At the end of 2020 just before all museums were closed in Moscow to contain the second wave of the coronavirus, the Museum of Moscow opened “100 Years Old: VKHUTEMAS, School of the Avant-Garde.” Lauded as one of the most important cultural events in the capital, it immediately had to close until a few weeks ago.

The mouthful of an abbreviation VKHUTEMAS stands for the Higher Art and Technology Studios, educational institutions opened in several cities of Soviet Russia soon after the 1917 Revolution. They are often called the Soviet version of the German Bauhaus. From 1920 to 1927, the Moscow VKHUTEMAS had on staff some of the greatest avant-garde artists, architects, designers, and sculptors teaching a new generation of talented young would-be artists and builders. Among the teachers were Alexander Deineka, Vladimir Favorsky, Vladimir Tatlin, Pytor Konchalovsky, Vera Mukhina, Vasily Kandinsky, and the Vesnin brothers.

For the exhibition, a group of young and enthusiastic curators at the Museum of Moscow uncovered an enormous cache of Russian and Soviet art that had been considered lost forever. For the first time it displays in one place works from various media that had been exhibited separately in the past or only in part — or, as with the case of architectural plans — never exhibited at all. It also displays graphics and paintings from private collections and descendants of VKHUTEMAS graduates.

As Zemfira Tregulova, director of the State Tretyakov Gallery, said at the opening of the exhibition: “If the curators of the Museum of Moscow had not been so brave and willing to take risks, the show would not have taken place, since it was extraordinarily difficult to organize the show during the first quarantine. This show,” she said, “lets us go back in time a century to see what every scholar and lover of art should know.”

The idea of the exhibition — showing the entire legacy of VKHUTEMAS in one show — was proposed by a professor at the Stroganov Institute, Alexander Lavrentiev, who is the grandson of avant-garde icon Alexander Rodchenko.

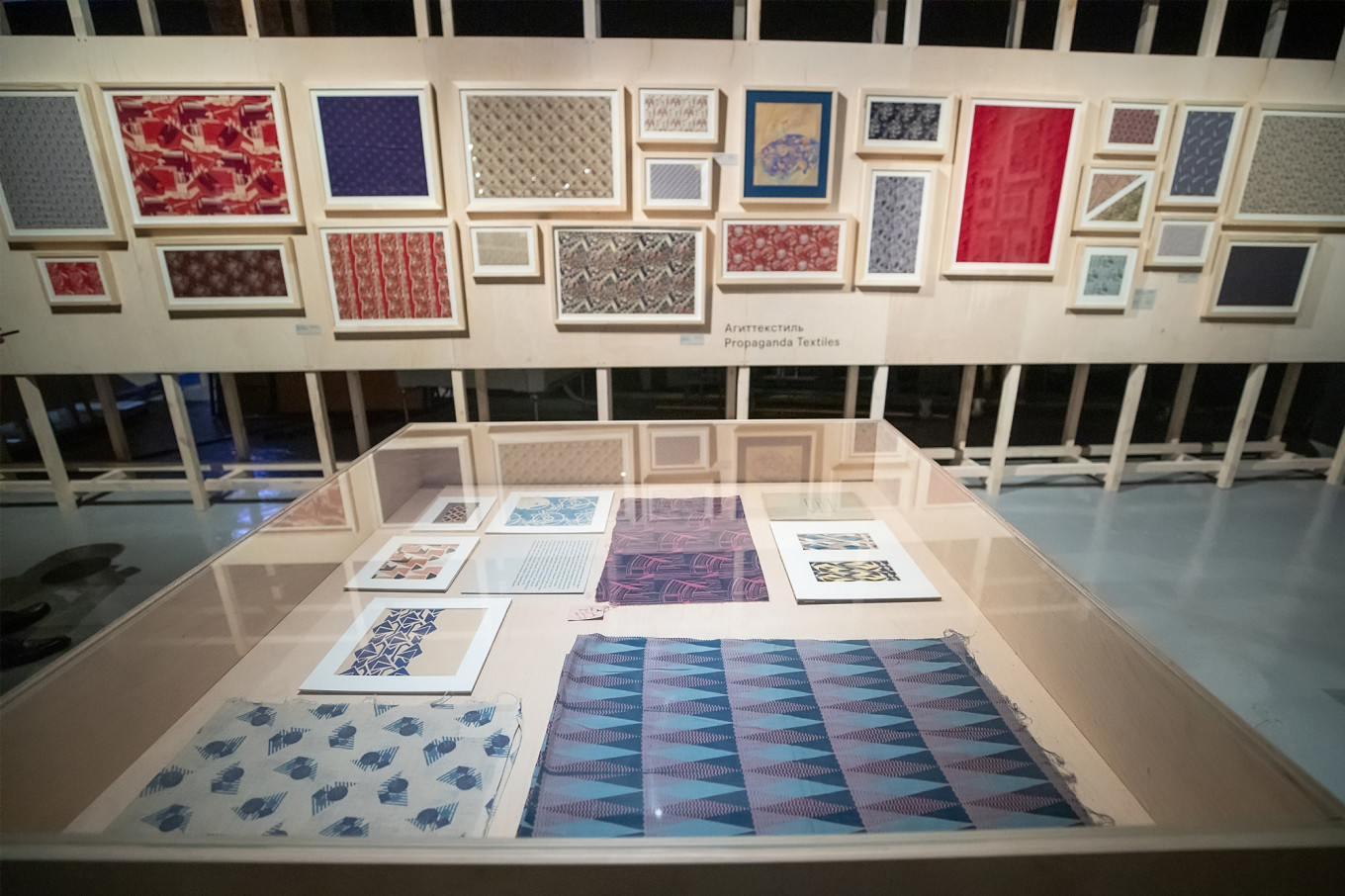

The exhibition has on display paintings, graphics, sculptures, architectural models, porcelain, textiles, and furniture all created by the VKHUTEMAS students. VKHUTEMAS was founded in the years immediately after the Revolution to produce propaganda and usher in the “new life.” They were inventing a new world, as seen in the tower-figure “The World Belongs to Us” that VKHUTEMAS students built in the 1920s, recreated for the show in metal by Nadezhda Plungyan, curator of the painting section of the exhibition.

VKHUTEMAS graduate Tatiana Mavrina, a wonderful painter with a brilliant sense of color, called the school “the fantastic institute.” That can be seen in the show, which has gathered works from 12 institutes all over Russia that became, in one way or another, the descendants of VKHUTEMAS.

VKHUTEMAS was renamed VKHUTEIN (Higher Art and Technology Institute) in 1927. The school survived until 1930 when socialist realism became the dominant artistic ideology and it fell victim to the campaign against formalism. The organizers stressed at the opening that many of the works had been simply destroyed by students and teachers of VKHUTEMAS in order to survive during the Stalinist repressions. Some artists, like Gustav Klutsis and Alexander Drevin, were executed in 1938. Vladimir Tatlin was effectively banished from artistic life, and Vladimir Favorsky was fired from his job for formalism.

As Alexandra Selivanova, the main curator said, the organizers wanted to show the process of creation, not the final result; to put on display creativity, not masterpieces. They wanted to share with viewers works that had been languishing in dangerous oblivion for decades without the necessary conditions for safekeeping.

In her introduction to the show Selivanova wrote, “the radical innovation that distinguished VKHUTEMAS from all the previous art schools was the required course for all students enrolled in the one- or two-year general program. This required subject gave all the students a primer of art and design: color, graphics, composition and work with three-dimensional forms and space. Together these disciplines were called the propaedeutical course (introductory study). The idea for this course in arts education came out of the radical avant-garde trends of 1919 and 1920.”

The curator of the graphics section told The Moscow Times that in choosing artists the organizers limited themselves to artists who were least known and had been — in his words — “thrown overboard.” That’s why works by VKHUTEMAS stars such as Alexander Deineka, Yuri Pimenov, Kukryniksy or the founder of the Puppet Theater, Sergei Obraztsov are not exhibited here. One of these carefully curated works in the graphics section is the “Metropolitan” poster of 1927 with elegant red-capped conductor and conductress.

Much of the exhibition is dedicated to the production departments, each in its own hall: printing, textile, ceramics, woodworking and metalworking. This is where visitors can learn how the VKHUTEMAS printing fonts were developed, about Favorsky’s school and his quest for a new kind of book, how textile designers studied new technologies and how ceramics became a medium for distributing propaganda. On display are furniture and the lighting fixtures that are precursors of the forms we use today.

The final section of the exhibition shows how the legacy of VKHUTEMAS was transferred to other higher arts institutions, in particular, the Moscow Architecture Institute, the Stroganov Industrial Arts Academy, the Printing Institute and Textile Institute. “We all came out of VKHUTEMAS,” said Yekaterina Khokhlogorskaya, director of the Higher School of Print and Media Industry at the Moscow Printing University. An entire hall on the second floor displays works created by the students of that school who base their design objects and books on the legacy of VKHUTEMAS.

Visitors can get a special brochure with Moscow addresses connected in some way with the lives, work and projects of VKHUTEMAS students and students. For example, it shows the apartments of Alexander Deineka and Moisei Ginzburg in the famous “ship house” newly renovated on Novinsky Bulvar; the apartments of El Lisitsky, the Vesnin brothers, Vera Mukhina, Alexander Tyshler, Vladimir Favorsky, Solomon Telingater, and the VKHUTEMAS classrooms on Rozhdestvensky Bulvar.

The exhibition will run until April 11. For those unable to see it live, there is a rich online site here.