is a historic event. At the same time, it took place without any public reaction, except for very small rallies. Every summer most Muscovites go to their summer houses or cottages, and this year, especially because of the pandemic, everyone who could, escaped from the city. It was possible to vote online, but it’s not the same as coming to a voting site and finding a crowd of opposition as it was in the presidential elections in 2012.

For me, this vote is an important chapter in our history that began in 2012 when thousands of people rallied in Moscow for fair elections, with Putin once again becoming president, repressions and political trials, the war in Ukraine, widespread censorship and the adoption of new laws.

One day, this story will end and something new will at last begin.